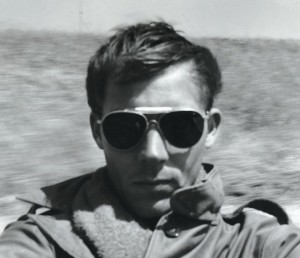

The road trip west from Colorado to California was miserable. The young writer and his new wife rattled over two-lane blacktop on a 1,100-mile journey, through “rotten snow” and baking deserts, driving an old Rambler pulling a trailer. He had little money. She was eight months pregnant. And when they finally pulled into the redneck hamlet of Glen Ellen, the owner of the house they had arranged to rent told them, bluntly, that it was no longer available.

Hunter S. Thompson had arrived in Sonoma County.

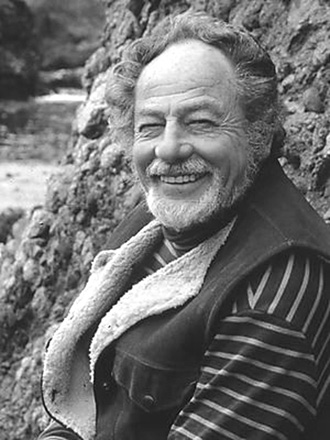

In early February 1964, Thompson was not yet the literary bottle rocket whose freewheeling “gonzo” style of reporting and writing in books including “Hell’s Angels” and “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas” would help change modern journalism. He was struggling, broke, and left his home in Woody Creek, Colo., with his wife, Sandy, to further his career as a magazine reporter.

San Francisco was just 50 miles from Glen Ellen, and he planned to earn money writing articles on the American West for The National Reporter and National Observer. The Berkeley Free Speech Movement was in its early days, the Republican National Convention was coming to San Francisco that summer, and the area was buzzing with colorful ideas and subjects. “There’s too much fresh stuff out here,” he wrote. “I am near the action or at least near enough.”

As for his inauspicious arrival in Glen Ellen, “I arrived pulling my trailer and was denied entrance to the house I was planning to live in,” Thompson recalled. “The fellow had changed his mind.”

The couple found another place nearby, a small ranch house at 9400 Bennett Valley Road. It wasn’t much, but it was home. “I live in a sort of Okie shack, paying a savage rent, and spend most of my day in a deep ugly funk, plotting vengeance,” he wrote to a friend.

Today, the cozy town of Glen Ellen — the downtown has two bends in the road, a small bridge, upscale restaurants and an art gallery — is a quaint gathering spot for visitors to world-class wineries and Jack London State Park. In 1964, it was very different. Gene McGarr, a hard-drinking visitor from the Bronx, described Glen Ellen as “a rural slum.” Everywhere were horses, cows, chickens and old shacks with broken-down trucks tangled in tall grass. The place reeked of manure. Thompson called his new home “the Brazil of America, the land of cheap wine and the 10-cent cantaloupe.” Glen Ellen, he noted forlornly, was merely “Tulsa with a view.”

The Thompsons slept on a mattress and box springs on the floor of their place, and scoured flea markets and secondhand stores for furnishings. He made a desk out of an old door. He called his new home Owl House, perhaps in tribute to Jack London’s Wolf House, whose burned-out ruins were just a few miles away.

On March 24, Sandy gave birth to Juan Fitzgerald Thompson, at Santa Rosa Memorial Hospital. The boy’s name reflected his father’s love for the writer F. Scott Fitzgerald and recently slain President John Fitzgerald Kennedy. Thompson dashed off a letter to his boyhood friend, Paul Semonin, with a mix of personal excitement and professional trepidation. It said: “I have a son named Juan. Ten days old. Not a cent in the house and no cents coming in. I am seriously considering work as a laborer. … I am deep in the grips of a professional collapse that worries me to the extent that I cannot do any work to cure it.”

Thompson’s residency in Sonoma County was a period of hard work and intense self-doubt. A year before, he had been a jaunty journalist, reporting from Puerto Rico and South America, finding his voice as a writer. He stayed up late, drinking rum cocktails and loudly debating others about politics. He was a drifter, young and on the road, and his world was filled with adventure, romance and opportunity.

In 1964, life was quite different. Now Thompson was a man with responsibilities. He was in a strange place with a young wife and new baby, a dying car, a skittish Doberman named Agar and no cash. “It is now a year since I got back from South America, my wallet full of money and my future full of fat leads,” he wrote to Semonin in late April. “But the year has been a bust; for some reason I can’t speak the language here. I am not with it. For the past two months I have been in a black bog of depression, fathering a son, living among people more vicious than I ever thought existed, and bouncing from one midnight to the next in a blaze of stupid drunkenness.”

Thompson was about to turn 27, a date by which time he had always figured he’d be dead.

As a freelancer, Thompson hustled for assignments. For the National Observer, which paid him about $200 an article, he often penned book reviews and lightweight color pieces. “The Observer is decent, but I often wonder about their motives,” he wrote. “I detect a trend in their acceptance of frothy pieces and disinterest in meaty ones.” Thompson reported on the waning beatnik scene in San Francisco’s North Beach neighborhood, as well as an awakening student protest movement in Montana, a Scottish gathering and games in Santa Rosa, and even a piece about Marlon Brando’s futile attempt to help local Indians regain fishing rights in Olympia, Wash.

He traveled to Ketchum, Idaho, to investigate the reasons for Ernest Hemingway’s suicide there three years earlier. Like many writers of his generation, Thompson loved Hemingway; he would sometimes retype “The Sun Also Rises” and “A Farewell to Arms,” not changing a word, in order to understand the rhythm of Hemingway’s language. The resulting “What Lured Hemingway to Ketchum?” story for the Observer was one of his finest pieces.

Thompson’s analysis of Hemingway’s waning powers in his final years shows signs of self-reflection: “The function of art is to bring order out of chaos, a tall order when the chaos is static and a superhuman task when chaos is multiplying.” Before leaving Ketchum, Thompson stole a pair of elk antlers hanging above the front door of Hemingway’s cabin.

Despite the range of assignments, Hunter felt isolated in Glen Ellen. “I am in the same condition here as in Woody Creek, only in less colorful and pleasant surroundings,” he wrote to novelist William J. Kennedy. “I have no conversations except on chance meetings in San Francisco. Once a month at best. My only hope is to make enough money to get to New York at once and run out my mouth to the detriment of the populace.” He managed to secure an office in the San Francisco bureau of the Wall Street Journal. “I would wander in on off-hours and obviously on drugs and ask for my messages,” Thompson recalled. “They liked me but I was like a bull in the china shop.”

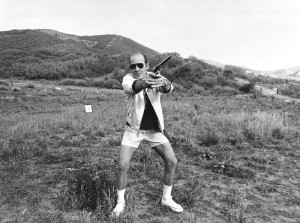

To cure his boredom, after dark he would poach deer in the woods behind Owl House. When Agar flushed the animal out of the brush, Thompson would attempt to bring it down with his .357 Magnum pistol, firing into the dark.

Thompson also began to develop an unconventional and energetic style of writing that mixed fiction with factual reporting, a style he later dubbed “gonzo” journalism. “Fiction is a bridge to the truth that journalism can’t reach,” he wrote to book editor Angus Cameron in 1965. “Facts are lies when they are added up.” Thompson’s approach, which he called “impressionistic journalism,” involved injecting himself as a participant into the events of the narrative. A mad rush of words and images, as well as added metaphoric elements, created a swirl of facts and fiction, deliberately blurred.

It was fresh and groundbreaking, well suited to documenting the hypocritical and degenerate aspects of American society.

Novelist Tom Wolfe described Thompson’s style as “part journalism and part personal memoir admixed with powers of wild invention, and wilder rhetoric inspired by the bizarre exuberance of a young civilization.” Wolfe called Thompson “the century’s greatest comic writer in the English language.”

Four months after arriving in Glen Ellen, however, Thompson was desperate; he even pawned his belongings (including some of his beloved guns) to make rent. Feeling at the end of the road as a journalist, he sent a letter to President Lyndon Johnson (probably facetiously) offering his services as the next governor of American Samoa.

“I have a need for an orderly existence in a pacific place, in order to complete a novel of overwhelming importance to the sanity of this era,” he wrote, on stationery from the Holiday Inn in Pierre, S.D. Two weeks later, White House Special Assistant Larry O’Brien answered, noting that Thompson’s offer would be “given every consideration.” Elated, Thompson went to Brooks Brothers and purchased several white linen suits befitting a future governor. “When can we get with it?” he wrote back to the White House. “I am eager to be off. … Haste will benefit us all.” No more was heard from LBJ’s office.

In August 1964, Republicans descended on San Francisco for the Republican National Convention at the Cow Palace. Barry Goldwater, the ultraconservative senator from Arizona, headed the party’s ticket and made his famous vow to the delegates: “Extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice.” Thompson covered the convention for the National Observer, and recalled feeling afraid that he was the only person in the building not loudly applauding.

While there, Thompson was heard on the telephone brutally swearing at a representative of AT&T, who had threatened to turn off his phone in Glen Ellen for nonpayment of bills. The editors sent Thompson a letter of reprimand: If he was going to represent their paper, he had to get his act together.

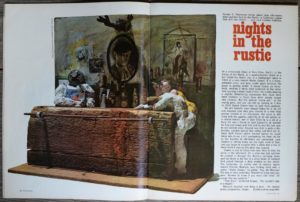

After hours, Thompson began hanging around an old bar called the Rustic Inn in downtown Glen Ellen. Built in 1876, the Rustic was the last of the original 11 bars that once lined Arnold Drive. It was destroyed in a 1974 fire, but for many years the Rustic’s owners did a tidy business by selling the myth that the place was Jack London’s favorite watering hole. To Thompson, the Rustic was a roughneck retreat plying on gullible tourists. Even locals were wary of the place.

Thompson drafted a piece called “The Rustic Inn & Jack London & The Valley of the Moon” and submitted it to several publications. “It’s a pure color job, but a good one,” he clucked to an editor.

“The 1890s atmosphere is badly addled by 1960-style hoodlums who long for trouble,” he wrote. “On most weekend nights the place fills up with one of the sleaziest mobs in all Christendom. Along with the regular handful of pot-bellied frumps and the muscular women who work at the nearby hospital for the mentally retarded is a hard core of out-of-control customers who would tax the hospitality of the most venal innkeeper in the mountains of eastern Kentucky.

“The Rustic, in truth, is the sort of place where people grab you by the arm and say alarming things. The kind of drinking that goes on here would not be out of place in a Bolivian Mining camp, 15,000 feet up in the Andes, where the Indian miners have a life expectancy of twenty-nine years. It would not be out-of-place in Butte, Montana, either, or in most of the bars in east Los Angeles — but none of these places are rustic enough to attract the tourist trade.

“The same sort of brawl that would draw a dozen club-swinging cops to a bar in San Francisco’s Mission District is dismissed with a friendly chuckle in Jack London’s favorite saloon.”

He couldn’t sell the article until three years later, when it was published in the August 1967 issue of Cavalier, a men’s magazine, under the shortened title “Nights at the Rustic.” The owner of the roadhouse, Chester Womack, promptly sued Thompson and Cavalier for $5.5 million. “Never trust a bartender,” Thompson snapped.

In late summer 1964, Thompson invited Bob Geiger, a local orthopedic surgeon and friend, up to the house. A few hours before dawn, the two started shooting gophers on the front lawn. The landlord, who lived next door, was furious and told the Thompsons they had to go.

They moved south to Sonoma to live with Geiger in a small condo he rented, but it was only temporary. By September, Thompson had had his fill of Sonoma County. He wanted to be closer to the action and grabbed a long, narrow apartment on Parnassus Street in San Francisco, near the Haight neighborhood. It was there Thompson wrote “Hell’s Angels,” the book about the infamous California motorcycle gang that launched his career and changed his life. Five years later, he authored his landmark novel, “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas.”

But all that was ahead of him. Shortly before he moved to San Francisco for good, Thompson returned to Sonoma to pack up his remaining gear, loading it into a trailer with the help of Geiger. As the two drove away, the mattress caught the wind and flew out of the trailer, landing in the road. Hunter S. Thompson’s time in Sonoma was over, but his life as a literary icon had just begun.

Authors Note: Hunter S. Thompson himself was a very helpful assistant in this story on the writer’s short residency in Sonoma County. He was a relentless correspondent and, beginning in his teens, made carbon copies of every letter he wrote — to his mother, his Army buddies, his girlfriends, his various agents and editors. The earliest series of those letters are collected in The Proud Highway: Saga of A Desperate Southern Gentleman, 1955-1967. The book includes dozens of pages of his correspondence during his time in Glen Ellen, from February to September 1964. The quotes in this story are chiefly draw from that book as well as Gonzo: The Life of Hunter S. Thompson by Jann S. Wenner and Corey Seymour, which is filled with first-person accounts of those who knew Thompson best. Thompson’s memoir Kingdom of Fear: Loathsome Secrets of a Star-Cross Child in the Final Days of the American Century was also helpful in adding perspective to his Sonoma days. In addition, critical context and backdrop was provided by a number of books, including Outlaw Journalist: The Life and Times of Hunter S. Thompson by William McKeen; Fear and Loathing: The Strange and Terrible Saga of Hunter S. Thompson by Paul Perry; When The Going Gets Weird: The Twisted Life and Times of Hunter S. Thompson by Peter O. Whitmer; and Hunter: The Strange and Savage Life of Hunter S. Thompson by E. Jean Carroll.