There’s a new generation of young farmers battling droughts and aphids, wild pigs and gophers to bring their wholesome produce to the table this harvest season. Toiling in the soil from Geyserville to Petaluma, Sebastopol to Sonoma, this new crop of cultivators has brought growing energy and expertise to the local food movement.

Some of them have access to family land, others work as farm managers, and some lease their plot of earth. They all share a common goal of sustainability for the long-term health of the land.

They are serious about attracting beneficial insects, rotating crops and planting the tastiest heirloom vegetables you’ve never heard of, from Red Burgundy okra to Marina di Chioggia squash.

Picking produce at the peak of freshness in the morning and rushing it to local restaurants and markets with all its flavor intact is really what feeds these farmers’ souls. Then it’s up to us to take those perfectly ripe Padron peppers and nudge them toward nirvana with a splash of olive oil, a flash of heat and a sprinkle of salt.

Meet the new breed of Sonoma farmers

Six Oaks Farm

Farm Manager David Pew, 37, walks through the raised beds at Six Oaks Farm in Geyserville and tests an ear of corn for sweetness.

“It’s an incredibly beautiful place to work,” he said. “This is my office. I can’t complain.”

Pew has a degree in environmental geology from UC Berkeley and studied at the Center for Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems at UC Santa Cruz.

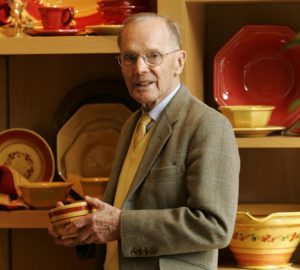

The sustainable farmer was lured to Six Oaks by the long-term vision of its owner, Hal Hinkle.

“Hal has a vision of a ranch that is holistic, with biodiversity and beneficial habitat,” Pew said.

The 2-acre vegetable farm is located at Sei Querce Vineyards, a sprawling ranch in the Alexander Valley dotted with valley oaks and Cabernet Sauvignon vines.

Six Oaks produces everything from Charentais melons to Padron peppers, which are sold to restaurants and at the Healdsburg Farmers Market.

“There is endless nuance and variation from season to season,” Pew said. “I enjoy it immensely.”

Handlebar Farm

Emily Mendell, 31, and Ian Healy, 30, both grew up in the Midwest, amid the towering tassels of corn farms.

The couple went through a few careers, first as park rangers in Alaska, then as educators in Marin County, before deciding to sink their hands into the soil.

With the help of FarmLink, a nonprofit that helps young farmers find land, they leased 2 acres of loamy soil in southwest Sebastopol in 2013 and launched Handlebar Farm.

“I always wanted to run my own business,” said Mendell, who oversees the planting. “I just hadn’t found my passion.”

Healy delivers produce to local restaurants and sells at Santa Rosa’s West End Farmers Market. He also oversees gopher eradication (163 and counting).

The farm received organic certification this spring and grows a wide range of crops, from tender lettuces to sturdy peppers. Like the West End Farmers Market, the couple takes a break for a few months in the winter.

“It’s a good recuperation time,” Healy said. “We go see family and enjoy the negative-30s in the Midwest.”

Foggy River Farm

Emmett and Lynda Hopkins, both 31, have a reputation as community builders as well as farmers. The couple, who met while pursuing five-year master’s degrees at Stanford University, have farmed for seven seasons on 4 acres next to the Russian River, southwest of Healdsburg at what they call Foggy River Farm.

The surrounding ranch was originally planted to hops, then pears and prunes, and finally wine grapes. It’s a microcosm of the region’s history.

Last year, the Hopkins experimented with the endangered Bodega Red potato. This year, they added a purple barley and 12 varieties of heirloom dried beans.

“We’re interested in growing as many different parts of the diet as we can,” said Emmett, who sells at the Healdsburg Farmers Market, the Santa Rosa Original Farmers Market and through Foggy River’s subscription program.

In the past few years, the couple also hatched a new chick, 2-year-old daughter Gillian.

“We’re finally at a point now where she understands rules,” Lynda said. “She can free-range on the farm.”

As a third-generation farmer on his family’s 200-acre ranch, Emmett leases the land for a nominal fee. But that doesn’t protect the farm from disasters. In her blog, Lynda has documented their ongoing war against marauding wild pigs.

Meanwhile, their toddler has helped them reconnect with their original joy. “She can be entertained with mud,” Lynda said, “and sort bean seeds for hours.”

Quarter Acre Farm

Andrea Davis-Cetina, 31, grew up in Maryland watching the surrounding farms disappear under houses. Vowing to make a difference, she studied sustainable agriculture at Hampshire College in Amherst, Mass., then headed west to join the sustainable-food movement in Sonoma.

She got a job as the edible gardener for The General’s Daughter restaurant in Sonoma, then launched Quarter Acre Farm in 2008 in the Two Rock Valley of Petaluma.

The next year, Davis-Cetina leased land closer to home, on East McArthur Street in Sonoma, and started selling her organic produce at the Sonoma Farmers Market. But the low-lying land was under water most of the winter. In 2011, she moved Quarter Acre Farm once again, to a zigzag patch 2 miles south of the Sonoma Plaza.

In 2014, she faced a different challenge. The drought required her to dry-farm without water.

“Normally I grow 40 different crops,” she said. “This year, I’m growing about four (tomatoes, potatoes, tomatillos and dried beans).”

But the feisty, first-generation farmer is determined to persevere as one of the few young farm operators and organic growers in Sonoma Valley.

“It’s tricky,” she said. “You definitely have to come at it with the attitude, ‘I know I can do this.’”

***

Farmer Favorites

David Pew’s Favorite Okra: Red Burgundy

“It likes plenty of heat,” he said. “You need to harvest it every other day, when the pods are young and tender.” Although Southerners like to pickle or fry okra, Pew prefers to cut it into rounds and dry-sauté it in a cast-iron skillet. “It’s really good for Asian stir-fries,” he added.

Ian Healy and Emily Mendell’s favorite pepper: Jimmy Nardello

This long, skinny pepper begins green and ripens to red, with a hook at the end. The Italian frying pepper is sweet and crisp when eaten raw, creamy and soft when fried. “A lot of people like to grill them, to add a smoky flavor,” Healy said. “Emily and I will throw them into a pasta dish.”

Emmett and Lynda Hopkins’ favorite winter squash: Marina di Chioggia

The farm specializes in all kinds of winter squashes, from Sweet Dumpling and Delicata to Jarrahdale and Kabocha. One of the most unique is the Marina di Chioggia, an Italian heirloom that is turban-shaped and deep blue-green outside, with deep yellow-orange flesh. It can be roasted for soups and curries, or baked into a pie. “I like to par-bake them before cutting into them,” Lynda Hopkins said. “It’s traditionally used for ravioli, gnocchi and risotto.”

Andrea Davis-Cetina’s favorite tomato: Japanese Black Trifele

When ripe, Black Trifele grows to the shape and size of a Bartlett pear, with a deep mahogany color and green shoulders. The flavor is spicy and rich, and its silky texture makes it ideal for eating fresh in salads and salsas. “They are so meaty that they work well in cooking, too,” she said. “It performs great in the field, producing a steady harvest even in poor years.”