Franklin D. Roosevelt once said, “When you reach the end of your rope, tie a knot in it and hang on.” He may have been talking about the Great Depression, but that same desperation applies to our pandemic economy. At this point, more than eight months after the outbreak began, even the knot is starting to wear thin.

“It’s like gardening. People love to have a garden, but if you don’t water the garden, the plants will die,” says Andy Weinberger, owner of Readers’ Books in Sonoma. “If you don’t support these stores and boutique-y shops you think so highly of, they’re not gonna be there anymore. You gotta water the garden.”

The easiest thing we can do this holiday season is order from Amazon and never leave our houses. But while we wait for a barrage of boxes to magically land on our front doorstep, we should ask ourselves, why do we live here? Why not Kansas? Or Oklahoma? At least part of it has to do with a sense of community. That sense that we all chose this same spot to put down roots.

“You’re buying something from the source,” says Jennifer Conner, who makes and sells artisanal leather handbags at In the Making in Petaluma. “At the end of the day, I’m not just selling bags. It’s bigger than me, it’s important.”

From a couple finding ways to keep their tiny restaurant open while raising two young children to a septuagenarian who runs a winery all by himself, here’s an inside look at a handful of local businesses holding on to that Rooseveltian knot. While each tells the story of how they’ve weathered the storm so far, what they’re really telling us is how they need our help more than ever.

Tamales Mana

Selling essential foods for essential workers, even after a Covid scare.

In July, when an employee tested positive for Covid-19, owners Manuel Perez and his wife Lucina Cardona thought it might spell the end.

“We wondered if anyone would ever want to eat our tamales again,” Cardona says, snacking on a sweet raisin tamale one afternoon at their storefront and commercial kitchen on Petaluma Hill Road in Santa Rosa, where they make around 1,200 tamales a day. A “God Bless America” sign hangs on the wall beside her.

Over the past 10 years, since Perez started selling the addictive stuffed masa treats in a Food Maxx parking lot and in front of a Grocery Outlet, the couple has cultivated a devoted following. In the beginning, everything was made by hand, including the salsa, in their small apartment off Stony Point Road. Instead of lard, they used soybean oil. As a memento, they still have the original countertop food mixer that Cardona bought thanks to a generous Mervyn’s employee discount.

In an age when many Mexican immigrants send money back to their homeland, Perez and Cardona went in the opposite direction, asking relatives in Mexico to loan them money to buy a new $9,000 cart with permits. It was the biggest risk they’d ever taken.

But after their main cook, who whips up a new batch of tamales at 1 a.m. every morning, tested positive for the virus, the pair had to shut down operations for 14 days — the equivalent of more than 16,000 tamales or $42,000 in sales.

“Fortunately, I had already applied for the PPP loan and it arrived in time to help our employees get through,” Perez says. “But it was still a very scary time for everybody.”

When the quarantine was lifted and no one else tested positive, the restaurant made only half the daily tamale quota to test the waters in that first week back. “We wanted to see if anyone would come,” Cardona says. “When they lined up again, we knew how lucky we were.”

Their tamale cart in the shopping center at the corner of Dutton and Sebastopol roads accounts for about 80% of sales, with the rest coming from takeout orders at the Petaluma Hill Road shop. Workers line up as early at 5:30 a.m. to pick up lunch before heading out, often to fields, vineyards, and construction sites. In a sense, Tamales Maná (“tamales from heaven”) makes essential food to fuel essential workers.

As December approaches, the couple is hoping to recoup some of the money they lost during the quarantine and the early months of COVID when sales were down at least 40% and they had to reduce employee hours. It helps that tamales are such a huge Mexican holiday tradition. Cardona remembers eating her first tamales during holiday celebrations in Mexico City where she grew up. And Perez ate them as a kid, always wrapped in banana leaves, which were plentiful where he lived in Acapulco.

“The holidays are so crazy, and everyone has to have their tamales, that last year we had to add Dec. 23 as a day to pick up tamales, because we could not possibly make any more tamales for Dec. 24,” Perez says. “We are hoping even with the pandemic, this year will be the same.”

Jeremiah’s Photo Corner

Where the owner knows your name — and what kind of film you need.

“I’m a visual person,” says Jeremiah Flynn. He remembers faces like he remembers old, quirky cameras and the photos he took with them. When a regular shows up at his Santa Rosa shop, he says, “I’ll remember, oh this person likes taking photos on road trips or taking photos of their children. This person is looking for black-and-white film or a certain kind of photo paper.”

Open for the past 11 years in the South A Street Arts District, Jeremiah’s Photo Corner has the antique

appeal of a Dickensian curiosity shop. It’s the place to go for refurbished medium-format Hasselblad and Mamiya film cameras and hard-to-find Polaroids. Or film sold from a refrigerator. Or darkroom supplies to develop your own film. “People will show up and say, ‘I’m so-and-so’s mom or boyfriend and they said you would know what I should get them for a birthday present.’ We’re that kind of shop.”

So when the pandemic hit and Flynn was limited to curbside special orders and email queries, all those visual cues disappeared. Sales plummeted at least 80% in the first few months. Instead of walking customers around his packed one-room shop or sending them rifling through boxes labeled “shutter release cables” or “tripod heads,” Flynn spent countless hours “sending email volleys back and forth for a minimal $20 sale.”

To adapt, he bought rolling shelves and set popular supplies closer to the door, where customers can now shop individually while leaning over a baby gate. He started selling more vintage cameras on his Etsy site, noticing an uptick once federal unemployment stimulus checks kicked in. Worried that he couldn’t make rent, much less put food on the table, he immediately applied and received an Economic Injury Disaster Loan (EIDL) for $2,000. And once PPP loans were approved for self-employed business owners, he received a “much-needed” $6,500 boost in August. He’s also very thankful for an understanding landlord who let him skip rent for the month of September.

It all helps, but he’s still having a hard time keeping the doors open. “Whenever I used to meet with my CPA, he would say, ‘Hey, this is not sustainable, you need to change things up.’ And now, he doesn’t need to say that anymore. Now, it’s like I’m barely getting by. And he always says, ‘Are you living off of this?’ But I’m OK—at least I’m single with no kids. If I need to eat beans, I’ll eat beans.”

A talented photographer in his own right, Flynn also makes vintage tintype portraits. The photos are cast on metal plates that give subjects an otherworldly, often sepia glow. He recently moved his tintype studio outdoors to make room for social distancing. He’s offering family portraits ranging from $350 to $650, and he’s hoping people will be inspired to shop local this holiday season.

“Because it’s so little volume, now it really matters,” he says. “I’ve sold a few cameras off the shelf and it’s like, ‘Oh my god, I have a little bit of money.’ I don’t have breathing room, but at least I have enough to pay the rent and pay PG& E and keep the doors open and stay here for at least another month. Obviously, I can’t tread water forever.”\

Street Social

A dream becomes real, the world takes a turn — and fried chicken comes to the rescue.

After nearly a decade, 2020 was going to be the year it all came true. While working their way through restaurants across California, Jevon Martin and Marjorie Pier bonded one night over a 14-year-old Balvenie scotch after a shift in a Santa Monica restaurant, realizing they both often replayed the same movie in their minds, picturing what it might be like to one day open their own restaurant.

In January, when the couple, now parents to two young daughters, opened Street Social opened in a remote 300-squarefoot space in Petaluma’s Lan Mart building, word spread quickly thanks to rave reviews of dishes such as duck fat caramel corn, kohlrabi and scallop chowder, and beet tartare. On any given night, all six tables were filled, and reservations grew weekly. But when the pandemic hit, “You can’t print what was going through my mind at the time,” Martin says. Sales dropped off completely and they had to cut loose all three staff members and go it alone, reducing hours to Thursday, Friday, and Saturday nights.

“Everything went into panic mode,” Pier says. “Or pandemic mode,” Martin adds.

At first, Martin and Pier tried selling banh mi sandwiches, but even at $14, they weren’t earning enough to turn a profit. They experimented with theme nights and comfort food staples like barbecue and shrimp and grits. Nothing clicked until Martin rolled out a gluten-free fried chicken recipe that was 10 years in the making. “I never thought in a million years, I’d be doing fried chicken,” says Martin, who learned his trade at Le Cordon Bleu and more recently cooked at Glen Ellen Star. “It was just something I liked to do for fun.”

“We went with it in week two and that’s pretty much been our saving grace,” Pier says. “It’s what’s kept us afloat.” They even took the bird on the road for a few fried-chicken pop-ups around the county, calling it “The Coop.”

Sales were down at least 80% in March and April but have since hovered around 40% of normal. They’ve had success with a prix fixe chef’s table on Saturdays that allows Martin to flex his culinary imagination, one night dreaming up savory French toast with sea urchins and blueberry jam. “We’re constantly re-inventing ourselves,” Martin says. “Not to be cliché, but it seems like every other week we have to re-strategize.” One big help has been Pier’s parents, who live in Sonoma and watch the couple’s daughters every night they’re running the restaurant.

After four months of waiting for their EIDL bridge loan to be approved, Pier and Martin were told the funds had run out. Even though they qualified for partial unemployment as business owners, they had to take out a small SBA loan they will have to pay back at 3.75% interest.

On a recent Friday night, with six tables carefully spaced along a wall in the breezeway outside their restaurant, and a menu featuring melt-in-your-mouth lengua pastrami, made from beef tongue Martin bought at a small Mexican market near his home, the couple yielded an average turnout. They always shoot for around 12-16 covers a night while working as a duo, and they did half that. One party canceled after their reservation time.

They’re hoping a steady run of holiday season reservations will push them into the new year with some much-needed cash flow. After nearly a year of scraping by and juggling daily roles as server, dishwasher, chef, sommelier, and manager — have they thought about calling it quits?

“Oh no, no,” says Martin, without missing a beat. “Absolutely not. The way we got this opportunity, it’s like something you read in a book. I really believe we weren’t given this opportunity to fail. No matter what comes our way, we gotta keep pushing forward. If we fail, it’s because of us, not because of the circumstances. I believe we’re going to be here for a long time.”

Frick Winery

One man, seven acres of vines, and a mailing list that’s keeping things afloat.

“That’s one of my favorite books,” Bill Frick says with a grin, as he stands in the driveway of his Dry Creek winery, talking about Hemingway’s “The Old Man and the Sea.” It’s hardly a surprise Frick connects with the classic tale of one man’s struggle against nature. Since his wife died nearly 20 years ago, the winemaker has billed his business as “7.77 Acres and a Man.”

At 73, he does everything but pick the grapes. He sorts them, presses them, and makes wine out of them — around 1,100 cases a year – before pouring and selling them in the tasting room all by himself. He’s also a one-man shipping crew.

“A few years back, I looked into hiring a part-time employee in the tasting room so I could maybe take off a few days a year,” Frick says. “But it would cost me a minimum of $3,000 a year just for worker’s compensation. The only way I can make a living here is by keeping my overhead low. I need to pocket as much of the cash flow as I can.”

Heavy smoke from yet another wildfire hangs in the air. The owner of a nearby Dry Creek winery had just announced he won’t pick any of his grapes this year due to lingering smoke taint.

“I’m just kind of going day to day on whether I’m going to pick or not,” Frick says through his mask. He remembers making a wine back in 2008 that had faint smoky notes due to a wildfire in the region and “it almost developed a cult following. People came back for it. They loved the smoky characteristic of the wine.” He even thought about bottling a “Wildfire Red” that year.

When the pandemic hit, Frick Winery was blindsided like nearly everyone else in the industry. He had to shut down his tasting room, which accounts for about 80 to 90% of sales. “On paper it was pretty horrible,” he says, especially when considering he has no distribution in stores, only a handful of restaurants uncork his wines, and he never created a subscription-based wine club.

But Frick quickly turned to his mailing list of about 1,800 customers, alerting them to discounts and free shipping offers. “The only thing that saved me are my loyal followers,” he says. “A lot of them are really interested in my well-being.” Locals bought cases and picked them up curbside. To serve customers around the country, Frick converted his tasting room to a mailroom and began shipping and receiving seven days a week.

Sales were down around roughly 40 to 50% the first two months, but then “June was really bad.” As tasting rooms were allowed to reopen, he moved tastings outside to the parking lot, where he could hold forth over a large table and customers could space out by appointment only.

In a one-on-one setting, it’s his story that sells the wine. Nearly every person on his mailing list has visited the winery at some point and discovered his niche of Rhône varietals amid a sea of Zinfandel, Cabernet, and Chardonnay, often learning how to pronounce “counoise” and “cinsaut” along the way.

It’s an unlikely scenario for a guy who was a bit of a loner as a kid: “I don’t know too many people. I don’t enjoy talking.” His late wife, Judith Gannon, an artist who often ran the tasting room, would be pleasantly surprised at his outgoing nature these days, he says with a laugh. And she’d probably be impressed with his online pivot during Covid-19 as well.

“I can survive this pandemic,” he says. “But I’m no spring chicken, and I’m getting sick and tired of these fires. In my fantasy, I start imagining, ‘where can I go and live at peace and not have to worry?’ But everywhere I look has the same fuel in place for these kinds of fires.”

In the Making

Two artists bet on an antidote to mass consumerism with locally made gifts.

As artists who opened a retail space, Jennifer Conner and Siri Hansdotter like to joke that they’re not “numbers people.” But the two friends have had to become bean counters over the past eight months, even if the numbers aren’t what they dreamed of eight years ago when they first imagined their downtown Petaluma gift shop and studio, In the Making.

In the first months of the pandemic, sales of their handcrafted jewelry, handbags, clothing, art, and household items — all made in Sonoma County — dropped to almost nothing. “It was terrible,” says Conner, who, in addition to running the store, is a designer who crafts vegetable-tanned leather into handbags that will last a lifetime. “I don’t we think we sold anything. People were terrified to spend any money.”

“People were only buying toilet paper,” says Hansdotter, who creates one-of-a-kind jewelry out of sterling silver, yellow and rose gold, and precious stones.

It wasn’t until customers qualified for unemployment that the card swipers lit up again. “As soon as people started getting checks, the online sales picked up and I had a good little run,” Conner says.

Then in July, when the $600 weekly federal stimulus ran out, sales plummeted again. The two split their $2,000 rent with a furniture maker in the back of the shop, but even, then they couldn’t pay it every month as they had since opening in 2017. “We paid what we could,” Hansdotter says. “You can’t bleed a stone, and we felt like what we paid was fair given the circumstances.”

Early on, Conner and Hansdotter applied for PPP loans and were rejected, so both went on unemployment. If sales were down 80 to 90% in the spring, by the summer sales had picked up to about half of what they were the previous summer, and they were back to paying full rent. Online sales grew, and people were allowed to once again enter the store in limited numbers.

“We have customers who come in and they don’t need anything, but they come in to support us,” Conner says. “Those are the people who are keeping us afloat. One woman came in and bought an expensive bag and said, ‘I just want to support you.’ Things like that kind of make you tear up a little bit.”

As holiday shopping ramps up, they’re hoping for a big push into 2021. Conner stocked up on American-made leather back in September when suppliers were at least two months delayed on orders. Hansdotter is keeping her jewelry cases well stocked, and even with an uncertain future, she has hope for the value of locally made goods.

“It’s not mass consumerism. It’s important for people to feel like they can buy something that’s not disposable,” she says. “They’re going to have these things for the rest of their lives. Their kids are going to have these things. It’s an heirloom you’re going to pass down. I think today more than ever, that message is really important.”

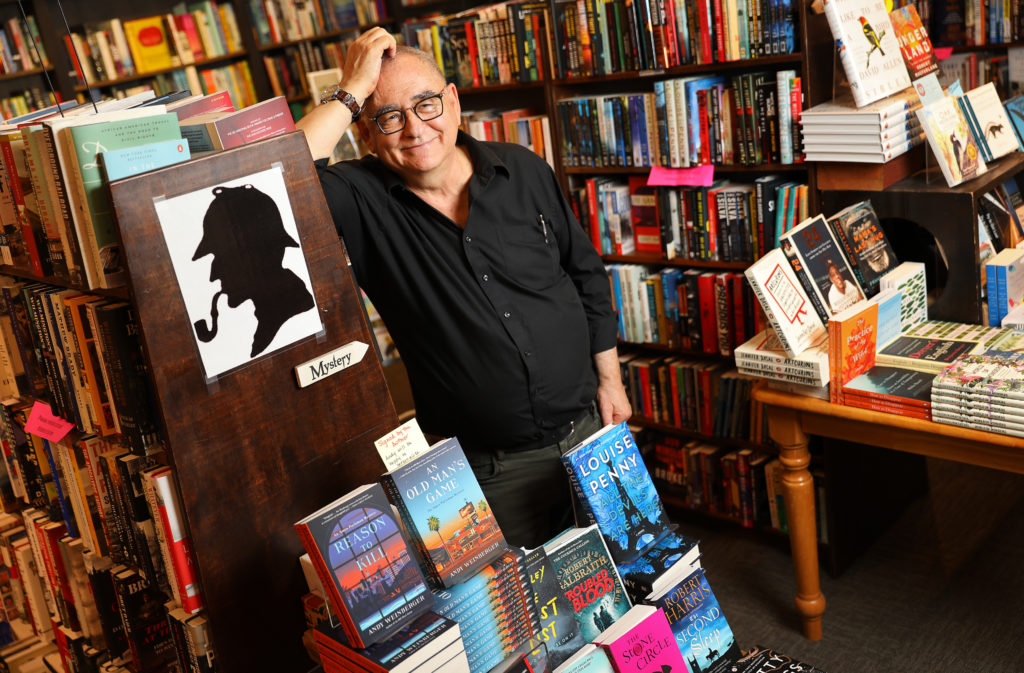

Readers’ Books

An independent bookseller fights to continue the legacy of his late wife.

It doesn’t take long for Readers’ Books owner Andy Weinberger to get to the punch line: “In the book business they spell retirement ‘D-E-A-D.’” You work until the very last breath, he explains. “Golden parachute to what? They can carry me out on a board, that’s fine.”

Even though he’s in it for the long haul, Weinberger admits it started feeling like final days when sales dropped 61% in April and 52% in May. But booksellers have always found a way to persevere — beyond steep Amazon book discounts, beyond forecasts of waning readership, and beyond the latest plague.

In the early days of the pandemic, “we were in a bit of shock,” he says, but it didn’t take long to pivot and start offering no-touch book pickups left on the back patio in the Readers’ Garden. The shop “managed to eke out some sales” as one employee made book deliveries by bicycle and others mailed online orders.

“My landlord said to forget about the rent, so I conveniently forgot about it,” he says, at least for a month. And other support came out of the blue. “I had one woman who sent a letter in the mail with a check for $1,000 and a note that said, ‘We want to see you around.’” Weinberger applied for a PPP loan in March and eventually got $27,000 in support, which meant that many of his employees could go off unemployment. “In theory, you have to pay it back,” he says. “But they have loan forgiveness if you use it to pay your payroll and your mortgage or rent, so that’s what I did.”

After 29 years, “fortunately or unfortunately, we’re the only bookstore in town,” he says. That means while people were stuck at home with ample time to read, the 2,000-square-foot shop, stocked with more than 18,000 titles, was the only local option. Readers’ Books hosts a regular slate of author events, and has brought in such figures as Bill Moyers, Deepak Chopra, and Anthony Bourdain over the years. But all live events have been canceled since March, though Weinberger did manage a virtual event in September to read from his own book, “Reason to Kill,” the latest in a series of mysteries.

Though sales have started to bounce back, he’s hoping things will pick up further during the holidays, and that people will turn to the annual CALIBA (California Independent Booksellers Alliance) end-of-year booklist for shopping tips. And he plans to mount his annual Book Stars program, where customers donate money for books for kids in Sonoma Valley who don’t have enough to read. “This year more than ever, there’s a need for this,” he says.

Undaunted by the pandemic, what keeps him going is not only the routine of work — putting in several hours in the store in the morning and then writing mystery novels in the afternoon — but also the spirit of his wife Lilla, who died suddenly last year. “It was a big shock to my system, and this store is like family to me,” he says. “It’s a legacy I want to continue for her.”