This article was originally published in 2016, 40 years after the installation of “Running Fence.” Christo, who made monumental art around the world, died at 84 on May 31, 2020. Jeanne-Claude, his artistic and life partner, died at 74 on Nov. 18, 2009.

The hamlet of Valley Ford hasn’t changed much in the last four decades. There’s more traffic, of course: It’s located on scenic Highway 1, and Bodega Bay is just 8 miles to the west. But Dinucci’s Italian Dinners is still there, serving the family-style meals that made its initial reputation more than a century ago.

Local ranchers still come to the Valley Ford Market for coffee and the latest talk on lamb prices and government regulation. And the land itself seems immutable: The rolling pastures broken by eucalyptus windbreaks — speckled with fat sheep and sleek cattle — present a prospect as timeless as the nearby Pacific Ocean.

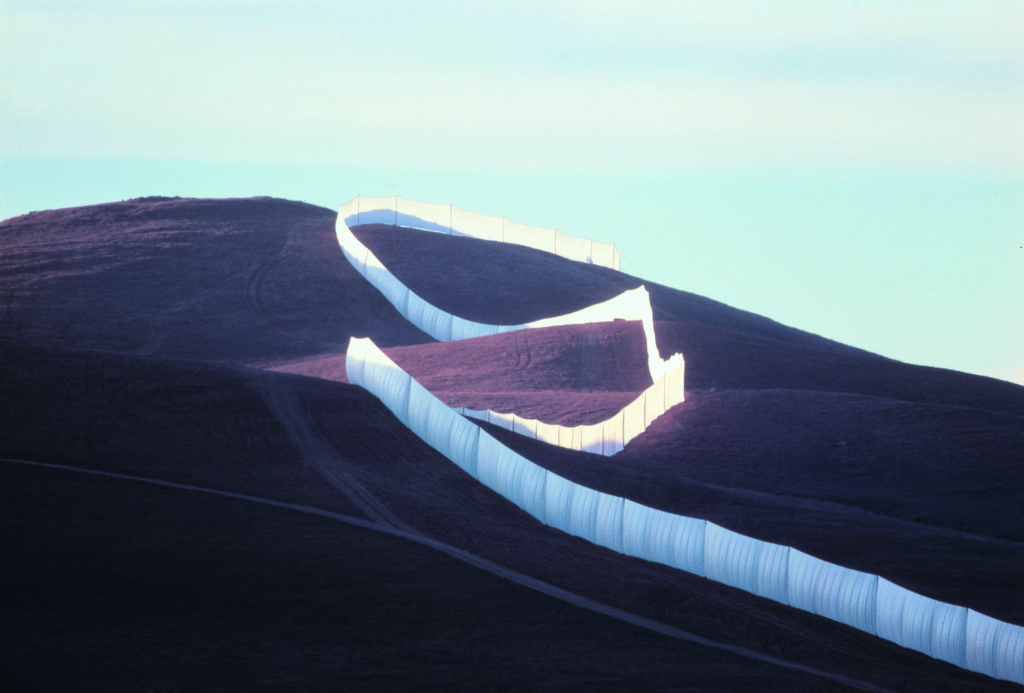

But something happened here 40 years ago that changed everything. A discreet monument marking that event stands at the Valley Ford post office, a single, corroded metal pole 18 feet high, with a small commemorative plaque at its base. It was at this spot that “Running Fence” came through, completed on Sept. 10, 1976.

If you saw the fence then, you can stand next to the pole now, close your eyes and see it again, with almost shocking clarity. You can understand now that it meant much more than you thought it did at the time of its installation.

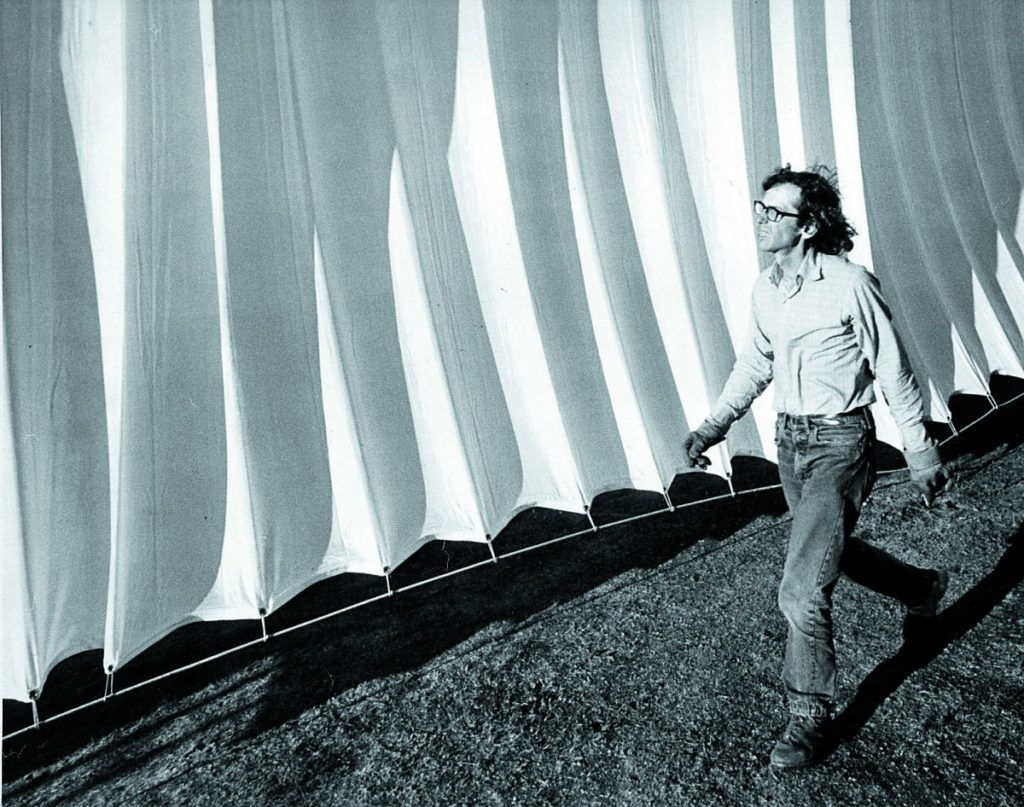

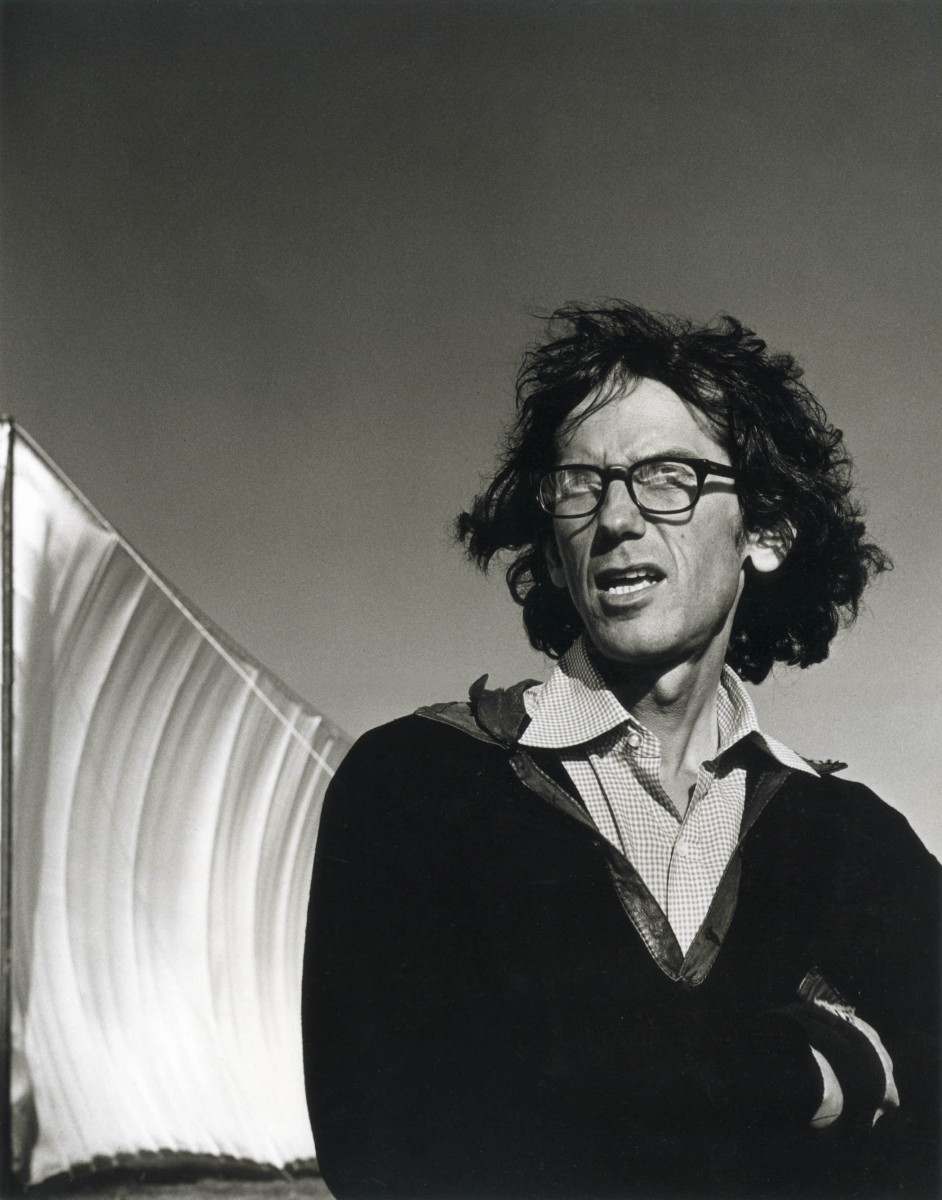

Joe Pozzi remembers when a slight-framed man with long hair, massive horn-rimmed glasses and craggy features came to his family’s ranch near Estero de San Antonio. It was in 1972, and Pozzi and his siblings were engaged in the quotidian duty required of anyone involved in a dairy operation: milking the cows.

“We were in the barn and we saw Dad outside talking to this guy,” recalled Pozzi, then a pre-teen. “And when Dad came into the barn, we asked him what was going on, and he said, ‘Oh, some damn hippie wants to build a fence for us. I told him to come back later.’”

That “hippie” was Christo — Christo Vladimirov Javacheff — now hailed as the world’s foremost installation artist and one of the great creative visionaries of the past five decades. While it’s true that he came to the Pozzi ranch to build a fence, it wasn’t as an itinerant laborer hoping to make a few bucks stringing barbed wire.

“Christo was Bulgarian and his English wasn’t that great then, so Dad misunderstood him,” Pozzi said. “But Christo came back with his partner, Jeanne-Claude, and my mom brought out the bread, cheese and salami, like the west county Italian farmers always did when they had visitors. And Christo had this book with him, about something called the hanging curtain at Rifle Gap.”

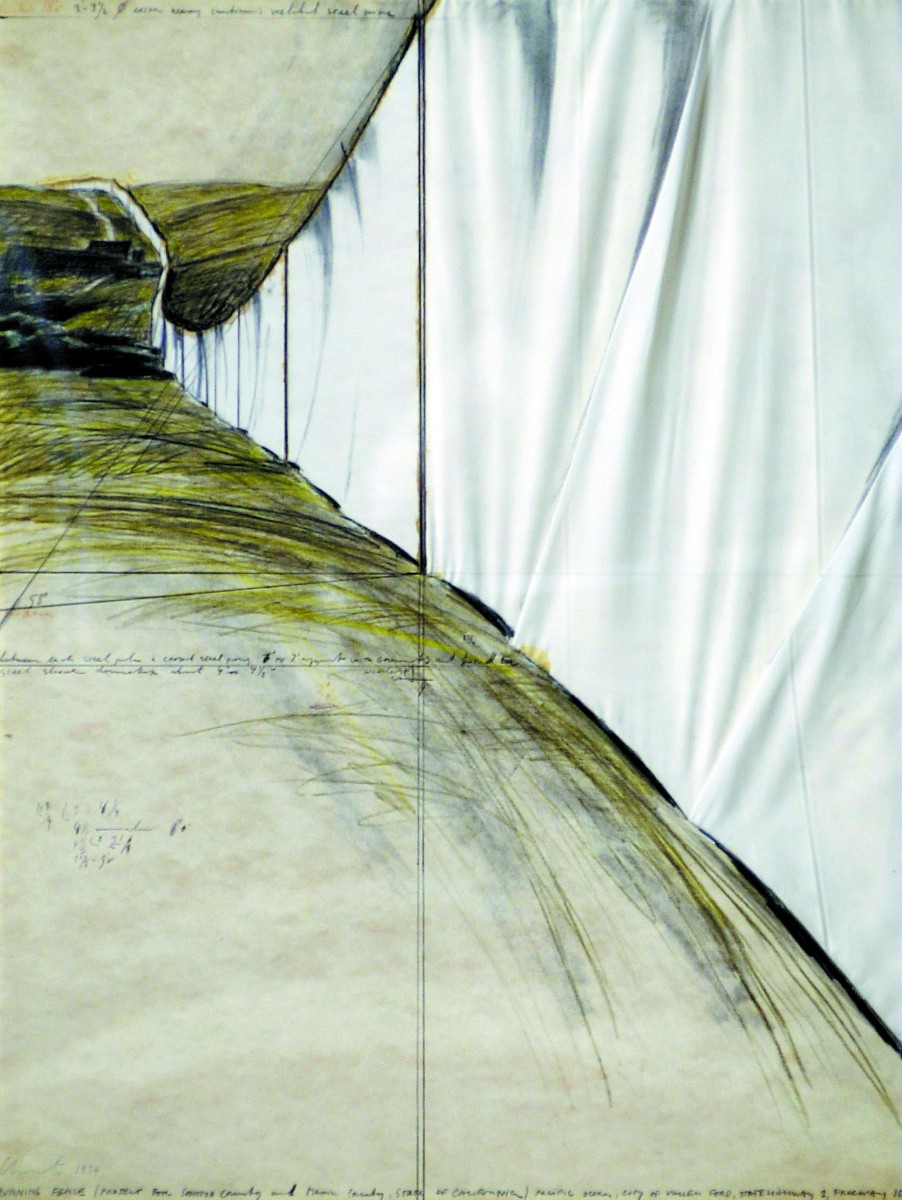

That was Rifle Gap, Colo., and “Valley Curtain” was a project that Christo and Jeanne-Claude had recently completed, a 200,200-square-foot swath of fabric draped across a steep mountain pass. As everyone ate the antipasti, the Pozzis politely listened to Christo’s proposal. He planned another project, this one for Sonoma and Marin counties, a fence of fabric running sinuously across the land from Highway 101 to the sea. It would be about 25 miles long and almost 20 feet high.

By the end of the visit, Pozzi said, his parents still weren’t completely clear on the concept, but they were sure of one thing: They liked Christo.

“He was incredibly charismatic,” Pozzi said, “but it was more than that. He was genuine. There was a warm human quality to him that you just felt. There was nothing slick or pretentious about him. Ranchers and farmers intuitively sense character in a person. He didn’t get the ‘Running Fence’ built because he sold anybody around here on the idea. They got behind him because they liked and trusted him.”

Christo returned to the Pozzi ranch several times over the next few months, and ultimately formed a deep bond with the family. At the same time, he visited other dairy farmers and ranchers who owned land along his proposed route for the fence. He ate at their tables and drank their wine.

Christo was in no hurry, Pozzi said, as he and Jeanne-Claude seemed to relish the human contact. It was evident they enjoyed immersing themselves in the west county’s agrarian culture.

“Everyone came to understand Christo was an artist, an important artist, and that the ‘Running Fence’ was a major art project,” Pozzi said. “But that wasn’t why he appealed to us. It was more that he shared similar qualities with the agricultural community. It’s something of a paradox. We’re independent, but we also rely on each other, we’re ready to help out at a moment’s notice. And we like to get things done, to conceive a project and then work hard to see it through. Christo had a project that he wanted to get done. He wasn’t going to step on anyone to do it, but it was important to him, and he asked for our help.”

Christo and Jeanne-Claude ultimately enlisted 59 families whose properties fell within the proposed route of the fence. The ranchers and farmers weren’t merely acquiescent, however; they had become committed partisans for the project.

At the same time, news of the fence generated fierce push-back, primarily from environmentalists concerned about impacts on the land, and also from locals who were offended by promotion of the project as “art.” They formed the Committee to Stop the Running Fence, and vowed to send Christo fleeing from Sonoma.

The upshot of the discord was a seemingly endless series of meetings convened by the California Coastal Commission, the Marin County Planning Commission and the Sonoma County Planning Commission. The process was rancorous and dragged on for more than three years.

“I remember at one point somebody declaring that the fence was ‘fascist art,’” said Brian Kahn, then a freshman Sonoma County supervisor who had been newly appointed to fill a vacancy. “I didn’t physically roll my eyes, but I rolled them internally. I was perplexed by the furor. The fence drew all these incredibly intense emotions that — from my perspective, at least — it didn’t warrant. Politics and art don’t mix well, and my bias has always been to let artists do what they want.

“But the fence came along just at a point when land-use policy was the primary matter of concern in the county, and it seemed to galvanize emotions on all sides of the issue. In a way I didn’t realize at the time, it focused people on the landscape and the impact our land-use policies would have on the future of the county.”

But if opponents inveighed furiously against the project at the meetings, supporters — mainly ranchers and dairy farmers — spoke passionately in its favor. Christo seemed utterly serene. He spoke in defense of his art, and his disposition was always sunny; he never seemed worried, or even slightly anxious.

“He said on more than one occasion that the process, all the meetings, the environmental impact studies, were part of his art,” said Barbara Gonnella, owner of the Union Hotel in Occidental and Joe Pozzi’s sister. “And that was the absolute truth. If he hadn’t been able to build the fence in the end, I’m sure he would still have considered the project a success.”

Earlier this year, Gonnella hosted a screening of a film about “Running Fence” that was funded by the Smithsonian Museum of Modern Art. For Gonnella, the documentary had special resonance because it featured one of the last interviews with Jeanne-Claude before her death from a brain aneurysm in 2009.

“By the 1990s, their work was a complete collaboration,” Gonnella said. “It was never just ‘Christo.’ It was always ‘Christo and Jeanne-Claude,’ and to me, that emphasized their connection with each other and humanity at large. Christo’s art is about more than just objects and materials, more about themes, even. It incorporates the landscape and the people on it, and the relationships he builds with those people.

“Our family is still in close contact with him. When our mother died, he was the first person to send flowers. When he’s in the area, he eats at the Union Hotel. My daughter just came back from visiting his latest installation (“The Floating Piers” on Lake Iseo, Italy). He’s still part of our lives. His work still affects us. He still affects us.”

Ultimately, of course, the fence went up. Scores of volunteers laid out the route, sank the posts, strung the cables, hung the fabric. Christo was right there among them, wearing an OSHA-required hard hat, blissfully shouldering his share of the grunt labor.

“I was 13 at the time,” Pozzi said, pointing out the path the fence took across the gentle hills south of Valley Ford, now empty save for grass undulating in the wind and myriad grazing sheep. “I think I was the youngest volunteer on the installation. It was an incredible experience, and then, two weeks after it went up (in 1976), we took it down. Two months later, you couldn’t tell it had been there. But my memory of it is still so vivid. It changed people’s lives, and for the better.”

Dave Steiner, a Sonoma Mountain grape-grower who was appointed to the Sonoma County Planning Commission shortly after the fence went up, said people shouldn’t confuse Christo’s melding of government processes into his art with reflexive acquiescence to official dictates.

“Great artists don’t yield to cultural or political pressures,” Steiner said. “They are naturally subversive, and Christo certainly was in that mold. When the Coastal Commission didn’t grant him a final permit to run his fence into the sea, he did it anyway. He used government to make a point in his work, but in the end, he was happy to defy government. That defiance was part of his work, too. And I think anybody who was around here at that time and had his or her head screwed on straight said, ‘Right on!’ when that happened. The fence was always supposed to run into the sea. The entire project would have been diminished if it had stopped at the shore.”

After serving as a Sonoma County supervisor and the president of the California Fish and Game Commission, Brian Kahn moved to Montana. For a time, he directed the Montana Nature Conservancy. He now devotes himself to journalism, authoring books on environmental policy and field sports, and hosting “Home Ground,” a public-issues radio show broadcast across the intermountain West.

But he still gets back to Sonoma County with some regularity, and for the most part, he’s happy with what he sees.

“Through the mid-’70s, the county was focused on — actually divided by — a proposed general plan,” he said. “It was going to determine whether growth would be contained and orderly, or largely unregulated. The plan finally was adopted in 1978, and I’m convinced the fence was a major factor. It made people think about the land and their relationship to it. And when I drive around the county now, I see that the plan has pretty much held together.

“Santa Rosa and Rohnert Park may have merged more than was intended, but Sonoma Valley, the west county — those landscapes are largely intact, despite all the population pressures. It’s a wonderful thing to see. It’s a tremendous collective accomplishment.”

Indeed, the shift toward popular support of a general plan seemed to coincide with the completion of “Running Fence.” The project not only brought Sonoma County to the attention of the world, it also, somehow, brought the people of Sonoma County together.

“It was strange,” said Gonnella as she sat in the shadowed dining room of the Union Hotel following the lunchtime rush. “Once the fence started going up, once people could drive out and see this miraculous thing unfolding across the land, all the bitterness, all the protests, just kind of — stopped.”

She paused, looking out a window. Her eyes were moist, and when she spoke again, her voice was charged with emotion.

“I was only 17 then,” she said. “I loved living out in the west county. Everybody knew each other, most of the families were from the same region in northern Italy. But when the fence came, I got a sense of something bigger. The way it looked running across the hills, shimmering, changing colors in the light and the wind. I was so young, and it was so — so romantic. So incredibly romantic. I felt like my heart was going to burst.”

Selected Christo Installations

1962 – “Oil Barrels”- Germany

Jeanne-Claude and Christo created a piece in response to the building of the Berlin Wall, blocking off the Rue Visconti in Paris with a wall of oil drums. They convinced police to allow the installation to remain for a few hours.

1972 – “Valley Curtain” – Colorado

An orange curtain made from 200,200 square feet of woven nylon fabric was stretched across Rifle Gap in the Rocky Mountains. An earlier attempt was shredded by wind and rock.

1976 – “Running Fence” – California

1983 – “Surrounded Islands” – Florida

Eleven islands on Biscayne Bay were surrounded with 6.5 million square feet of floating pink woven polypropylene fabric covering the surface of the water and extending out from each island into the bay.

1991 – “The Umbrellas” – the U.S. and Japan

A temporary work realized in two countries at the same time, it was comprised of 3,100 opened umbrellas in Ibaraki (12 miles of them) and on Tejon Pass, along Highway 5, in Southern California (18 miles).

2005 – “The Gates” – New York

More than 7,500 gates made of saffron-colored fabric panels were installed in New York City’s Central Park, a golden river appearing and disappearing through bare tree branches.

2016 – “The Floating Piers” – Italy

From June 18 to July 3, Lake Iseo in Lombardy was partially covered in 62 miles of shimmering yellow fabric, supported by a modular dock system of 220,000 high-density polyethylene cubes floating on the surface of the water.