Native American basket weavers follow differing traditions and use various techniques. But they do seem to agree on one thing: That their least favorite question people ask them about basketry is, “How long does it take to make a basket?”

Even though the question itself is not meant to be offensive, it betrays a basic misunderstanding of basketry. It’s part of daily family and tribal life, and carries a strong spiritual connection between Native Americans and nature. Basket weaving is a lifelong endeavor, often starting in childhood, that takes a long time to master.

“We say it takes a lifetime,” said Clint McKay of Forestville, president of the California Indian Basketweavers Association.

Outsiders may see baskets as souvenirs produced quickly in large quantities for sale at roadside stands, but to the weavers, baskets are useful tools, family treasures and an expression of tribal love for the land and all it provides.

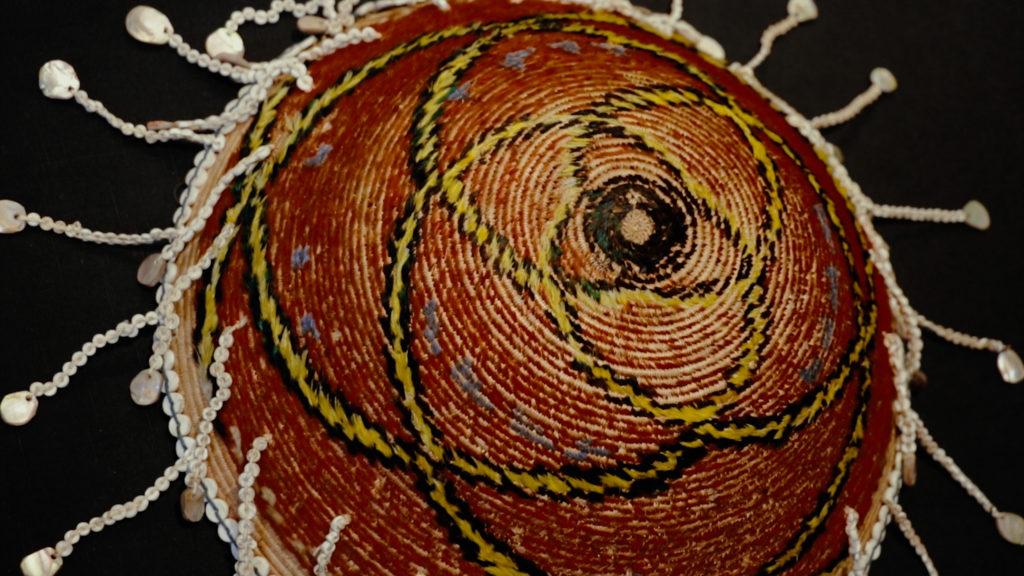

Watch this video to learn why the basket-weaving tradition is an essential part of Pomo culture.

Weaving is not simply a craft, said McKay, an enrolled member of the Dry Creek Pomo, Wappo and Wintu tribes. To many, weaving is a way of life.

“To me, weaving is much more than an art form,” he said. “It’s the very essence of who we are as an Indian people. There has not been one aspect of our tradition that has not been touched by basketry.”

Baskets traditionally have been used to collect, clean, store and prepare food, as well as for catching fish, trapping birds and a variety of other needs.

“We carry our babies in baskets,” McKay said.

Susan Billy of Ukiah, who apprenticed as a young adult with famed Pomo basket weaver Elsie Allen starting in the early 1970s, already had been surrounded by the basketry tradition since her childhood.

“For thousands of years, we have been making baskets for every purpose, from birth to death. We made baskets because we had to. We developed basketry to such a high level that we didn’t need to develop pottery,” she said.

Even though baskets filled a practical need, there is still much more to the tradition than that, Billy explained.

“For me, basketry always has been a spiritual process,” she said. “I don’t consider it a craft. We have to pray, and ask the plants if they want to be in a basket.”

Authentic basket weaving depends as much on gathering the right natural materials as on technique.

“If you don’t gather, you don’t make baskets,” Billy said.

Materials used to make baskets include willow, redbud, bulrush and sedge grass, and although they’re found in nature locally, it wouldn’t be precisely correct to say the specimens used to create hand-made baskets are growing wild.

“We tend these sourcing sites with tenderness and respect,” Billy said. “They’re more like tended gardens.”

Some weaving skills can be taught in classes but, traditionally, weavers have learned the entire weaving culture from their families.

“My mother was a weaver, and her mother before her,” said weaver Nancy Napolitan of Windsor, whose sister also is a basket weaver.

“It was part of what I grew up with. My family knew basketry.”

Although Napolitan shares other weavers’ dread of the question, “How long does it take to make a basket?” she offered an answer.

“If you sat there with a machine, you could put one out in an hour,” she said, “or you could spend several years. It’s a complex thing.”

The Santa Rosa Junior College Multicultural Museum houses, displays and preserves the Elsie Allen Pomo Basket Collection. The museum is open 9 a.m. – 2 p.m. Monday-Thursday. The collection can also be viewed online: museum.santarosa.edu/exhibit/6. Learn about Elsie Allen in this Press Democrat article.