Near the end of his career, artist Richard Diebenkorn realized he needed to escape the very place he was famous for painting — Ocean Park, the bustling Santa Monica neighborhood that inspired his widely celebrated series of mesmerizing, abstract patterns and delicately hued landscapes.

After two decades in west Los Angeles, he had begun to feel “hemmed in and closed in,” he told friends. Never one to crave the limelight, he cherished his alone time in the studio, something that was harder to come by each day.

So, in the mid-1980s, he and his wife Phyllis began to search for a change of scenery, embarking on long road trips throughout California, the Southwest and the Midwest. They looked at a ranch in Montana. They thought about returning to Albuquerque. Then they pondered relocating to Springville, San Luis Obispo, Sonora and Reno before landing back in the Bay Area, where he had attended Stanford University in the 1940s and painted a well-known series of Berkeley paintings in the 1950s.

On the advice of friend Dick McDonough, they toured northern Sonoma County. One day, standing in front of an 1878 white farmhouse in Alexander Valley, Richard Diebenkorn fell for a new sense of place. It was not just the house, topped off with an ornate widow’s walk and meticulously restored by its previous owner, a former racing jockey. Nor the remote location on 6 acres, set back from winding West Soda Rock Lane and framed by a white corral fence. But also the surrounding vines, nearby Russian River and a towering, siren-like peak in the distance. Miles from the ocean, it was a landscape less defined by the Pacific blues of Ocean Park, expanding the palette to vibrant greens and reds — even yellow and gold when the spring mustard was in bloom.

Gazing across quilted vineyards, Diebenkorn could see Mount St. Helena from almost anywhere on the property. It inspired him. Later, he would introduce it to newcomers as “my Montagne Sainte-Victoire” or “Montagne de Cézanne,” in honor of the post-impressionist French painter, who recreated the iconic French mountain dozens of times.

“What drew him to (the house) was its simplicity and its lack of ostentatiousness,” says Andrea Liguori, executive director of the Richard Diebenkorn Foundation in Berkeley. “They chose that house visually, and he pursued it through his real estate agent and learned that it was, in fact, available. So, he manifested their moving into that house, like people generally can’t do now, where you just fall in love with a house.”

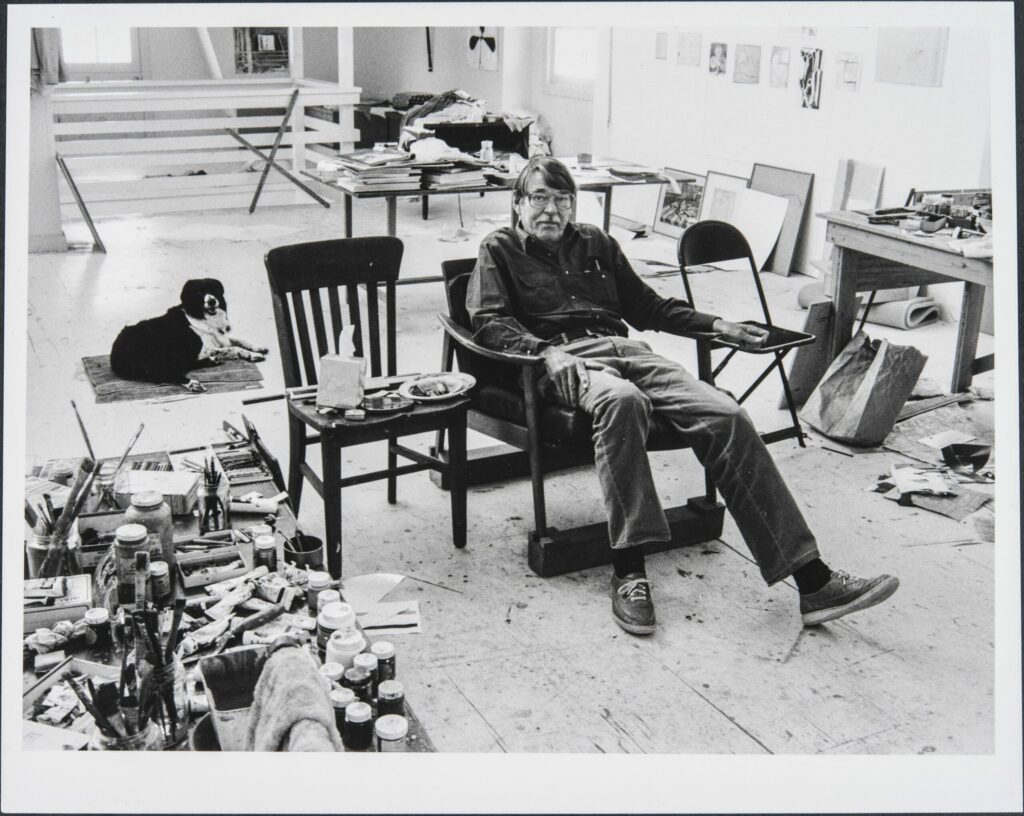

In 1987, after buying the two-story, five-bedroom white farmhouse (for $555,000 at the time), the Diebenkorns hired Berkeley designer Jay Claiborne to convert the barn-style garage into an art studio, adding a stark, angular second floor with clerestory windows that allowed natural light to fill the space. Although Claiborne installed a fancy new lighting system, Diebenkorn was content to use the simple, hooded clip-on aluminum lights he’d hung in studios for decades.

Tension Beneath Calm

By the spring of 1988, the great American painter had traded fast-paced Los Angeles for the slow hum of rural Sonoma County. Often referred to as “the Healdsburg years,” it’s a chapter in his life and a period in his work that doesn’t always get a lot of attention.

In an interview a few months before moving, Diebenkorn seemed almost anxious. Surrounded by paintings in his Ocean Park studio, Diebenkorn admitted “my fingers are crossed” about the move. He had fallen for Alexander Valley, but he added, “my concern is that it’s possibly just a little bit too beautiful. There won’t be enough irritants. There’s plenty of that here (in Los Angeles). I suppose I can always come back here and be irritated.”

It had always been a part of his process, that “tension beneath calm” referenced throughout his career. A calm, bespectacled, unpretentious man, Diebenkorn also had a wry sense of humor, remembers printmaker Renée Bott, who worked with him in the ’80s and ’90s on several large-scale prints he made at Crown Point Press in San Francisco. Diebenkorn and his close friend Wayne Thiebaud were two of the first artists to experiment with etchings and intaglio at the pioneering press.

The necessary “irritants” he mentioned were very much a part of his process, she says. “His paintings were about beauty and composition, and the beauty that happens when something’s well composed,” says Bott. “But he also wanted to create tension in his work, and I think he lived that way, too.”

She once worked on prints with him in a makeshift San Francisco studio, salvaged from a former autobody shop after the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake, as rats scurried throughout the space. “It was really beautiful to watch him work, because I always felt like he was solving a problem,” she says.

In his Alexander Valley studio, Diebenkorn often settled into a favorite chair he’d brought from Ocean Park, staring at works-in-progress for hours. “He had this energy for the struggle in the studio,” says foundation director Andrea Liguori. “For him, the act of making a painting was the goal. It was the process of figuring out that was of more interest to him, ultimately, than the end product.”

Looking at his writings over the years, she says, “It’s really fascinating that when he got too comfortable, he complained about it, because then there was no struggle anymore.”

Bott visited the Diebenkorns several times, often dining outdoors eating lunches that Phyllis prepared, beside a long, black-tiled pool and a rolling grass lawn. “It felt like a scene out of some romantic movie,” she remembers. “I felt like I was in Provence.” But what she remembers most about Diebenkorn is his humble nature — “very introspective and quiet.”

When he moved into his new Healdsburg studio, he brought two unfinished “Ocean Park” canvases from Santa Monica. At around 8 feet tall, they were so large that his contractor had to raise a gateway arch near the entrance to the property, so the moving truck transporting the paintings could pass underneath.

A Refuge in the Valley

It didn’t take long for the painter to feel at ease in his new backdrop. In 1988, when a “CBS Sunday Morning” production crew came to visit, Diebenkorn looked every bit the artist in transition, acclimating to his new surroundings, walking through autumnal vineyards with his dogs Amie and Lucy, talking about sketching scenes along the banks of the Russian River. He seemed eager to explore the light and geometry of the area.

“I think what an artist does is all about what’s around him,” he told the interviewer. “His environment — cultural, physical and visual.”

As the scenery changed, so did his palette — not immediately, but measured over time with daily walks through the vineyards. “After more than two decades in Santa Monica, his brain and body must have been madly recalibrating from all of the change: discernible seasons, a new spectrum of California colors (more greens and yellows, fewer blues), a jarringly different vastness (no more miles of sand and crashing waves, just parallel lines of vines extending up into quiet mountain ranges),” his granddaughter Phyllis Grant, a Berkeley author, once wrote.

In Santa Monica, Diebenkorn had often chatted over his fence with his neighbor Ry Cooder, the blues and world musician. His L.A. social circle included painter William Brice, film producer Ray Stark, art dealer Irving Blum and playwright Edward Albee. In Alexander Valley, Richard and Phyllis found new friends, making an instant connection with Dick and Mary Hafner, who owned nearby Hafner Vineyards. A former journalist, Dick Hafner had worked in public affairs at UC Berkeley, not far from where the Diebenkorns lived in the ’50s and ’60s.

“It was very much a symbiotic relationship,” says son Scott Hafner, a managing partner at the family winery today. “They respected that someone moves to this area, probably in part because they want the solitude, and that lack of glitziness has some attractiveness.”

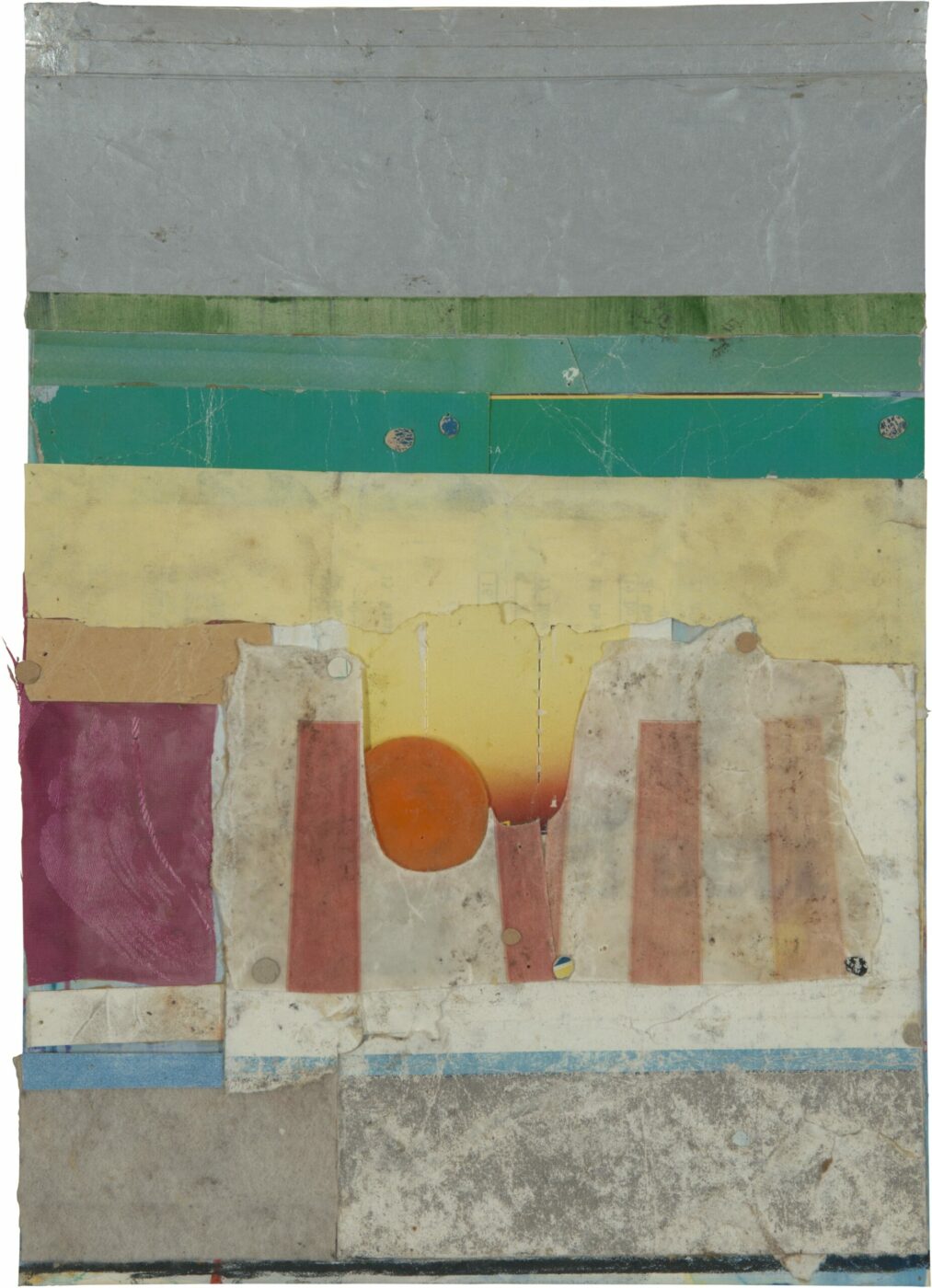

The two couples spent many late evenings around a table, drinking wine and talking — sometimes at the Diebenkorns’ farmhouse, other times on the terrace overlooking the valley from the Hafner property on Pine Flat Road. The couples often hiked through the vineyards or along the river together, too. On his sojourns, Diebenkorn would pocket scraps of litter, like bottle caps, or bits of paper or plastic. The brightly colored objects would often find their way into his art, appearing in the collage “Skating Down the River at Soda Rock,” a gift to his granddaughter before she moved to New York for college.

But at age 66, Diebenkorn’s health began to decline. A few months after the “CBS Sunday Morning” episode aired, he took a winter walk and felt out of breath. He had to lay down and rest. Doctors later discovered a damaged aortic valve, and during surgery he developed an infection.

For a while, his studio was moved to a location inside the house. After a six-month recovery, he wrote a letter to his friend, the art consultant Mary Keesling, saying, “I am working daily in my Healdsburg studio, and think I should have come up here years ago.”

In 1991, Press Democrat reporter Tim Fish sat with Diebenkorn on his front porch, overlooking the vineyards in the distance. Fish remembers he was allotted one hour for the interview, and how Phyllis “was very protective of his time and level of energy.”

“He was fragile, but still mentally sharp,” recalls Fish, now a senior editor at Wine Spectator. “He seemed to truly enjoy talking about his life and work.” Fish took the photo that appeared in the newspaper — a portrait of Diebenkorn standing, his glasses removed, both hands in his jean pockets — because Phyllis wouldn’t allow a photographer.

While they were sitting on the porch, Diebenkorn pointed again to the westward summit he so loved.

When Fish asked him if Alexander Valley, like Ocean Park, had influenced his new work, Diebenkorn said, “That’s very hard to tell. I don’t go to a place for that reason. When I saw this place, I knew it right away. If I like a place, I kind of have a rapport with it.”

What Might Have Followed

It’s difficult to predict what effect Alexander Valley might have had on future work. In 1992, Diebenkorn’s health continued to worsen, and in March of 1993, he died of pulmonary failure in Berkeley. A New York Times obituary described him as “one of the premier American painters of the postwar era.”

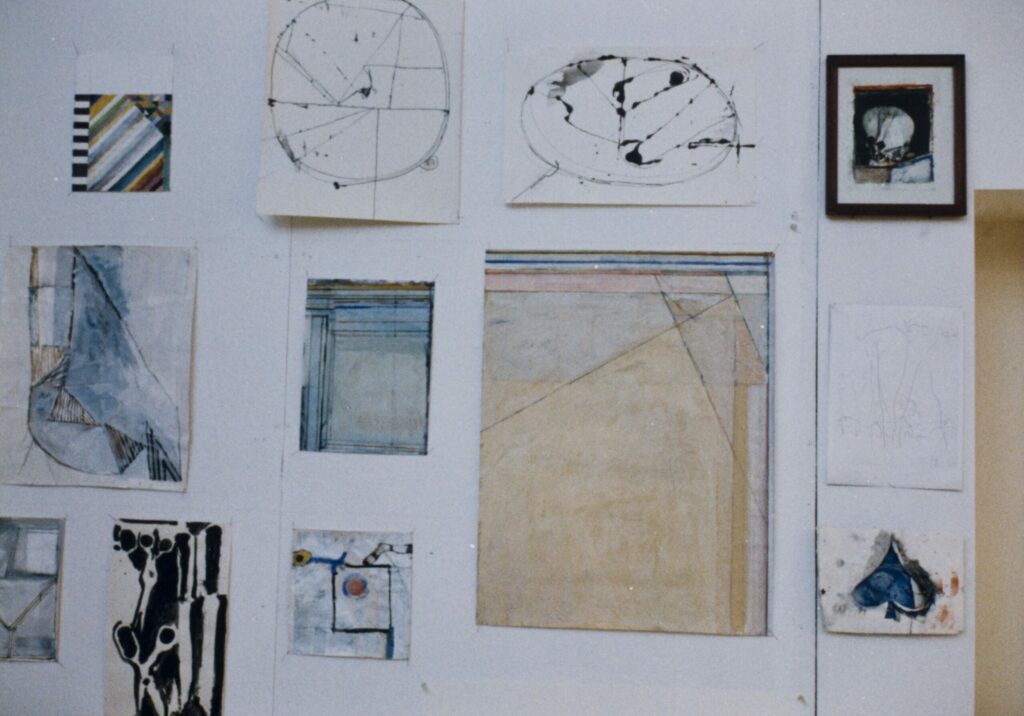

In the five years he lived in Alexander Valley, the two 8-foot-tall, unfinished “Ocean Park” series paintings he brought from Santa Monica were never unwrapped, and never hung on the hooks driven into the wall to support them. In fact, after moving to Northern California, he would never paint on canvas again. He only produced works on paper — with charcoal, gouache and watercolor — a practice he often undertook while transitioning to a major new period of creativity.

Over the years, he wrote countless notes to himself in the studio on scraps of paper that he saved as reminders or words of encouragement to stay the course. One of them reads, “Have confidence in this landscape thing — even though it seems to have gone to hell today.” Another says, “Each painting requires weeks of dismal and embarrassing manipulation of meaningless lines and spaces. I never know what funny shift will put me on the track.”

During this time, even as he retreated to the country and focused on more intimate works on paper, his international fame continued to grow. His large-scale paintings were exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, fetching more than $1 million from art collectors, and he was the subject of a feature profile in The New York Times Magazine in 1992.

“He was looking for a change of place, a change of space, a change of light, a change of look, and I think he really happily found that up there,” says John Van Doren, owner of Van Doren Waxter gallery in New York. In 2014, the gallery worked with the Diebenkorn family to stage the well-received exhibit “The Healdsburg Years 1988-1993.”

Looking back on this time of transition, Van Doren says, “It’s a shame that we don’t know where that went, because he was clearly getting into new approaches and new forms in the work that he was making. We have what we have, which is glorious.

But, of course, it would have been great to know what followed.”

One work in the 2014 exhibit that might be hard to pick out of a lineup as distinctly Diebenkorn, is a watercolor and graphite still-life of a skull, conjuring a classic memento mori symbolism dating back to the Renaissance. “I can’t help but look at that skull and think that there’s at least some reference to the passage of time,” says Van Doren.

Taking a closer look at some of his last works, Liguori and other art scholars have noticed how “the work got smaller, with rounder shapes and kind of mysterious with playful symbols… The little wheels and little circles of curiosity, little eyes and buttons and these fun shapes.”

When Diebenkorn was a child, his maternal grandmother gave him a set of playing cards that reproduced the medieval Bayeux Tapestry. He was also obsessed with the imagery of clubs and spades. Similar symbols of heraldry had cropped up in previous artwork over the decades and then reemerged during his time in Healdsburg.

“It makes you wonder, was he aware that he was dying soon?” says Liguori. “Was he thinking about childhood? Was he having this sort of summation of life experience that people can have when they’re in their last few years of life?”

Today, his daughter Gretchen Diebenkorn Grant still owns the white farmhouse on West Soda Rock Lane. She works with the Richard Diebenkorn Foundation to help preserve her father’s legacy and make his archives available to curious admirers and researchers. After the morning fog burns off in the valley, she can walk out the front door and see a mountainous reminder of her father in the distance, a post-impressionistic monument to Diebenkorn’s way of looking at the world.

Split by the Russian River and painted over with vineyards that turn lush green every summer, fiery red and gold in autumn, and almost barren brown this time of year, Alexander Valley was the last place that had that effect on him.

For more information on the artist, visit the Richard Diebenkorn Foundation at diebenkorn.org.