Imagine taking an empty picture frame and laying it flat on a grassy meadow on the same day each spring. Inside that rectangle is a microcosm—a living, breathing universe unto itself. In the height of the season it might be buzzing with pollinators. A snake might slither past or a gopher might pop up. Filling the diorama, native grasses and wildflowers jockey for space with invasive species in a patchwork quilt of ground cover.

If you were to study the picture inside that frame, year after year, measuring how it changes and evolves, the data would unfold like a time-lapse video, charting the effects of extreme weather patterns, non-native plants, controlled grazing, and rampant wildfire—the real-time window into the local impacts of climate change.

In Sonoma County, we know intuitively that our landscape is changing. From one year to the next, we seesaw from extreme heat waves and drought to epic rains and floods. Call it climate change, call it global warming. As fires scorched our land, some call it life or death.

“The ‘change’ part in climate change is that we don’t know what’s coming. We just know it’s changing, and that makes it extremely difficult to predict what the effects are ~ researcher Sarah Gordon

But spring arrives, and the landscape regenerates. Some years, lupines and poppies in our meadows bloom weeks earlier than usual. Other years, migrating Canadian geese arrive later. After the Tubbs Fire, bright blue lazuli bunting songbirds appeared for the first time in years. Some seeds can lie dormant for decades, only triggered to germinate by fire.

Timing is everything. Humans invented clocks, but nature keeps its own calendar. Scientists call it “phenology,” the study of the timing of biological life cycles like flowering and mating and how those cycles are influenced by climate. From grasslands to wetlands, scientists fan out across Sonoma County, documenting its diverse ecosystems and their inhabitants.

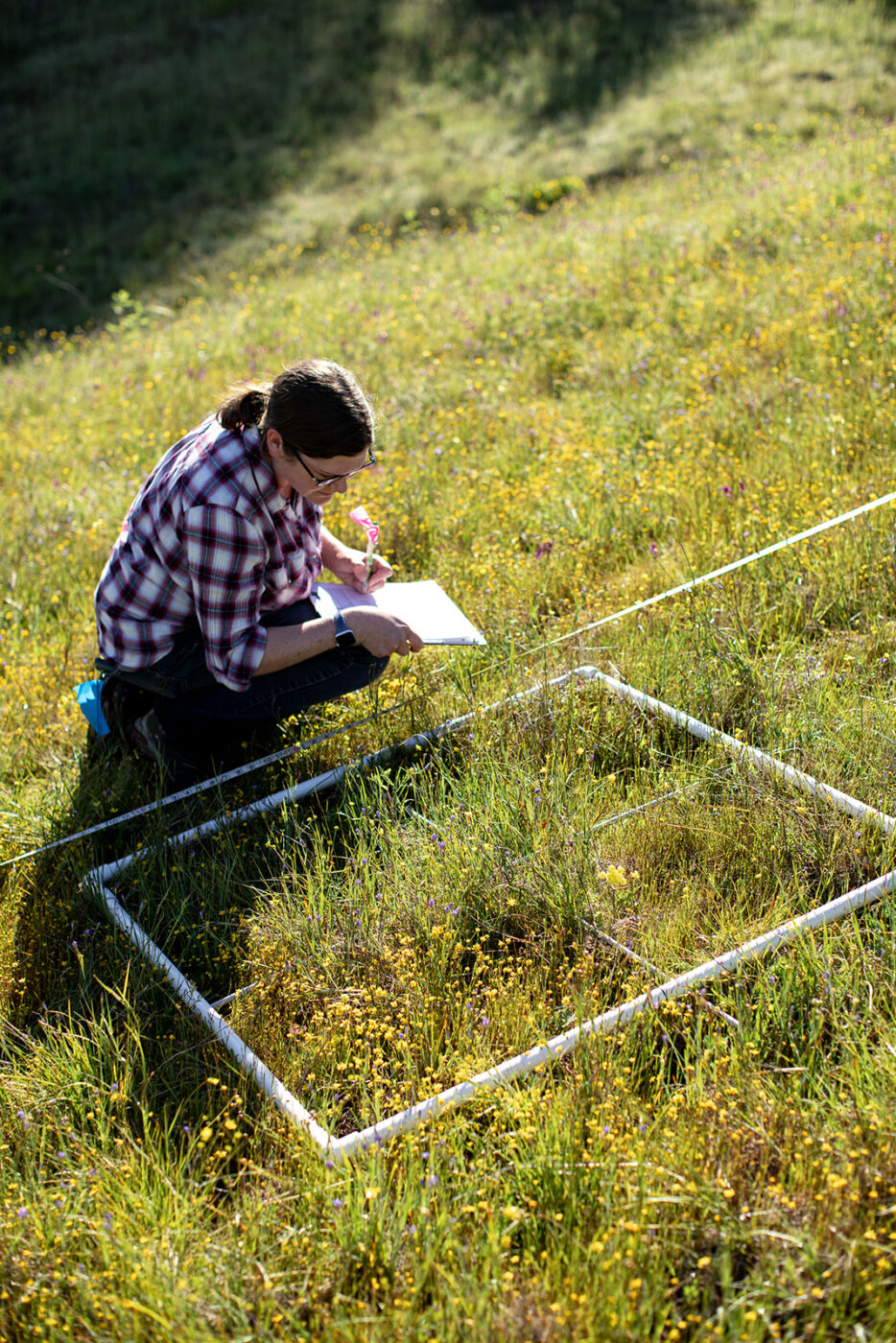

Every May at Pepperwood Preserve in the Mayacamas, researchers have been studying the same square-meter grassland plots, down to the centimeter, for the past 13 years. Instead of picture frames, they lay down white-tubed “quadrats” and measure the percentage of cover of native perennial grasses (California oatgrass, blue wildrye), invasive exotic annuals (barbed goatgrass, ripgut grass) and wildflowers (buttercups, native clover).

“If you look at every single vegetation map of Sonoma County, there will be many different forest types and shrub types, but when it comes to grasslands, it’s just listed as ‘grasslands.’ You know why? Because you can’t see it from space. You have to put your nose into it and really bend over to see it,” says Michelle Halbur, ecology research manager at the 3,200-acre preserve. “And what you see is incredibly diverse, on small and big spatial scales. Grasslands are very patchy. They’re dynamic over time, and they’re hard to categorize. They’re like the black box of vegetation types.”

In the Laguna de Santa Rosa watershed, plant ecologist Sarah Gordon studies vernal pools, the seasonal, swimming-pool-sized bodies of water that appear almost magically with the onset of winter rains and dry up by April or May, as part of a program started in 2006. These extremely fragile ecosystems are home to the endangered California tiger salamander and three endangered plants—Burke’s goldfields, Sonoma sunshine, and Sebastopol meadowfoam—which exist almost exclusively in Sonoma County.

On a recent morning, Gordon and a colleague set out with clipboards, making ripples across the pools in knee-high boots, to collect observational data, noting water depth and plant populations. Wading across one pool, Gordon spotted thin, green stems of Sonoma sunshine sprouting through the black mirrored water. A closer look revealed a string of tiger salamander eggs attached to a stem. Over the past few years, she’s witnessed “pretty extreme algal blooms” in the vernal pools, similar to toxic algae blooms on the Russian River, which can threaten fragile species.

“The ‘change’ part in climate change is that we don’t know what’s coming,” says Gordon. “We just know it’s changing, and that makes it extremely difficult to predict what the effects are going to be.”

This time of year, before the rolling hills of Sonoma County turn from Irish green to golden rye, students at Casa Grande High School in Petaluma flock to the school’s nursery to help repot seedlings. The seedlings will eventually find a home in restored grasslands as part of a program facilitated by Petaluma’s Point Blue Conservation Science. At Tolay Lake Regional Park outside Sonoma, students have helped restore over 4,000 plants.

Each year, as more extreme weather extreme weather conditions impact conditions impact the land, one of the questions researchers hope to answer is, how will the plants and animals respond? But in the same breath, they also want to know, how will our community respond?

Students also collect native grass seeds near future restoration sites. The seeds are brought back to the nursery to be weighed and catalogued. Then, depending on what kind of seed it is, they will encourage it to germinate—some seeds need to be roughed up and soaked in water or even dipped in acid to help break the seed coat. “There’s kind of a secret recipe for each species of seed,” explains Point Blue’s Isaiah Thalmayer.

If all goes well, by next spring Casa Grande students will repeat the ritual of replanting their carefully tended seedlings into larger pots.

But for now, students and researchers watch and learn. Each year, as more extreme weather conditions impact our grassland and wetland ecosystems, one of the questions they hope to answer is, how will plants and animals respond?

And in the same breath, they also want to know, how will our community respond?

Along the Laguna de Santa Rosa, the community seems up to the challenge. One Fulton area landowner had no idea what a vernal pool was when they purchased their property. At first, they were nervous about caring for endangered plants. But after a few years, “they changed the whole trajectory of what they are planning to do with their property,” says Gordon. “They installed fencing and brought conservation grazing onto the property, on their own time and on their own dime. They have done everything they can to help take care of these endangered plants.”

At Pepperwood, volunteer outings and forest and grassland workshops are offered several times a year. “We’re trying to help build the skill set so folks can go back to their own land, their own homes, and apply the work that we’re doing and the monitoring that we’re doing,” says Halbur.

“It’s important for the long term, not just because climate change is happening, but to ensure that we are always learning. We’re always asking of the land itself, how is it doing? Are we doing a good job?”

To learn more

Pepperwood Preserve: Wildflower tours and hikes each Saturday in April. pepperwoodpreserve.org

Point Blue Conservation Science: pointblue.org

Laguna de Santa Rosa Foundation: Spring ecology workshops in March and April. lagunafoundation.org