Winter is time for banana slugs to shine — literally — since wet conditions allow them to produce the mucus that is essential to their survival, explains Santa Rosa naturalist Sarah Reid.

“They need moisture to create slime, which they use for locomotion. It also protects them from dryness in soil and contains pheromones that attract other slugs for mating,” she says.

This “slime” or mucus is technically a liquid crystal, meaning its structure is more ordered than a liquid but less rigid than a solid. Slugs excrete sugar molecules and mucin proteins as dry granules that expand hundreds of times upon absorbing water.

During summer and fall, banana slugs may hunker down like a newt, trying to stay as cool and moist as possible. With winter rains and cooler temperatures, especially in our coastal forests but also on some inland slopes and ravines, more moisture at ground level means more banana slugs out feeding and mating.

“It’s their prime getting-together season,” Reid says. Enamored banana slugs will curl around one another like a yin-yang symbol, nibbling on each other’s bodies as they go. Then, from a hole in the top of their head called a genital pore, each will extend a penis — stay with us here — that can be as long as the slug itself. The dance and ensuing exchange of genetic material takes hours.

As anyone who heads out into banana slug habitat this time of year can quickly appreciate, there are a lot of slugs in the proverbial sea — but if they don’t successfully pair up, no worries, mate. Banana slugs possess both male and female parts (which explains the dueling phalluses) and can reproduce asexually. They lay clutches of 20 to 30 tiny, bead-size white eggs at a time. (Please save these factoids for friends and family on your next redwood hike.)

Another thing to know about banana slugs: They are not a single species, but rather six, inhabiting the West Coast of North America from San Diego to Alaska. All six can be found within California. Our local species, Ariolimax buttoni, has a yellowish-tan hue and can present with or without black spots — depending in part on dietary and environmental factors, Reid says.

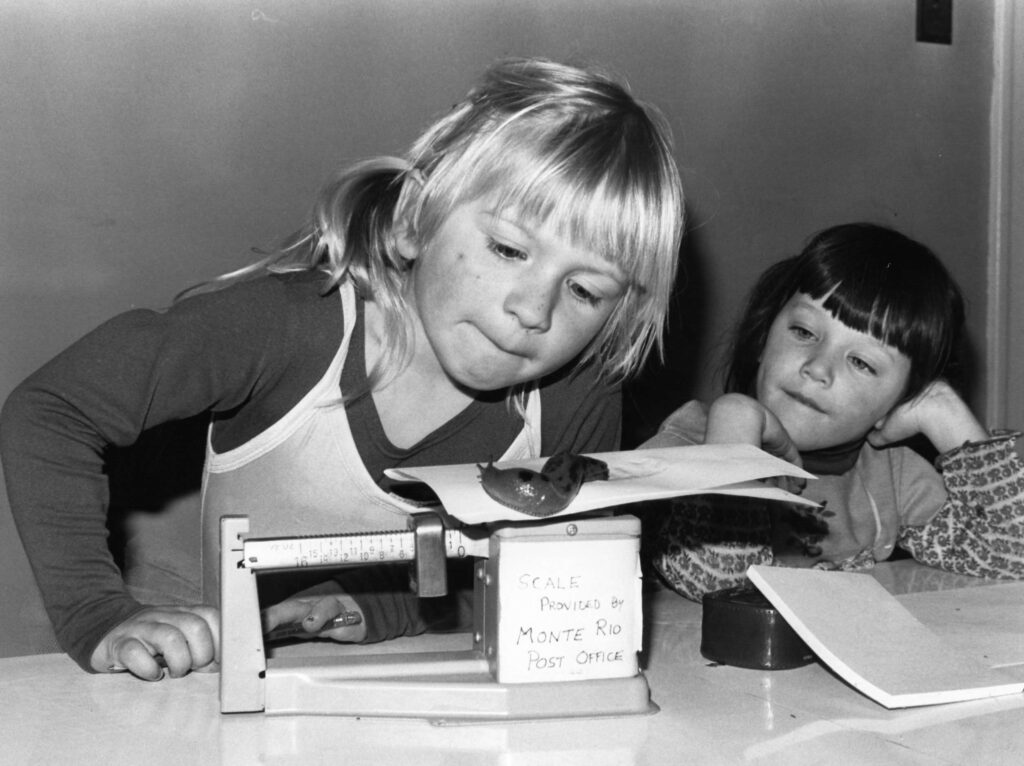

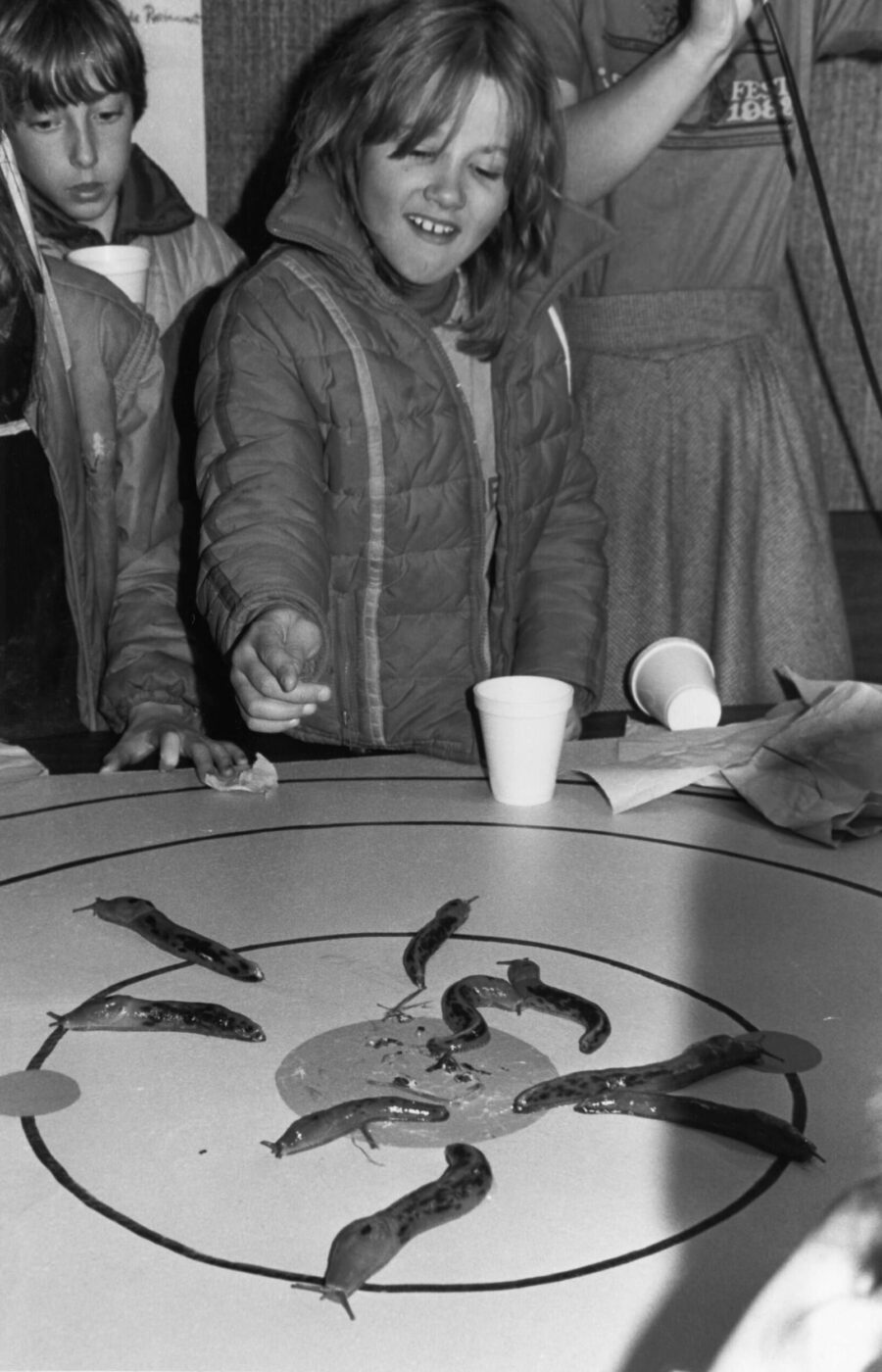

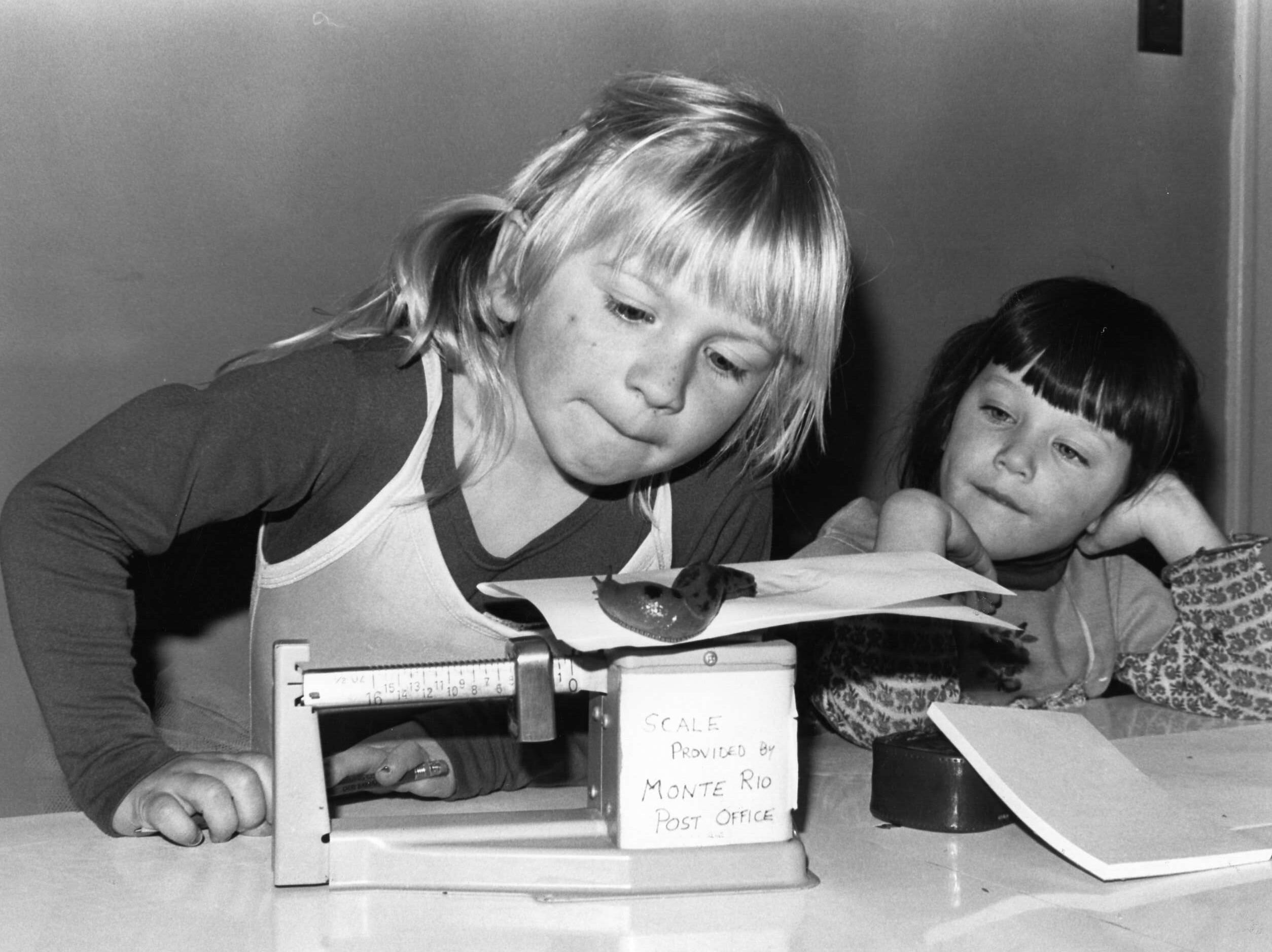

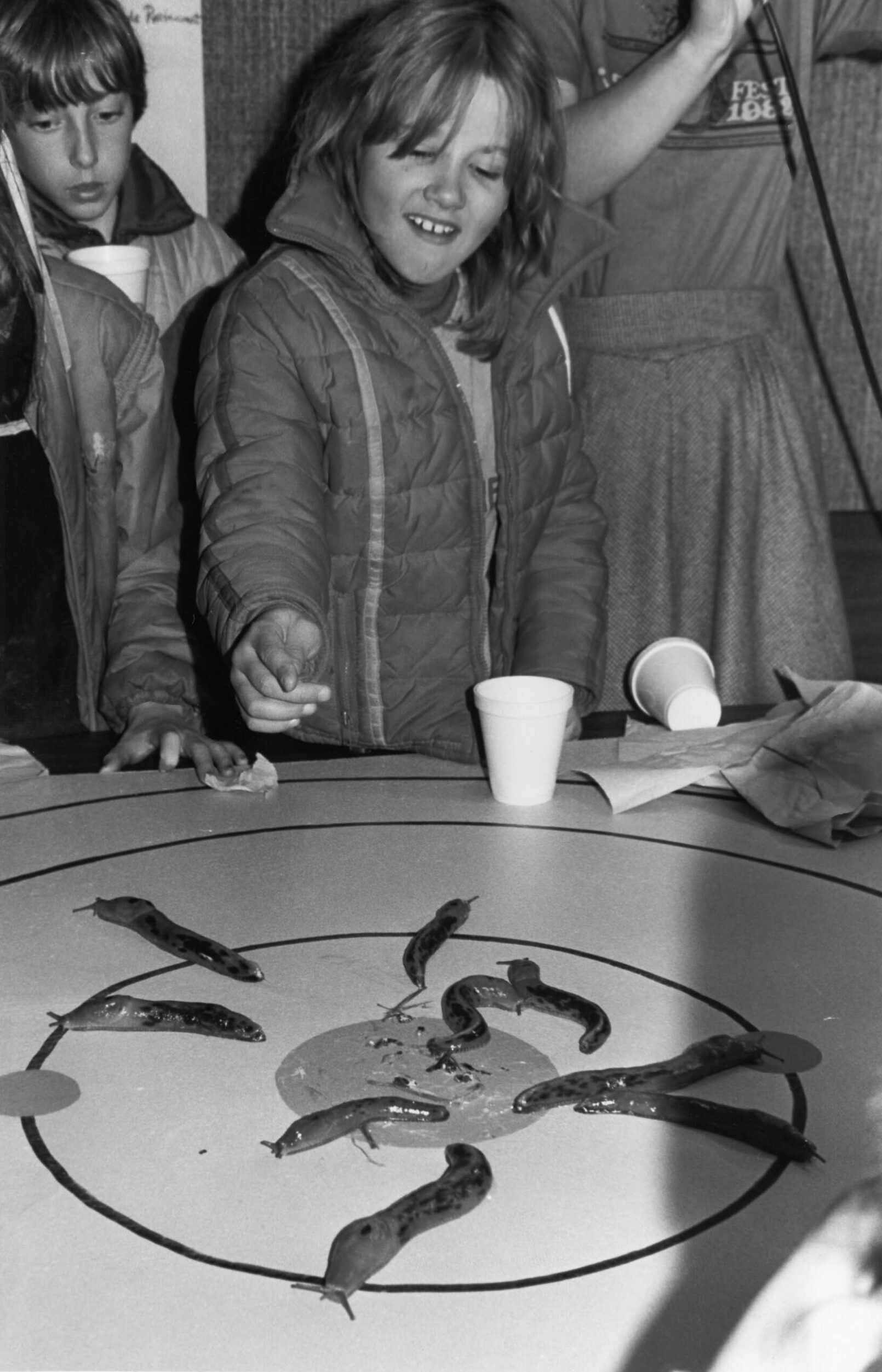

Sonoma County has celebrated the banana slug since well before it was named California’s state slug in 2024. From the early ’80s through 1991, Guerneville hosted Slug Fest, an event that featured slug races, a heaviest-slug contest, and a slug-cooking competition. Uncooked, banana slugs’ pheromone-laden slime-crystal is also an anesthetic, meaning it will make a predator’s tongue or throat go numb.

We recommend just letting them be and marveling at nature’s ingenuity.

Where to see banana slugs this winter

- Armstrong Redwoods State Natural Reserve

- Salt Point State Park (east of Highway 1)

- Trione-Annadel State Park (nearest Oakmont)

- Sonoma Coast State Park (along Willow Creek)