The Mattole Valley is almost heartbreaking in its beauty, a green and fertile vale along the pristine Mattole River, buttressed by the steep, dark and forested mountains of the King Range.

It is a long, arduous drive to the valley from the Highway 101 exit between the towns of Garberville and Rio Dell, the road narrow, potholed and punctuated by abrupt hairpin turns. The approach from the north, reached by driving south from Eureka and Ferndale, is even longer and more circuitous.

Isolation is perhaps the most salient characteristic of life in this part of Humboldt County, long shrouding the marijuana cultivation that is the engine of the regional economy. It has been that way for a generation, ever since the timber industry collapsed and Humboldt emerged — along with Mendocino and Trinity counties — as the notorious Emerald Triangle, the largest cannabis growing region in America.

When California voted in November to legalize recreational pot use, the industry stepped from the shadows with purpose. Its promise of short-term profit and long-term growth potential has triggered a “Green Rush” that will reshape the North Coast economy and upend the fortunes of growers.

Jessica Rockenbach and her partner, Kris Schuster, came to the Mattole Valley a decade ago and worked as tenant cannabis farmers. They saved their money, maintaining a frugal lifestyle that ultimately allowed them to buy a 60-acre parcel of gently rolling hillside land. It is here, in the heart of the Emerald Triangle, where the couple plan to realize their long-held dream. They’ll build a home, tend fruit trees, hike the woods, and fish for steelhead in the Mattole River. They are determined to spend their lives in this chosen place.

“It’s not going to be just a cannabis operation,” says Schuster. “That’s going to be a very small part of it, actually. We’re going to produce a broad range of organically grown crops. There’s an old orchard on the place, and we’re rehabilitating it. We plan to have a cidery. First and foremost, we see ourselves as stewards of this very special place.”

For years and for obvious reasons, Rockenbach and Schuster have lived and worked on the periphery of civil society. Cannabis cultivation existed in a legal gray area at best, pinned between a state that sanctioned medical pot 20 years ago and the federal government, which still considers the drug illegal in all cases. Though enforcement by government agents has been spotty in the Mattole Valley during the past decade, it was an omnipresent threat. The couple never knew if or when the black helicopters would descend, disgorging heavily armed officers in tactical gear intent on arresting them and confiscating their plants.

But that’s all changed through the combination of two landmark state laws. The first was passed by the Legislature and signed by Gov. Jerry Brown last year to regulate and tax medical cannabis. Then the second — Proposition 64, approved in November — legalized the recreational use of cannabis by adults.

For thousands of small pot growers like Rockenbach and Schuster — there are an estimated 3,000 alone in Sonoma County, gateway to the Emerald Triangle — California now comprises a bonafide business landscape free of the legal clouds that previously loomed over the state’s multibillion dollar pot industry. That sanctioned market is expected to quickly expand. By 2020, legal medical and recreational pot will generate $22 billion in economic activity — equivalent to two-thirds of the state’s retail wine sales — according to ArcView Market Research, an Oakland-based firm that studies the cannabis industry.

With such rich prospects for growth, a bevy of big investors based in New York, Chicago, Seattle and the Bay Area are hurrying to cash in on the new cannabis economy.

The contrast between such heavy money and Rockenbach and Schuster’s operation is stark, and the financial stakes for the couple are clear. Their vehicle is a battered Toyota 4×4 truck. They’re refurbishing an old sheet metal shack on their property for short-term living quarters. They plan to fell and mill some of the conifers on their land to build their home. With a go-ahead from state and county regulators, the duo will grow up to 15,000 square feet of marijuana in 2017 — the first crop under the new rules for their ultra-high-end enterprise, terravida farms.

While the couple’s plans are moderately ambitious by Mattole Valley standards, they’re nothing compared to those of the big players moving in. Under Proposition 64, no limits will be imposed on vertical integration, meaning a few huge operators could corner much if not most of the market. Opponents of Proposition 64 are thus haunted by the specter of gigantic Central Valley pot farms linked with wholesale and retail ventures, all of it pouring profits into the coffers of a corporate few at the direct expense of the existing small farmers and processors of Cannabis Country.

“Candidly, the future for many current growers isn’t bright,” said Joe Rogoway, a Santa Rosa attorney specializing in cannabis issues. “The new marketplace requires a degree of capitalization and sophistication that inevitably will leave people behind. It’s capitalism. There will be winners and losers.”

The transformation is already opening new agricultural and industrial sectors that are likely to have profound and far-ranging impacts on the state’s economy, environment and culture. Farflung communities like Garberville in Humboldt County that have flourished in the cannabis trade because of their isolation may find themselves edged out by places like Santa Rosa, with better access to capital, urban populations and a skilled, stable workforce.

“Most of California’s cannabis is produced on the North Coast,” said Tawnie Logan, the executive director of the Sonoma County Growers Alliance. “Mendocino, Humboldt and Trinity counties are the breadbasket. Then it moves south to major markets in the Bay Area and Los Angeles. Highway 101 handles a very large percentage of that traffic, and Santa Rosa is the logical capture point. We can handle not only growing, but processing and distribution. And I think we’re heading that way.”

In the Mattole Valley, Schuster and Rockenbach acknowledge the uncertainty they face. “We’re going to just have to wait and see,” Rockenbach said. “Frankly, we don’t know how it’s all going to play out, or what it’ll mean for us in the long run. Before, all we had to be was farmers. Now we have to be marketers, brand experts, designers, processing experts, and even lawyers to a degree. We’re dealing with issues we never faced before.”

The mood inside the old, ramshackle house that serves as the studio of radio station KMUD was not celebratory on election night. The FM station is based in Redway, a seven- minute drive north and west along the Eel River from Garberville, for decades a gritty redoubt of the region’s renegade pot economy. KMUD serves as a main information and entertainment source here, with hosts overseeing everything from lengthy Grateful Dead retrospectives to call-in shows on local politics. And on the evening of Nov. 8, the hosts and most of the callers were in shock.

By 10 p.m., Donald Trump had built up a lead in electoral votes that seemed certain to make him the next president of the United States, a result so unforeseen in this ultraliberal swath of the state that it had largely sidelined the evening’s other historic result — California voters’ overwhelming decision to legalize recreational pot.

“Where’s the bourbon? Did anybody bring bourbon?” howled one stunned KMUD staffer.

The three counties that form the Emerald Triangle have long existed as a promised land for the cultivation of high-grade bud. Marijuana is the economic foundation here, and Emerald Triangle cannabis is considered the ne plus ultra of the trade. Much of it is trafficked out of state and under Proposition 64, the market will only swell, possibly tripling the national trade in legal cannabis products. Twenty-six states now allow some mode of marijuana consumption, and in the November election, Massachusetts and Nevada followed California in sanctioning recreational use. Colorado, Washington and Oregon were first among the states to greenlight recreational pot use.

In the Emerald Triangle, thousands of small growers, many of them multigenerational cannabis families, serve as the backbone of the economy. And their general outlook explains why the reaction at KMUD to Proposition 64’s election night approval was muted at best. The law is widely seen as a threat as much as an opportunity, said Isabella Vanderheiden, one of the station’s two co-news directors. North Coast growers consider themselves producers of an artisanal product, said Vanderheiden, and Proposition 64 wasn’t necessarily written with their interests in mind.

“They’re small farmers, they’re independent, representatives of a unique culture,” Vanderheiden said. “Proposition 64 could easily change all that, shift the cannabis economy to corporate growers, distributors and processors. The people here feel they have a lot to lose.”

Proposition 64 will allow growers to emerge from the black market into a legal and regulated economy. That process had already begun with last year’s passage of the Medical Cannabis Regulation and Safety Act (MCRSA), which established detailed regulations for the expanded production, distribution and processing of medical marijuana. Under the still-evolving protocols of the MCRSA, farmers — like Rockenbach and Schuster — who bring their operations into compliance can grow their product openly and sell it to distributors for a fair and stable price.

But for growers, that takes money, — often hefty amounts — to build proper water systems, shore up roads, roll out safeguards for workers, curb erosion, and comply with rules for pesticide use and organic certification.

“They’ve also been adjusting to the reality of taxes,” said Sydney Morrone, a KMUD news director. “Under the MCRSA, substantial taxes can be imposed by the counties. But they also have to deal with income taxes. For decades, people haven’t been paying direct state or federal income taxes on their cannabis. They may pay taxes indirectly — many of the businesses here were started and are supported by cannabis money. But they haven’t paid on their crops. Now that’s changing. If your operation is compliant, you will pay income takes.”

Similar government regulation and taxation will occur under Proposition 64, meaning rules for medical and recreational pot will exist on twin tracks for the foreseeable future.

The result is certain to trigger a fundamental economic and cultural shift in the marijuana industry, and especially in the Emerald Triangle, where money generated by the off-books pot trade supports Main Street businesses and nonprofit groups and has even underwritten political campaigns.

In Garberville, businesses along the main drag have long functioned, purposely or not, as cash laundromats for the marijuana economy.

The town of fewer than 1,000 full-time residents bears the marks of a love-hate relationship with the pot culture and workforce that sustains it. The community has become an international magnet for the seasonal workers or “trimmigrants” who flock to the Emerald Triangle each harvest season, looking for employment processing dried flowers. Others are simply here to smoke as much dope as possible and squat on the street with newfound friends, playing guitars, often poorly. They are tolerated, but barely. A sign on the window of the Blue Room Lounge features a marijuana leaf in a circle and a slash mark through it with the words, “No Work Here — Move On,” and another sign on the door declares, “Absolutely No Patchouli.”

“The people who live here, they want to have their cake and eat it too,” said a man in his 40s with slicked-back hair who identified himself as Richard. He was standing on the street with an acquaintance, another longtime Humboldt County resident who was dressed in a trench coat, shirt and tie, holding up a copy of The Watchtower.

“They created this situation, but then they get upset with all the homeless kids here, sucking off society,” said Richard. “And at this point, it’s too late to change. And that has a lot of people worried, because there’s nothing else. Also, no one knows what full legalization will bring.”

“It [marijuana] does support this county, that’s a fact,” said the Jehovah’s Witness, who declined to give his name. “I’ve lived here for 40 years. Several of the businesses on this street are owned by one guy, a grower, a millionaire. A lot of the retired people here, they grow some plants to make ends meet.”

But there are no guarantees the storefronts will remain open once cannabis is regulated and taxed, so residents and merchants here and throughout the Emerald Triangle find themselves in an economic limbo.

“The California cannabis industry consists of 60,000 independent business people,” said Hezekiah Allen, executive director of the California Growers Association, which lobbies on behalf of marijuana cultivators. “About 50,000 are growers and 10,000 are retailers, manufacturers or own support enterprises. We provide well-paying jobs in small communities. But some folks want massive wealth. They look on us as an inefficient industry that needs to be captured.” Recent history provides a cautionary tale for the cannabis industry, Allen said.

“We saw the mindset that’s playing out now with another North Coast resource-based industry. Pacific Lumber was a sustainablyoperated redwood company. Then Charles Hurwitz took it over, determined to liquidate the resource. We’re still suffering the effects of that tragedy. Rural communities have a hard time asserting themselves under these kinds of pressures. Cannabis provides California with the opportunity to create a multibillion dollar sustainable marketplace. But we have to be careful about our choices — industrial agriculture and sustainable agriculture are mutually exclusive.”

If Garberville is Old Cannabis, a rural North Coast community that always has relied on natural resources — first timber, now pot — to survive, then Santa Rosa is emerging as the New Cannabis hub: a sizable, economically diversified, strategically located city, with a robust private sector, abundant capital, good infrastructure and skilled workforce.

Sonoma County already supports about 9,000 marijuana-associated businesses, according to the New York Times, and with Proposition 64, that figure inevitably will grow.

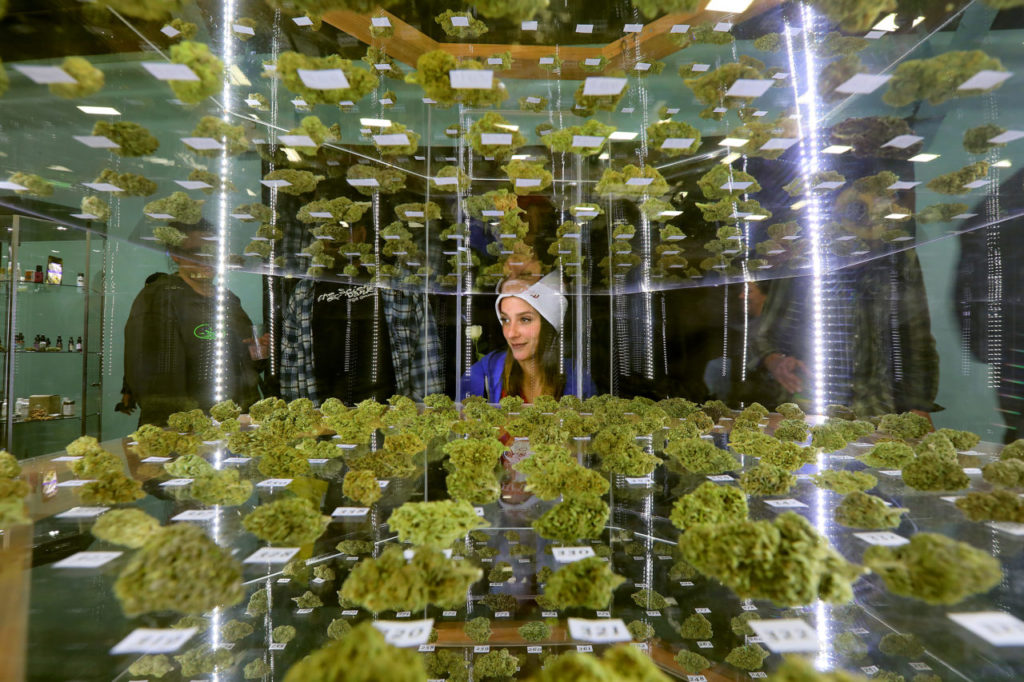

Those with an early foothold include entrepreneur Dona Frank, who opened one of the county’s first dispensaries, OrganicCann, and now runs a veritable empire of cannabis-associated enterprises, including multiple dispensaries stretching from Oakland to Hopland and a distribution company that offers members a wide choice of exotic marijuana strains from Emerald Triangle growers. She has built a loyal customer base through direct marketing, including a quarterly community-supported agriculture box, a farmers market and collaboration on product lines with celebrities ranging from international hip-hop artists to porn stars.

“I have been following the winery model for eight or nine years,” Frank told The Press Democrat a week before the vote on Proposition 64, which she supported.

Others looking to set up shop include Privateer Holdings, a Seattle private equity firm with principals that include Silicon Valley venture capital superstar Peter Thiele. It picked Santa Rosa as the headquarters for its expansion into California’s cannabis market, with plans, approved by the city, to manufacture, process and distribute a line of bud varieties, hemp-oil body-care products and smoking materials dubbed Marley Natural.

Another figure drawing notice is Ted Simpkins, the founder of Sonoma County’s Lancaster Estate winery and the former CEO of Southern Wine & Spirits, the nation’s largest wine and liquor distributor. Simpkins, who owns a home off Chalk Hill Road in Healdsburg, recently established River Collective, a cannabis distribution firm based in Sacramento.

Simpkins has played an active role behind the scenes in shaping the distribution plan favored by the state’s taxing authorities under last year’s medical marijuana law. According to a report by the Los Angeles Times, he pushed successfully for the model used in the alcohol industry, with growers dependent on distributors to sell their product. Many veteran North Coast growers opposed the policy, concerned that it will strip them of both autonomy and revenues.

“The larger growers in particular didn’t like the distribution clause,” said Allen of the California Growers Association. “They feel they can do better on their own.”

Simpkins did not respond to interview requests. But Rockenbach and Schuster are among those who favor his involvement, saying they’re eager to work with partners, especially savvy and well-funded distributors who can help them gain a foothold in the increasingly competitive market.

“People like Ted can really help us develop our brands, establish market share, and provide growers with stable and fair prices,” said Rockenbach. “As it stands, we’re completely at the mercy of the [medical marijuana] dispensaries. They exploit growers as a matter of course. We recently were guaranteed a price of $1,500 for some of our product. It was top-grade, organic flowers produced under best environmental practices. But when we delivered, we were told we’d only get $1,000 a pound. When we complained, the owner told us that he had ‘10 Mexicans’ a day coming in, offering to sell at $500 a pound, so take it or leave it.”

Like many cannabis farmers, Rockenbach and Schuster are leery of Proposition 64, worried that it will allow big players to consolidate all sectors of the trade — cultivation, processing, transportation, secondary product manufacturing and retail sales — driving out all smaller stakeholders. They’re also worried about something else: the incoming Trump administration.

Some of Trump’s cabinet selections are eliciting particularly sharp fears on the North Coast. Alabama Sen. Jeff Sessions, Trump’s nominee for attorney general, is deeply problematic for legalized cannabis advocates. During a Senate hearing earlier this year, Sessions called cannabis “a very real danger,” and declared that it shouldn’t be legalized.

“The day before the election we were optimistic, certain that we’d have no major problems from the federal government,” said Schuster. “Now? We just don’t know. We don’t know what Trump will do. But we’ve already committed. We filed all the paperwork. We’ve on the record. So we can only move forward.”

But Rogoway, for his part, remains moderately optimistic about Trump.

“He’s indicated he wants to leave it to the states, and he has made some supportive comments about medical marijuana,” said Rogoway. “Further, [Silicon Valley venture capitalist] Peter Thiele has Trump’s ear, and he’s a principle in Privateer Holdings, one of the biggest cannabis hedge funds. So I don’t anticipate a major disruption from the federal side. We are advising our clients to stay calm, don’t panic and proceed with compliance.”

They were just a snapshot in time, but the satellite images of several North Coast watersheds beamed back to state water and wildlife scientists in 2012 shocked even veteran regulators of the cannabis trade.

Hundreds of marijuana farms had popped up in places they had never been, or never been detected. In graphics produced from the satellite data, they showed up as dots — red for outdoor gardens, green for greenhouses — and in places they covered the blue lines demarcating streams for miles.

The records were evidence of a sharp increase in pot cultivation that scientists said poses a serious threat to imperiled salmon and steelhead runs, the North Coast’s original, natural bounty. In the teeth of California’s historic drought, water consumption by pot farms could effectively stanch the seasonal flow of many small creeks in the region, leaving young fish stranded.

“Essentially, marijuana can consume all the water. Every bit of it,” Scott Bauer, a state Fish and Wildlife senior scientist, told The Press Democrat at the time.

Stormer Feiler, a State Water Quality Control Board environmental scientist who participated in the same multiagency study, notes that any citizen can get a sense of the problem from a computer or smartphone.

“Just go on Google Earth and look at, say, southern Trinity County,” Feiler said. “It’s a patchwork of marijuana plots. We estimate there may be 50,000 grow sites in California. We’re seeing massive erosion from illegally graded roads. We’re seeing streams drying up and salmon and steelhead dying. The watershed impacts from marijuana cultivation are huge. We’re doing what we can, and along with other state and federal agencies and the counties, we’ll enforce the new regulations. But we all have limited staff. Right now, (the Water Board) is dealing with about 800 cultivation permits for the North Coast, and that number is only going to grow. So our job is going to stay pretty challenging for a while.”

Increasingly, both regulators and compliant farmers agree on the necessity of reining in the guerrilla cultivators growing on public land or operating irresponsibly on private land. Such enterprises are widely blamed for the massive environmental impacts associated with the industry.

Mattole Valley residents have long been terrorized by federal and state agents swooping in on helicopters to raid pot farms, said Kris Schuster, but landed growers may welcome such operations on neighboring public lands as private farms move toward compliance.

“No one who is a legitimate member of our community likes the [guerrilla] growers,” Schuster said. “Some of them are armed. They contaminate our water supplies and kill our wildlife. We’ll be glad when they’re gone.”

But it’s not going to be easy to bring the farmers yearning to be legal into environmental compliance, let alone the growers who are determined to remain outlaws. There aren’t enough regulators, and there are far too many pot plots.

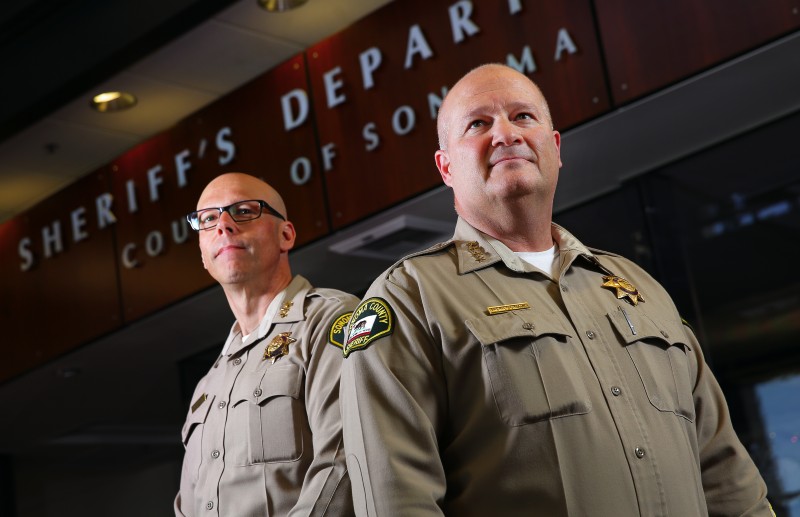

Furthermore, a legal market is unlikely to end certain malignant issues associated with the cannabis trade. Like violence. That’s the main concern of Sonoma County Sheriff Steve Freitas, who observed the North Coast has witnessed some particularly horrendous cannabis-associated crimes in recent years.

“A grower just was murdered near Willits,” said Freitas, a bald, powerfully built man of middle height who assays the world with the flat, unwavering gaze of the veteran lawman. “In October, there was a double murder in Sebastopol that was marijuana related. And we had a triple murder near Forestville in 2013 when a marijuana deal went bad.”

Such incidents can be expected, said Freitas, as long as marijuana is legal in some states and illegal in others. The states where cannabis is illegal function as a kind of regulatory low pressure area, drawing in large quantities of high-grade weed from the legal states.

“In basic terms, people can get more money for marijuana in areas where it remains illegal, so a lot of legally produced marijuana inevitably will find its way to illegal markets,” Freitas said. “That brings bad guys here to Sonoma County and the North Coast, where it’s produced. All of the murder cases I just cited involved perpetrators from out-of-state. And I don’t think that’s going to change unless or until we see marijuana legalized and regulated at the federal level.”

The conceit that cannabis use is universally benign also is faulty, said Robert Giordano, a Sonoma County assistant sheriff who recently traveled to Colorado to assess the impacts of recreational cannabis legalization in that state. Giordano said the Colorado state poison control center received 400 calls on marijuana-induced psychosis since pot was declared legal, a sobering figure considering the agency fielded no such calls for the five years preceding legalization.

“The main problem is the edible products, and the extracts like ‘wax’ and ‘shatter,’” said Giordano. “It’s hard to control the doses with edibles and the extracts are astronomically high in THC. You can get an extremely large dose with a puff or two, much, much more than you could by smoking dried flowers.”

Still, Proposition 64 is now state law, and Freitas confirms he and his fellow officers will uphold it.

“I think this department will back totally away from enforcement in regard to marijuana” as long as other crimes are not involved, said Freitas. “Our role will be more administrative — making sure regulations are implemented properly, that permits are in order, and so forth.”

Even the legislators who helped reform some of California’s cannabis laws are less than enthusiastic about Proposition 64.

“Smaller growers are very concerned about the license category that allows grows of unlimited size in five years,” said Assemblyman Jim Wood (D-Healdsburg), a co-author of the MCRSA. “When we crafted the MCRSA, we adopted measures to ensure that larger players couldn’t grab multiple licenses, and get bigger and bigger. Proposition 64 just kind of throws that out the window.”

But like Freitas, Wood has adjusted to the consequences of Nov. 8.

“I didn’t support Proposition 64, but it’s now up to the Legislature and proponents to ensure that the intent of the proposition is [upheld],” he said. “There will be challenges and unintended consequences, so it’s really important that we all work together to solve those issues as they [develop].”

Among cannabis cultivators, Jennifer Bruce’s stance on Proposition 64 puts her in the clear minority. She supported the ballot initiative. She believes medical marijuana isn’t sufficient to assure a stable cannabis trade, one that’s large enough to support California’s 50,000 cultivators. To survive, she says, small farmers must get behind a regulated recreational market.

“Is [Proposition 64] perfect? No,” said Bruce, who has been cultivating cannabis for about 20 years in Arcata, on the Humboldt Coast. “But it’s at least a start, and it gives people an opportunity to become part of a new industry in new ways.”

Bruce said she “still grows some flowers,” but she is shifting her focus from smokables to edibles. Her appetizing and decidedly psychoactive treats took two first-place prizes at the 2016 Hempcon, which bills itself as the nation’s largest marijuana convention-cumfestival. She has invested heavily in equipment to produce and package her goodies — marketed under the brand name Sarkara —and is entertaining offers from venture capitalists.

“I’m a single mother, so it’s a way for me to ensure a secure future for my family,” said Bruce, “but I support Proposition 64 for reasons other than personal opportunity. I know most people up here oppose [it] because they want to maintain exclusivity, which they think helps maintain decent prices. There’s something to that. But this is also a social justice issue. I want to be able to provide good living wages for the people who work for me, and I can only do that with a thriving legal business. And people still go to jail and prison for cannabis, especially people of color. The only way we’re going to really stop incarceration is with a fully legal marketplace.”

While some aspects of Proposition 64 kicked in immediately after passage — it is now legal for adults to possess an ounce of dried flowers or eight grams of concentrate and grow up to six plants — recreational cannabis outlets won’t appear until at least 2018. But it’s all coming: ambitious indoor and outdoor grows, certainly, but also edibles and extract processors, perhaps even bud pubs and organized tours of Cannabis Country. And it’s not just a matter of psychoactive cannabis. Hemp — low-THC cannabis variants that provide superb textile fiber and valuable seed oil — also has tremendous commercial potential, said Craig Litwin, a cannabis industry consultant and former Sebastopol mayor.

“It yields high-quality cloth and paper, the seed can be used for food oil and animal feed or processed for fuel and solvents, it doesn’t require pesticides, and its cultivation would work against deforestation,” said Litwin. “It’s an untold part of the cannabis story, but it could ultimately be worth billions.”

Logan, the Sonoma County cannabis advocate, said Sonoma’s carefully cultivated sustainability ethos should serve the emerging legal trade well. The county has adopted rigorous regulations that will require all indoor growers to purchase energy from sustainable sources, and environmental compliance for outdoor grows and manufacturing enterprises will also be strictly enforced.

“That may seem like a burden to some businesses, but it’s also a powerful branding tool,” said Logan. “If you have, say, stamps on your cannabis confirming that it’s from Sonoma and that it’s produced by solar power and that it’s salmon-safe, you automatically appeal to a large segment of consumers.”

Still, Logan is no starry-eyed Pollyanna, convinced all will go well simply because the cause is just.

“Industrialization and consolidation are inevitable,” she said. “It can all be done sustainably, and it can be done equitably. But it’s going to take a lot of work. For example, we’re helping small farmers form co-ops. We think that’s the only way they’ll be able to survive with the big money coming in. We’re only going to have one chance to get this right, and we need to proceed carefully.”

Back in the Mattole Valley, Schuster and Rockenbach are doing everything possible to get it right. They’ve filed for the necessary permits, and they’re spending a lot of money to bring their operation into compliance. They’re designing logos and packaging for their products, and they’re developing cannabis strains uniquely suited to the valley’s microclimates.

If they’re concerned they could still be undone by government and market machinations beyond their control, they’re tamping down their fears, showing visitors nothing more than a steely resolve to persevere. Come hell, high water, or a return of the black helicopters, they’re not leaving their verdant home.

“We’re not in the Mattole Valley to grow cannabis,” says Rockenbach. “We’re growing cannabis so we can live in the Mattole Valley.”

California’s Path to Legalized Pot

More than 60 percent of Americans now support legal cannabis, a trend that began 20 years ago with the passage of California’s Proposition 215, the country’s first medical marijuana initiative. California was a cannabis policy outlier back in 1996, but now legal pot — medical and recreational — is a social and economic juggernaut. Colorado and Washington both approved legalized recreational marijuana in 2012, and California reasserted itself as the leader in legal weed with the passage of Proposition 64. The state has the agricultural base, the industrial and marketing infrastructure and the workforce needed to supply branded, top-quality cannabis products to the nation — and ultimately, the world.

Currently, legal cannabis in California is governed by two different laws. The Medical Cannabis Regulatory and Safety Act addresses the use of cannabis by people with a physician’s recommendation, while Proposition 64 pertains to adult recreational use. Requirements for cultivation and distribution differ for each law, and there may be compliance conflicts for producers and administrative difficulties for regulators as they try to reconcile the different statutes. Major differences between the MCRSA and Proposition 64 include the size of sanctioned operations. The MCRSA caps the size of outdoor grows at 1 acre and indoor grows at 22,000 square feet. Proposition 64, on the other hand, authorizes various levels of cultivation under a tiered and timed system, concluding with permits that will allow operations of any size in five years.

The MCRSA also stipulates that growers must sell their products to distributors, but generally forbids vertical integration: You can be a grower, or a distributor, or a processor, but you can’t be all three. Proposition 64 doesn’t require growers to sell to distributors and allows cannabis entrepreneurs to wear multiple hats. If they have the requisite ambition and capital, they can grow pot, distribute it, process it, test it and sell it retail.

If there are risks to the legalized cannabis trade, there could also be significant social benefits. A 2016 analysis from ArcView Market Research estimates legal medical and recreational pot will generate $22 billion in economic activity by 2020, and a lot of agencies and public service organizations will be in line for the tax revenues those sales will generate. Under Proposition 64, about $450 million could go annually toward funding youth drug avoidance and treatment programs; $150 million could be devoted to the California Highway Patrol, local law enforcement and fire response programs and public health initiatives; another $150 million would be used to remediate waterways damaged by cannabis operations and protect public lands from illegal growing activities; and $25 million would support ancillary education, law enforcement and health programs.