The city of Healdsburg is often cast as the symbol of Wine Country, with a culture of hospitality revolving around its scenic vineyards and upscale dining. But this summer, its residents learned that narrow-mindedness and racism can fester— even in a diverse community that has always considered itself progressive.

Writer Austin Murphy looks back at five weeks of turmoil that rocked the town to the core and the ways residents are trying to move forward.

If the brochures are correct and Healdsburg is the heart of Wine Country, the heart of that heart is the town’s park-like plaza, an Elysian oasis of redwoods, cedars and Canary Island date palms.

The centerpiece of the plaza is a handsome, copper-roofed gazebo that served, before Covid-19, as a bandstand for Healdsburg’s “Tuesdays in the Plaza” summer concert series. While there were no concerts in the square this summer, there was plenty of drama.

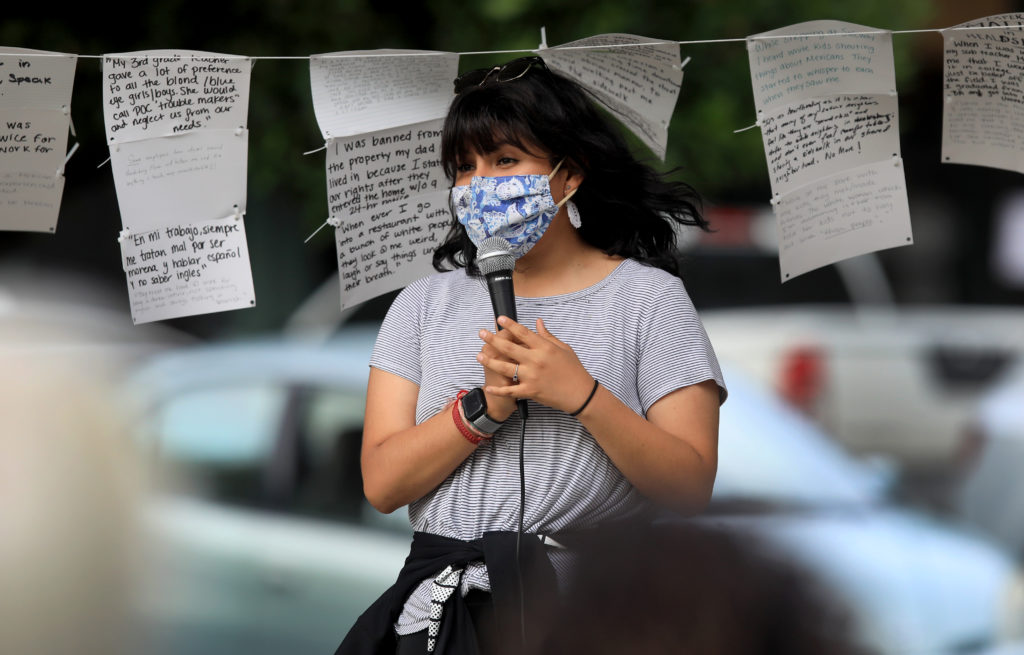

On the afternoon of June 11, strings were tied between the gazebo’s pillars. From those strings hung scores of white rectangles, like little sheets on a clothesline.

Were they Tibetan prayer flags? Apartment listings? Missing pet alerts?

They were, in fact, a city’s dirty laundry, fluttering in the breeze for all to see.

This was 17 days after George Floyd had been killed in the custody of Minneapolis police. The civil unrest sparked by his death convulsed the nation and found its way to this city of 12,000, where 30% of the residents identify as Hispanic. The words on those pieces of paper in the gazebo served as pointed reminders that, yes, racism can flourish even in picturesque towns that consider themselves progressive.

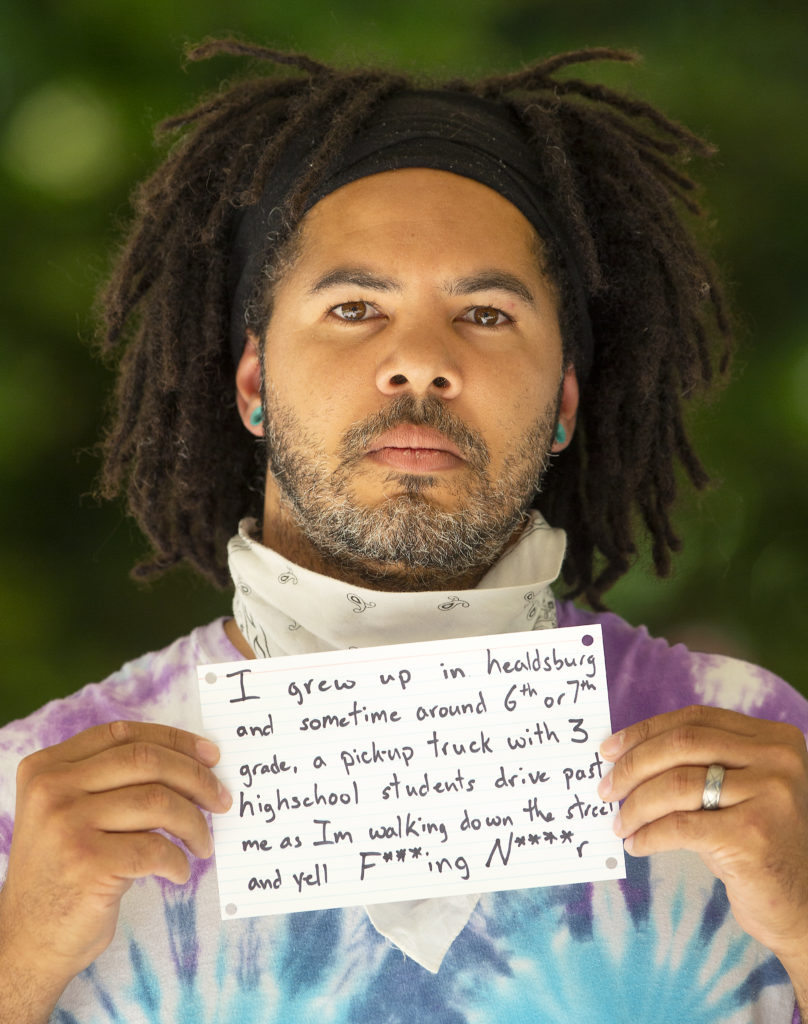

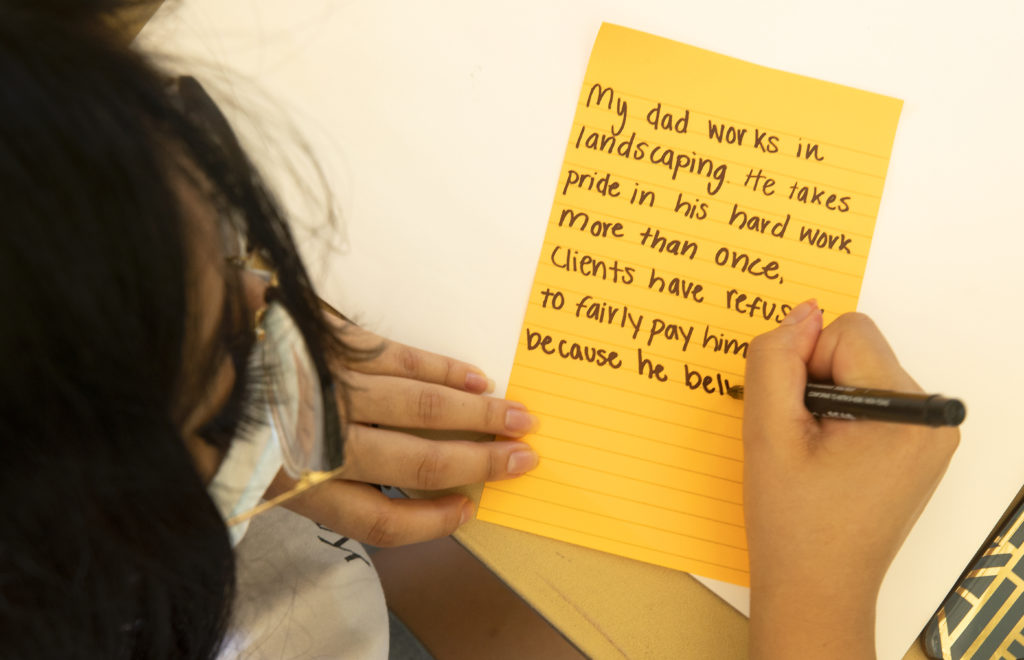

“I don’t want my kid in that Mexican teacher’s class” – statement from white parent to principal during meeting with Latina educator “I grew up in Healdsburg and sometime around 6th or 7th grade a pickup truck with three high school students drove past me as I’m walking down the street and yell ‘F—-g n—–!’” “Go back to where you came from.”

“This white girl told me I would look ‘prettier’ if I straightened my hair more often. F— your Eurocentric beauty standards.”

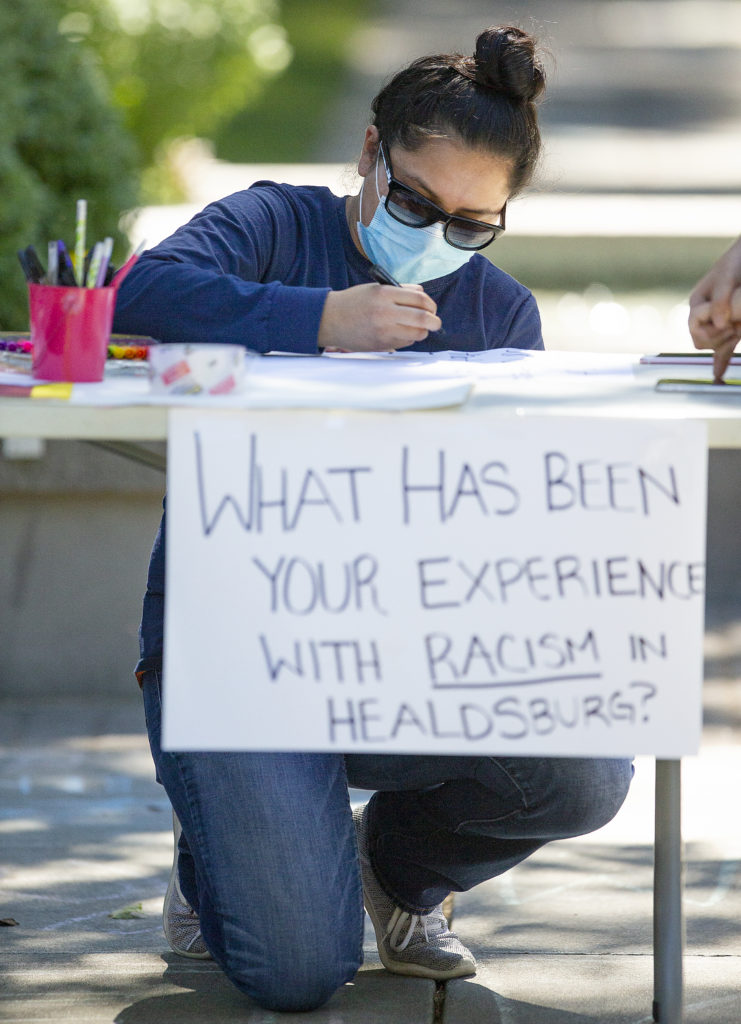

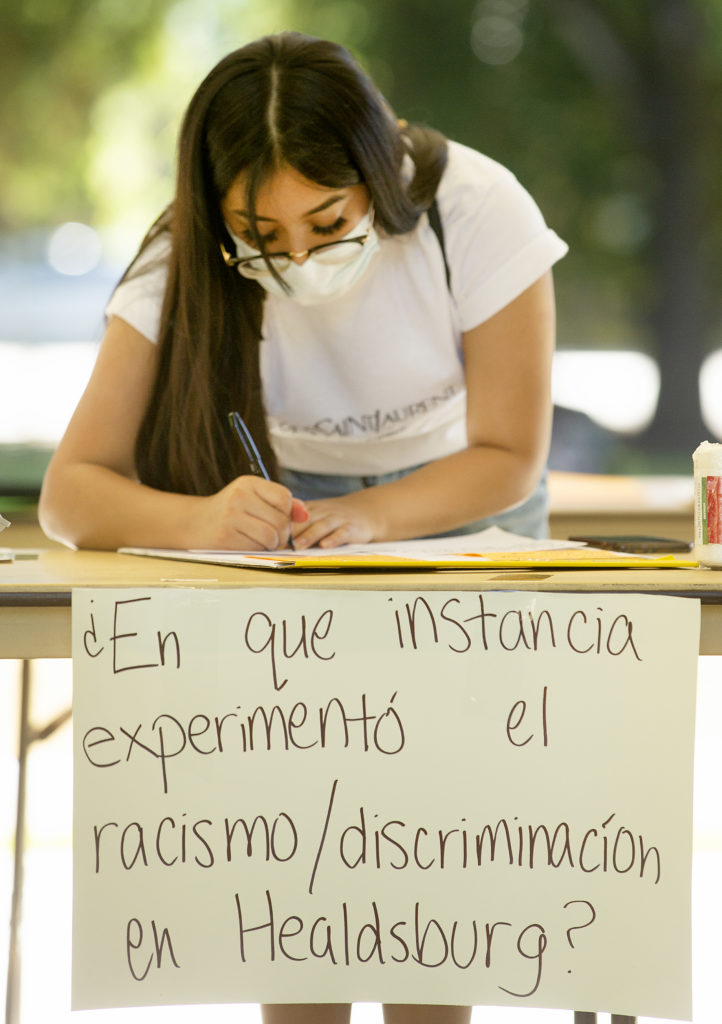

These accounts of racism were part of an art installation conceived by Cristal Perez and Lupe Lopez, Latinx women and recent graduates of Healdsburg High School. Perez, 20, is a criminology and criminal justice major at Sonoma State University. Lopez, 22, recently earned her degree in sociology at San Francisco State University, and is now a graduate student at Columbia University.

Both were frustrated and disheartened by what Lopez described as “tone-deaf ” comments made by members of the city council in early June. So they cast a wide net on social media, inviting people to share their experiences of racism in Healdsburg.

They got over a hundred. “It was very overwhelming,” said Perez. Those searing responses, on public display in the plaza, shed uncomfortable light on what truly stood at the center of the town. The fragments of injustice blew on slips in the breeze, painful testaments to incidents of white privilege and insidious racism, urging Healdsburg to examine itself.

The five weeks that shook Healdsburg to its core came to a head the night Perez and Lopez debuted their display on the plaza. A protest was planned to coincide with the installation, and hundreds of people showed up. By the end of the evening, what began as a civil exercise had boiled over into a most un-Healdsburg-like display of shouts, recriminations, and anger directed at the town’s 64-year-old mayor, Leah Gold.

Ten days earlier, in the third hour of a Zoom meeting of the city council, Gold had casually dismissed a fellow council member’s attempt to schedule a discussion of the Healdsburg Police Department’s use-of-force policies.

His rebuffed request came as communities across the nation questioned themselves following Floyd’s death. Black Lives Matter protests were sweeping the country. Gold and the four council members who had agreed with her quickly reaped the whirlwind, finding themselves castigated on social media for their alleged blindness to systemic racism and their own white privilege.

That night, Gold stood in the plaza, attempting to explain herself to vocal critics – many of whom had, presumably, voted for her. Now they drowned out the movement’s familiar chant of “No justice, no peace!” with calls for Gold’s resignation.

“I’ve lived here all my life,” said Tomas Morales, one of several people of color who confronted the mayor that evening. “For somebody to be so blind and be in a leadership role of this town is just ridiculous.”

It mattered little to Morales and the growing cohort of Gold critics that the mayor never claimed that racism does not exist in Healdsburg. In the Zoom meeting, she was clearly addressing the narrower subject of the town’s police department.

The protestors were angry, and now they’d found a visible – some would say convenient – target for that anger.

“This town was built on the backs of Mexican farmers,” Morales added. “It’s one thing for people to know us as this little wine destination, tourist, yuppie town, but it’s another for our leadership to…be so blind to what’s always been here.”

Strong-willed and proud of the progressive record she’d compiled during her two terms on the council, Gold underestimated the depth of public outrage. “What’s happening in America right now,” said Ariel Kelley, the CEO of Corazon Healdsburg, who is running for city council in November’s election, “is that a lot of young people are saying ‘Enough is enough. This is our moment.’”

For misjudging that moment, Gold was heaped with criticism that showed no signs of abating. And so, on June 16, the mayor announced that she would resign, to better enable the council “to address these issues of racial equity.” Seeing that she had become “a target,” Gold explained, “they may be more effective if I’m out of the picture.”

“I don’t really need this in my life,” she added, in a less guarded moment.

While Evelyn Mitchell succeeded her as mayor, Gold’s place on the city council was taken by the businessman Ozzy Jimenez, who became just the third Latino council member in the city’s 153-year history, the first in nearly three decades.

“That’s unacceptable,” said State Senator Mike McGuire, D-Healdsburg, of the city’s glaring lack of people of color in positions of power. He described the appointment of Jimenez as “a game changer.”

A month after Gold’s resignation, McGuire did not exactly leap to her defense when given the chance.

“Look, I’ve worked with Leah Gold for many years, and I’m grateful for her dedication to the community,” said McGuire, who grew up in the city, whose family has been there for three generations, and who was once Healdsburg’s youngest mayor.

“But it’s clear there is systemic racism in Healdsburg.”

“This community, like thousands of small towns and big cities across America, is demanding change. And it’s change that has taken too damn long to take hold.

“The reason this has had such lasting power,” he said, referring to the Black Lives Matter movement, “is that it’s coming from the streets up.”The protests have sent “the clear message that we can no longer accept systemic racism and politics as usual.

“We can’t miss this moment. We can’t miss it.”

The initial controversy started at a run-of-the-mill city council meeting on June 1. Council member Joe Naujokas, invited to chime in on “matters of interest,” shared that that he’d been getting feedback from constituents on “the events in Minnesota.”

Floyd had died six days earlier. Demonstrations were sweeping the nation and the Bay Area. Fifteen miles down Highway 101, police were bracing for a third straight night of protests in Santa Rosa, which was under an 8 p.m. curfew. “Given the circumstances we’re seeing around the country,” Naujokas told his colleagues, “a full conversation” on the Healdsburg Police Department’s use-of-force policies seemed in order. He asked that discussion to be put on the agenda for the council’s next meeting.

“Honest to God,” said Naujokas, six weeks and one mayor later, “I thought it was going to be a no-brainer.”

His idea was met, instead, with a resounding no. Gold gave his idea the thumbs-down, describing her colleague’s proposed discussion as ‘a solution looking for a problem,” and citing the fact that “we don’t have that particular problem in Healdsburg.” Nor were the council’s other members in favor.

Over the past six years, the Healdsburg police had logged just 65 use-of-force incidents, with no shootings or deaths. The mayor was right in pointing out that the town didn’t have a problem with police violence.

She was wrong in surmising that there would be little interest in the conversation Naujokas was trying to kick-start. While it may not have a police problem, Healdsburg does have a racism problem – like most other cities and towns across America. Naujokas, a software engineer who’s lived in Healdsburg for 27 years, knew that. His hope, in calling for a formal discussion of police practices, was that “the community would show up,” and that the subject of racism in Healdsburg would be raised. “People would see that these issues impact a lot of our citizens, and that we need to keep the conversation going.”

It didn’t happen the way he’d planned, but Naujokas definitely got the conversation he wanted. And then some.

Detractors quickly pounced on Gold’s plea, in a June 3 Facebook post, that residents not attend a protest scheduled for following evening in Healdsburg’s downtown plaza – a demonstration that drew more than 600 people and was widely praised for its peaceful nature.

Gold gave further grist to her critics with her tart response to Elena Halvorsen, a local photographer who had emailed to express her displeasure with the mayor’s negative response to Naujokas. “I grew up in Healdsburg and am grateful that I have the opportunity to raise my children here,” wrote Halvorsen. “To say that racism is not a problem in Healdsburg is putting your white privilege on full display.”

In her defense, Gold never said systemic racism does not exist in Healdsburg. But that mattered little as the mayor came to represent something beyond what she had said.

After castigating the mayor for her blindness to “structural racism,” and for silencing “the experiences of thousands of your constituents,” Halvorsen challenged Gold to “examine your own white privilege and racial bias.”

The mayor’s reply was more succinct: “I really don’t know how to respond to your misplaced outrage and the hyperbolic tone of your letter. Perhaps after you have cooled down a bit we can arrange a civil phone conversation.”

That exchange was prominently featured in a petition, posted on Change.org, calling for Gold to resign. Just over one week and 1,800 signatures later, she did.

“I was snippy with her, and I regret that,” said Gold, in mid-July, of her response to Halvorsen. “It wasn’t appropriate.” Elected officials “need to have an endless supply of patience, and at that moment I was out of it.”

The ex-mayor is more combative than contrite, in retirement. Asked if she was sad, Gold replied, “I am sad – for representative democracy.”

Less than a week after the death of George Floyd, she and her fellow council-members were not fully aware of the breadth and depth and urgency of the Black Lives Matter movement.

“We’re not professional politicians,” she said, pointing out that council members essentially volunteer their time. “We get $135 a month. That’s our take-home, honey.”

When Naujokas started talking about a deep-dive discussion on use of force, “We were all just kind of like, ‘What? We all know this isn’t an issue. We’ve had no complaints. Our police chief is awesome.’” “Which is not the same as saying there’s no racism.”

Gold spent two weeks trying to explain to people that her words had been misconstrued. She was trying to reason with a group of people in no mood to be reasoned with.

“They were outraged, and looking for a focus for their outrage. Unfortunately, they focused on us,” she said, referring to the council. “And specifically, me. Which was very inappropriate.”

Five weeks after Gold left office, two other council members announced they would not seek reelection. Both Vice Mayor Shaun McCaffery, the council’s longest-serving member, and first-term council member Naujokas decided, like Gold, that they no longer wanted to serve. Both said they hoped to make room for people of color on the council so new voices could be heard.

Their departures leave three council seats open, ensuring that the political ferment initiated by Naujokas will continue into November and beyond.

While Gold expressed “relief ” to be out of the public eye, it rankles that many of her critics “didn’t know anything about me or my record. To them I was just an old white lady.”

Fluent in Spanish, she spent a year as an undergraduate in Mexico. Gold prided herself on her advocacy for Healdsburg’s Latinx community. When Leticia Romero, former executive director of Corazon Healdsburg, had a problem with tenants facing eviction, “she called me,” says Gold.

After her resignation, Gold got in her small RV and “literally drove into the sunset.” She returned a reporter’s call from a beach in Carmel, sounding as if she’d had quite enough of politics.

“I’m going to be apolitical for quite a while, I think.”

Taking note of the flak Gold was catching, her fellow council members performed an abrupt about-face. “I would just like to apologize for … not recognizing the urgency of the issue [Naujokas] brought before us,” Councilman David Hagele said at a subsequent meeting. “That was tone-deaf on my part, and, to our neighbors that felt marginalized or dismissed, I’m sorry.”

The council took Naujokas’ advice and invited Police Chief Kevin Burke to address it. Burke proposed hiring a bilingual, licensed social worker to fill one of the vacancies in his 18-officer department. That person would provide additional training to other officers in areas such as equity and unconscious bias.

The council loved it. Burke “saw the need for an honest, creative, out of the box proposal, and stepped up,” said Naujokas. “I was proud of our chief in that moment.”

The change kept coming. On her way out the door, Gold expressed the hope that her vacant seat might be filled by a person of color.

Her former colleagues obliged her, unanimously choosing Ozzy Jimenez, the 33-year-old CEO of Noble Folk Ice Cream & Pie Bar. A Piner High grad whose partner, Christian Sullberg, hails from Healdsburg, Jimenez enjoyed broad support in the community. Before convincing the city council to invite him aboard, however, he had to convince himself.

“It wasn’t my intention to civically engage this year,” he said. “But the ex-mayor left the door open for a person of color to fill the seat.”

Is there someone I could mentor? Jimenez recalled asking himself. Perhaps a community leader who needed a good sounding board?

Finally, he arrived at a conclusion: “I was like, I think it’s me. I think I have to do this.”

Jimenez, who is of Mexican descent, has long been acutely aware that nearly a third of Healdsburg “is not represented” in city or state government. Before joining the city council, he worked with non-profits, mainly Healdsburg Forever, to take on stubborn problems like food insecurity and the housing crisis. He’s looking forward, he said, to bringing his “nuanced knowledge” to the job.

“Ozzy stands strong for the most vulnerable in Northern Sonoma County,” noted Sen. McGuire in a congratulatory tweet. “He’s a civic-minded small business owner committed to doing good for his community.”

“I think this is a moment for celebration,” said Evelyn Mitchell, who replaced Gold as mayor, moments after the appointment of Jimenez. “It brings tears to my eyes.”

It was Mitchell who’d swiftly seconded Gold’s opinion, five weeks earlier, that a formal discussion of police use of force was unnecessary, a non-starter.

And it was Mitchell who’d cast the deciding vote allowing Jimenez to serve the remaining 2 ½ years of Gold’s term. The other option was to force him to run for reelection in November, when three other council seats will be up for grabs.

“We have gotten through what has proven to be an incredibly difficult time, and it really opened up our eyes to a lot of issues,” Mitchell went on. “I’m just sorry that it came this way. Nevertheless, we will move forward.”

We’ve seen the protests before, following the deaths of Freddie Gray in Baltimore (2015), Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, (2014), and, closer to home, Andy Lopez in Santa Rosa (2013), to name a few young men of color killed by police.

Fallout from the death of George Floyd has been far more widespread. It has led to a vast reckoning with racism that goes beyond police reform. Doug Hilberman, president of the Sonoma County Alliance, resigned in June after beginning a letter that was posted on the influential business group’s website with the words “ALL lives matter.” That phrase is viewed by the Black Lives Matter movement as offensive, a criticism that dismisses systemic racism that has devalued the lives of Black people.

Across the country, CEOs have resigned, statues have been torn down, and Confederate flags have been banned from NASCAR and U.S. military bases.

What’s different this time?

The author and historian Ibram X. Kendi draws a sharp distinction between being “non-racist” – a neutral, passive outlook – and being actively “antiracist.”

“One either allows racial inequities to persevere, as a racist, or confronts racial inequities, as an anti-racist,” he writes in his 2019 book “How To Be An Antiracist.”

“There is no in-between safe space of ‘not racist.’” One reason the Black Lives Matter movement has gained significant traction across the country since Floyd was killed is that Kendi’s proactive message, his warning against complacency, is resonating with a new generation of activists.

Skylaer Palacios, 25, is a graduate of Healdsburg High School who identifies as Black, Latina, and Native American (Arawak). She was Miss Sonoma County in 2014. While she’s pleased by the movement toward police reform in the wake of Floyd’s death, “it’s not enough.”

Banning chokeholds is a good start, she said.“But that’s treating a symptom, not the root cause.”

Nor is it enough, she added, for the Black Lives Matter protests to simply raise awareness of racial inequality. Reading an article about a protest does not equal “actually being willing to accept that you’re part of it.”

“This is everybody’s problem,” she said.

She remembers standing with her mother near the bleachers at Healdsburg High in 2009 for her brother’s commencement ceremony. They were looking for a place to sit. A woman near them scolded, “Speak English!” even though they had been speaking English.

“I can only imagine that she just saw our skin color and needed to find something to say to try and diminish us.”

Palacios has also expressed interest in running for a city council seat. While her focus would be primarily on affordable housing, she’s also advocating for “cultural awareness.” To her, that topic includes not just racial and ethnic awareness, but the shift she’s seen in Healdsburg from “the culture of the family and community to the culture of luxury and hospitality.”

Lupe Lopez also grew up in Healdsburg. She followed the Black Lives Matter movement and knew she wanted to contribute to it, “but didn’t know how.”

Then Leah Gold and the city council put their feet in their mouths, and a light went on for Lopez. She would give people of color a place to have their voices heard “in town that almost feels like it doesn’t validate them.”

She teamed up with Perez to make it happen. There they stood in the gazebo on June 11 as people filed through the exhibit, their expressions growing serious as they read the stories, and realized how far we have not come, how much work there is still to do.