Alegria De La Cruz and her family were walking home from a Santa Rosa park when they saw the Black Lives Matter demonstrators coming up Sonoma Avenue.

It was a balmy Saturday evening in June 2020. De La Cruz, the daughter and granddaughter of labor activists, felt right at home among the marchers. But her 13-year-old son, Ome, was less at ease. Picking up on tension between the police and protesters, he turned to his mother. “We gotta go,” he said. “This isn’t going to be safe.”

There were families and children among the protesters. “Do they look dangerous?” she asked him. They did not, Ome answered.

She told him about the strikes and protests her parents and grandparents had been a part of. “Imagine that’s your grandma,” she told her son, motioning to a couple. “That’s your grandpa. That little girl in the Snugli — that’s me.

“Those are our people.”

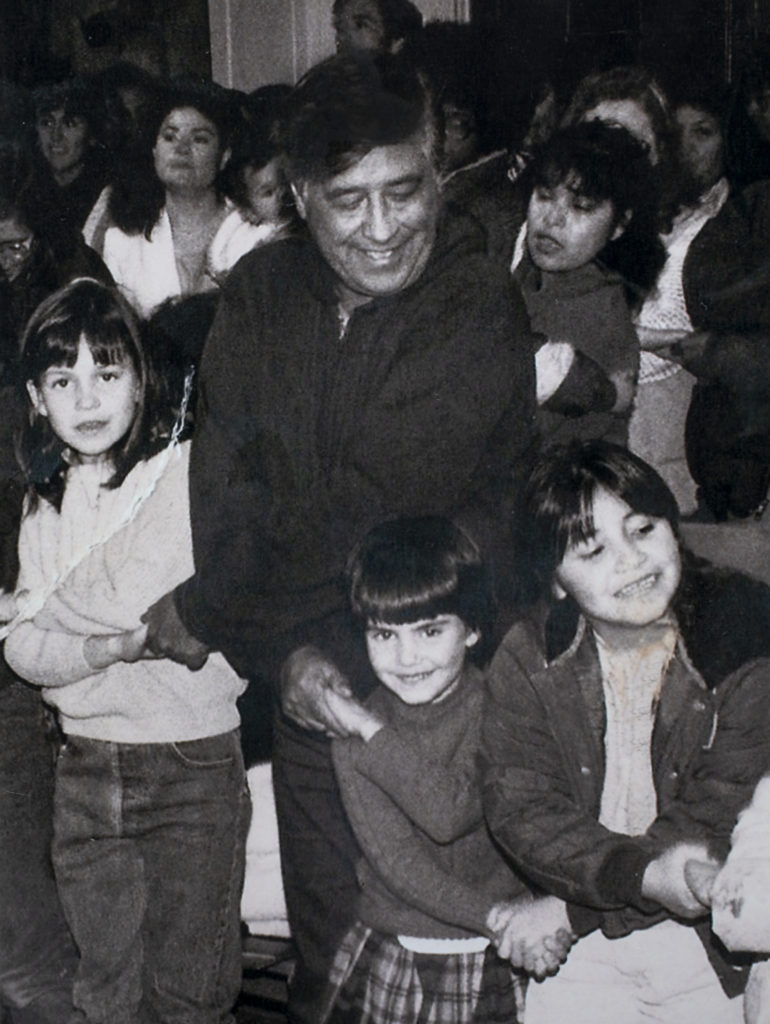

It was an apt cue for the newest generation in a line of family members who stepped from the farm fields of California a halfcentury ago and for decades have battled injustice and inequality, nearly always from outside the system. Now De La Cruz, a 44-year-old Sonoma County attorney who as a young girl held hands with Cesar Chavez at the height of his power, is waging her own campaign to right wrongs from within the

halls of local government.

She was chosen by the county Board of Supervisors last year to lead the new Office of Equity, established amid the large antiracism street protests last summer and in response to longstanding calls for action. Its mission is to root out racial inequality in county government — recommending new laws for the Board of Supervisors, crafting internal policy to build equity, and adjusting how services are delivered to prevent disparate racial outcomes.

It’s a crucible even for De La Cruz, a rising star in the County Counsel’s Office who earned acclaim in the chaos of the 2017 firestorm, when she was the lone conduit of public information for the region’s Spanish-speaking residents, translating emergency dispatches from the county and taking round-the-clock calls from those needing more immediate help.

One of her aims at this new job is to call out and fill those kinds of gaps. The county has since made strides addressing “language equity,” making sure it communicates to residents in English and Spanish. But De La Cruz said it will take more than just her small team—two people with no actual office space as of November

— to make meaningful change in the largest local government and public employer.

“There’s no way in hell we, alone, are going to be responsible for a culture shift in an organization of 4,000-plus people,” she said.

But change is coming, thanks to her allies in many of the county’s 26 departments — “champions” of equity, she calls them, “people who’ve been doing this work for a long time.”

Few have been doing it as long as De La Cruz.

Her story is, in a way, the tale of two grandmothers. Her father’s mother, Jesusita “Jessie” Lopez De La Cruz, the daughter of Mexican immigrants, worked in the fields of California’s San Joaquin and San Gabriel valleys with her parents starting at the age of 5. Jessie went on to become the first female organizer for the pioneering union, the United Farm Workers.

A confidant of Cesar Chavez, Jessie Lopez De La Cruz participated in strikes, served as a delegate to the Democratic National Convention, met with the Pope, and testified before the U.S. Senate, inviting the politicians to come to Fresno, where they might hear the needs of impoverished farmworkers firsthand.

De La Cruz recalls her maternal grandmother as another pivotal figure in her life, a “lovely” white woman from Long Beach who meant no harm when she told her, “Well, Alegria, if you’re going to be a short Mexican, at least stand up straight.”

As the daughter of organizers for the United Farm Workers, De La Cruz moved 15 times in the Central Valley by the age of 11. After graduating from high school in Boston, she went to Yale, where her extracurriculars included organizing local labor unions and leading the university’s chapter of MEChA, the Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán, which succeeded, among other things, in getting table grapes banned from Yale’s dining halls — part of a wider movement in universities at the time meant to honor a UFW boycott that began in the mid-1980s.

She also majored in history, played varsity lacrosse – she was a twotime high school All-American in the sport — and fit in comfortably with her fellow classmates. “When I went to Yale,” she recalls, “I knew which fork to use, because my grandmother drilled that into me when I was little. Not my brown grandma, my white grandma.

“I feel like I’ve always lived with a foot in two worlds,” she says — at ease on the fields of the Ivy League and in the crop rows of the Central Valley. The duality has made her keenly aware of white privilege, “of knowing what that looks like, and knowing what that feels like.”

It also helped prepare De La Cruz for the job now facing her. She took the reins of her new office at a uniquely charged moment: amid a global pandemic that has ravaged, in particular, the region’s communities of color. The county — and country — like few times before, has also been in the throes of a protest movement demanding greater accountability for police, more diverse leadership, and an end to systemic racism.

Her immediate priority: to focus on the disproportionate impact of Covid-19 on the region’s Latino and Indigenous communities. At its peak, the county’s Latino residents made up nearly 80 percent of area coronavirus cases – including 98% of infections among children 17 and under. Latinos comprise 27% of the county population.

The virus “feeds on, and exacerbates, inequity,” says Supervisor James Gore, who helped spearhead the establishment of the equity office. So glaring was the need for such an agency that the supervisors

earmarked $800,000 to quickly get it up and running, despite a projected $50 million budget deficit.

The supervisors plucked De La Cruz from the County Counsel’s Office, where she’d served since 2017 as chief deputy county counsel. After earning her law degree at UC Berkeley in 2003, De La Cruz leapt into work geared toward improving the lives of underserved, invisible Californians, crisscrossing the state to litigate cases ranging from fair pay to housing, civil rights to environmental justice.

“A complete rock star,” is how Gore describes her. Supervisor Lynda Hopkins calls De La Cruz “a powerful leader,” and, in a less guarded moment, “a badass.”

The two got to know each other during the North Bay wildfires of 2017, when “Alegria and (deputy public defender) Bernice Espinoza “were the only people in county government trying to help Spanish speakers through the disaster,” says Hopkins.

De La Cruz recalls the awe she felt, working in the Emergency Operations Center with people “from all walks of the county in one room, solving critical problems in real time.”

She also remembers thinking: “I don’t hear Spanish. Why don’t I hear Spanish?”

She raised that concern with officials. Their response: “Can you help with that?”

She could, and did.

“For a while,” says Hopkins, “anyone calling 211, seeking information in Spanish was literally routed to Alegria’s cell phone.”

De La Cruz filled another yawning gap this past spring by helping to form a working group that directed the county’s resources as Covid-19 took its disproportionate toll on the region’s minorities. The resulting outreach has sought to ease access to medical care and quarantine space for affected residents and help with lost wages for those convalescing or tending to a loved one.

“The existence of this racialized spike tells us that we have failed,” says De La Cruz. The spike exists for a variety of reasons, she added, “because these folks don’t have a medical home, because they’re not connected to county messaging, or access to masks, or because they work for employers who maybe don’t know these things either.”

Long before the Office of Equity was founded, De La Cruz, Espinoza, and countless others were working to root out racial inequities and unjust policies in county government. But much of that work was extra — “on top of their normal jobs,” says Gore, resulting in frustration, demoralization and exhaustion.

Gore recalls being challenged at an “equity summit” last spring. Herman J. Hernandez, founder of the Latino leadership group Los Cien, told him that all the talk of diversity, inclusion and equity, without more meaningful action from the county, was “starting to taste like burnt coffee.”

By forming the equity office — one modeled off similar entities in Marin,

San Francisco and Santa Clara counties — and putting De La Cruz in charge, Sonoma County was “walking the walk,” Gore said.

De La Cruz has been on that path most of her life.

Eleven years before Alegria was born, her grandmother, Jessie Lopez De La Cruz, was making coffee for the men.

It was December 1965, and Cesar Chavez was going from house to house in Parlier, 20 miles southeast of Fresno, talking to laborers about joining his movement.

After answering the door, Jessie’s husband, Arnold, invited Chavez in, then sent his wife to the kitchen.

Jessie stood at the door, eavesdropping. She heard Chavez ask Arnold, “Does your wife work in the fields?”

“When grandpa told him yes, he said ‘She should probably join us for this conversation.’” It’s been a source of mirth – alegría – in the family ever since: When Arnold opened the door, his wife nearly fell into the living room. “She always said, ‘I was ready for my life to change,’” recalls her granddaughter.

Jessie was one of the first women to go into the fields and recruit for the UFW, a job at which she excelled. In 1968, she and Arnold ran the UFW’s first hiring hall out of their garage. After her death — on Labor Day, 2013, at the age of 93 — she was recognized by then-UFW president Arturo Rodriguez as “one of the best organizers the UFW ever had.”

De La Cruz’s mother, Jan Peterson, was a fearless organizer who once won 33 straight union elections, mostly in the tomato fields of the Stockton and Patterson area in 1975, while she was pregnant with Alegria.

“’She spoke Spanish like a farm worker,’” De La Cruz recounted Chavez telling her once about her mother, a tribute included in Peterson’s 2018 obituary. ‘She would stand up on an empty box in the middle of a field to be heard and all these workers would follow her out on strike. I never saw anything like it. I want you to know that is your mom — and what a really great organizer she is.’”

So committed to the cause was Alegria’s father, Roberto De La Cruz, that he returned on leave from his Navy tour of duty in Vietnam to join Chavez and other striking farmworkers in 1966 for part of their historic, 340-mile march from Delano to Sacramento.

“My dad talks about what it means to never have your own land,” says De La Cruz, “to always be working someone else’s, and to know that land better than its owner, because you’ve worked it so hard, yet to be treated with such disrespect, so little value.”

She was 11 when the family moved to Boston. The real estate agent helping them find a home looked at her white mother and Mexican-American father, and suggested that he not join them when it came time to look for homes.

As “a little Chicana” from California, De La Cruz was “a fish out of water” at her public school in Milton, Mass. But she hit her stride, as a student and athlete, at Thayer Academy. When financial aid officers at the private school south of Boston reviewed her application for assistance, they ‘wondered if there was a zero missing from our tax docs, because my parents made so little from the UFW,’ she recalls with a smile. ‘I was a scholarship kid all the way.’

De La Cruz relished “the release” that lacrosse gave her at Thayer and noticed that those playing fields “felt more level than the rest of my life.”

De La Cruz emerged one day from the counselor’s office at Thayer with

a list of colleges to which she intended to apply. On it were lacrosse powerhouses like Maryland and Delaware. “I was fired up,” she recalls.

Reading that list, her coach — a short Italian woman — became angry, then marched with De La Cruz back to the counselor’s office. “I don’t know what you’re thinking,” her coach told the counselor, “but this kid’s frikkin’ smaht,” recalls De La Cruz, breaking out her Boston accent.

“I want some Ivies on her list.”

The counselor obliged. De La Cruz was scouted by Dartmouth, Princeton, Harvard, and Yale, where she majored in history, with a focus on the labor movement. Her final project was an oral history of her grandmother.

The lacrosse team was another proving ground. After two years “riding the bench,” she was named most improved player in 1997, and got plenty of playing time in her final two years. But what she remembers most vividly — and painfully — about her time with the squad was something that happened off the field.

In the spring of her junior year, a group of first-year players dressed up as the Ten Little Indians as part of an initiation ritual. Furious and hurt, De La Cruz “marched them home and scrubbed off their faces,” she recalls, letting them know how disrespectful she found their costumes. “This is a Native American sport,” she recalled telling teammates, her voice still quavering with outrage decades later. “You can’t do this to people.”

After returning to California, she enrolled at the UC Berkeley School of Law a few years after the passage of Proposition 209, which banned affirmative action in California, resulting in, as she remembers, “the whitest classes” at the university since before the Civil Rights Act. “We stood out,” she says of her fellow students of color. With allies in the law school’s Coalition for Diversity, she wrote amicus briefs and organized with other groups to fight Prop. 209–like efforts in other states.

Her first job out of law school was back in the San Joaquin Valley, with the California Rural Legal Assistance, fighting environmental injustice, including water pollution and pesticide exposure that disproportionately affect low-income farmworkers in the region. Those six years were also formative: She came to see, more clearly than ever, huge gaps in systems that were supposed to be airtight. “My clients were the ones who fell through the cracks,” she says. Because they were poor and dark-skinned and often spoke little English, “they were invisible.”

“The thing I remember about her,” said Martha Guzman, who worked with De La Cruz at the CRLA, “is that she’d go anywhere and everywhere there was a case.” Guzman, who is now an appointed member of the state’s Public Utilities Commission, remembers in particular a case in Del Norte County involving a large group of Indigenous Mexican farmworkers who were being housed at the fairgrounds, and given inadequate food.

De La Cruz was on it, working cases from one end of the state to the other.

“Del Norte, the Imperial Valley — she was always willing to get up and go,” Guzman said.

It was Guzman in 2011 who suggested to De La Cruz — by that time the legal director of the Center on Race, Poverty & the Environment in San Francisco — that she might do even more good working inside government.

“What are you talking about?” she replied. “I sue the government.”

But she changed her thinking, and, after an interview with then-Gov. Jerry Brown, joined the state’s Agricultural Labor Relations Board as a supervising attorney, based out of Salinas, the urban engine of California’s other famed agricultural valley. The work was rewarding, but grueling — and stressful.

At her direction, that board was filing more litigation than it had “in 30 years,” says De La Cruz. “So there was a lot of controversy, a lot of personal attacks, a lot of big white trucks sitting outside my house at all hours of the night.

“My office got broken into, my car got broken into. I’m like, ‘It’s 2012. How am I living the movie “Silkwood” practicing labor law in Salinas?’ But it was still that frightening for some people to think about farmworkers having their rights respected.”

After three years in Salinas, De La Cruz and her husband, the artist Martin Zuniga, looked north. During their time in the Central Valley, Ome had been diagnosed with asthma. She had an aunt in Cotati. In 2015, the family of four relocated to Santa Rosa, opting for a new part of California with cleaner air.

The timing of that move exposed the family and De La Cruz to the brunt of three historic fire seasons in Sonoma County, including the 2017 infernos that earned her a spotlight for service to Spanish-speaking residents.

Fast-forward to the wildfires that ravaged the West Coast this past summer and fall, and the threads of De La Cruz’s career have come full circle: environmental pollution layered on the deep deprivation imposed by the pandemic.

“I was like, damn, we came here so we could breathe, and now we’ve got air filters in the house, and nobody can go outside,” says De La Cruz, with a laugh.

Upon joining the county counsel’s office, she found a mentor in Bruce Goldstein, who has “a justice warrior’s heart,” says De La Cruz. Goldstein retired in September 2020, after running that department for a decade.

Over a beer in November, he and De La Cruz had a laugh recalling her disastrous job interview in 2015. Inspired by what she knew of the Santa Clara county counsel, which went after bad actors like polluters and opiate manufacturers, De La Cruz spoke passionately about how she could do the same thing in Sonoma County.

Around the table, people looked down at their hands. Sonoma County wasn’t interested in that kind of aggressive, plaintiff-side practice. “And I’m sitting there thinking, ‘Ooooh, this is not going well,’” she recalls. “I remember walking out and saying to myself, ‘OK — didn’t get that job.’” She was wrong about that. Goldstein and Sheryl Bratton, now the county’s administrative officer, reached out to De La Cruz, asking “What would make you happy here?”

She started off working on land-use policy, advising Permit Sonoma, the county’s planning agency, and the Community Development Commission, which focuses on, among other things, affordable housing and homelessness. De La Cruz also helped create the Secure Families Collaborative, a legal aid initiative aimed at helping immigrant families following the election of President Donald Trump.

To further knit herself into the community, she sought and secured appointment to an open board seat with Santa Rosa City Schools, where she has served as a trustee since 2019. De La Cruz also serves on the board of Los Cien, the Latino leadership organization, which had long pleaded with the county to more proactively address its structural biases.

As she stood in mid-June on Sonoma Avenue with her son, watching Black Lives Matter protesters file past, De La Cruz recalls Ome asking: “Why do the police have so much armor on?”

She smiled, and replied, “Those are the questions I want you to be asking.”

In her new role, De La Cruz faces plenty of key questions herself, including from the Board of Supervisors and a public pushing for change at a moment of “national awakening,” says Chair Susan Gorin. Foremost among them: How will we know the Office of Equity is succeeding?

In the long term, De La Cruz replies, it will it result in changed outcomes — in life expectancy, health, wealth, educational attainment.

In an equitable society, she points out, those outcomes won’t vary between racial and ethnic groups. Latinos in Sonoma County, for example, will be no more likely than other groups to contract the coronavirus.

It’s a daunting assignment, but De La Cruz’s work begins with the task of helping her colleagues in the county understand that the roots of inequity are located “in government inaction,” she says.

“Government created redlining, fencelining, and other programs that exclude minorities,” she notes. “Now government can change those outcomes.” But first it has to acknowledge its role in the problem. “You have to see the gaps you created,” she says.

In that light, the work ahead of her is revealed as both a continuation of the campaigns her loved ones led for years and a manifestation of some of the very change they sought. Because she is doing it from the inside.

“I think about where I come from every day,” she says. “I do my best to honor that history.”