Driving in an ATV through rocky vineyards partway up the side of Moon Mountain outside Sonoma, Phil Coturri stops for a moment to look at a steep hillside row of Cabernet Franc. “The fruit that comes off the top is a little different than the fruit that comes off the bottom,” he says. “My job is to create uniformity out of this chaotic environment. I operate on chaos because I live in chaos.”

It might be the third or fourth time he’s said “chaos” in the last couple of hours. It’s a family obsession. “We joke all the time that that’s just the Italian in us,” says his son Sam Coturri, who runs the family’s Winery Sixteen 600. “We always want to figure out the hardest possible way to do something.”

It was already difficult enough being a pioneer organic grape grower in the late 1970s, when nearly everyone farmed with chemicals. But Coturri took it a step further, carving out a niche cultivating rugged, difficult-to-harvest biodynamic vineyards. They make up the majority of the 700 acres he farms with Enterprise Vineyards today, some running as steep as 40% grade.

“It’s like mountain-grown coffee,” he says. “You want to grow a healthy, robust vine under the worst possible conditions. That’s where you get the intense flavors. That’s how you create terroir. Terroir is soils, slopes, aspects—and the attitude of the grower.”

A few minutes later, Coturri drives to the top of another hill, where you can see all the way to San Francisco on a clear day, only to let his foot off the brake and barrel down a sloped row, the ATV bobbing back and forth on volcanic rocks, as misters spray him on the way down. It could be a Disney ride.

“People pay a lot of money to ride through the vineyards with me,” he says, half-joking.

When he laughs, his wild eyebrows flicker. A lifelong Deadhead, with long hair tied loose in a ponytail hanging over a tie-dye shirt, topped off with a straw Panama hat, he’s a magical bramble of a man. If there were a Hobbit character who tended vineyards in the Shire, he would probably look a lot like Coturri.

If you throw out a year, he can tell you what the harvest conditions were like that season. Whether it’s 1998, which was “a cool year, not a big yield, but incredible wines if you can find them.” Or 2009, when “the Oregon Express brought 9 inches of rain on the 9th of October.” Or 2010, when crews thinned the canopy leaves too early and the sun scorched the grapes.

The weekend before the ad hoc Disney ATV ride, he flew to upstate New York to see Dead and Company on their farewell tour. His best friend in the band, drummer Bill Kreutzmann, is sitting this one out. Since the late ’70s, when he befriended sound engineer Dan Healy, Coturri has seen the Dead dozens of times, watching every show from the soundboard.

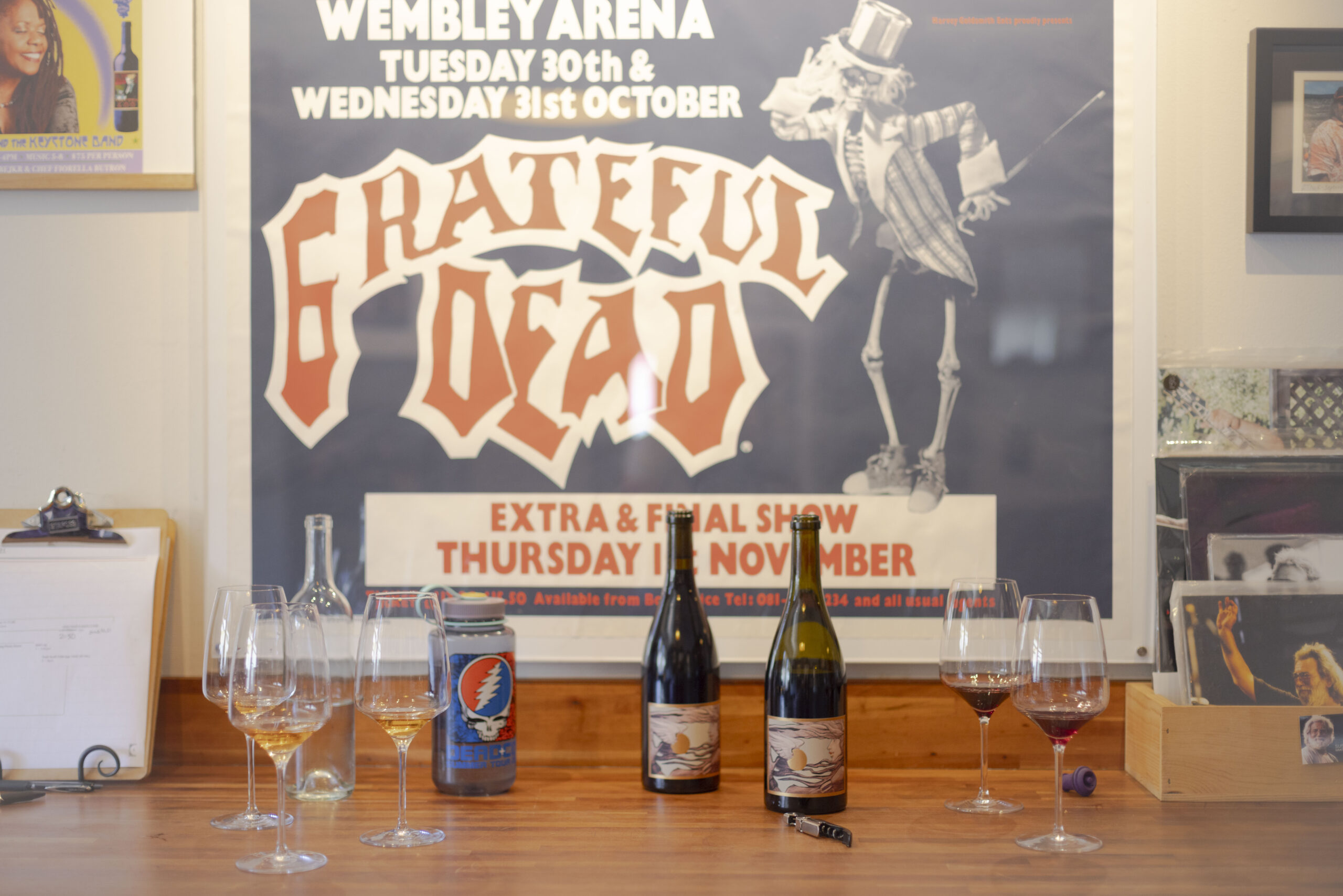

His Winery Sixteen 600 tasting room, a few blocks off the square in downtown Sonoma, is decked out with so much Grateful Dead memorabilia, from German subway concert posters to psychedelic art by Stanley Mouse, who designs his wine labels, that it feels equal parts museum and winery. Ask him about his favorite mementos and he undoes his belt to show off a buckle with a Dead skull designed by sound engineer Owsley “Bear” Stanley. Only $35 when he picked it up at a Greek Theatre show decades ago, it’s worth at least $5,000 today.

If music is the journey that’s taken Coturri halfway around the world on an endless caravan of Dead shows, then wine is what’s in his blood. His grandfathers were both barrel coopers. His grandmother emigrated from Switzerland to work at the Italian Swiss Colony in Asti. After she won a landmark paternity suit (one that, according to family lore, involved the colony owner’s son), her settlement included an allotment of Asti grapes every harvest. It’s how the family made wine in the early days.

Phil Coturri grew up in “the Italian ghetto” of San Francisco’s Visitacion Valley, where his father, Harry “Red” Coturri, ran a janitorial supply business and his mother, Fermine Coturri, was a schoolteacher. When he was 8, his parents bought a country house on Enterprise Road on Sonoma Mountain in Glen Ellen, where they planted 2 acres of Zinfandel. At age 11, he learned to make wine with his father and brother, Tony.

A well-read, occasionally mischievous kid, Coturri once nearly burned down his grandmother’s house. When he was 14, his mother found three ounces of marijuana in his pockets. To keep him out of trouble, just as he was getting into the San Francisco music scene and Beat poetry, his parents took him up to the country on weekends and summers.

A hippie during the back-to-the-land movement, he fell in love with working in the vineyards. In 1979, when neighbor Myron Freiberg challenged him to grow grapes organically in his 12-acre Dos Limones vineyard, Coturri jumped at the chance. He was already organically farming vegetables and marijuana. If it’s true, as cannabis guru Ed Rosenthal once joked, that “smoking marijuana is not addictive, but growing it is,” then Coturri was hooked from the get-go.

Putting his green thumb to work in the vineyard, he befriended a retired colonel who lived nearby and taught him how to drive a tractor as a teenager, turning him on to Organic Gardening magazine. Old-world grape farmer Joe Miami, who tended Louis Martini’s fabled Monte Rosso mountain vineyard, showed him how to plant and prune vines and how to cultivate the soil. Farmer Bob Cannard, who would later grow vegetables for Alice Waters at Chez Panisse, taught him about cover crops.

But scaling from a 1-acre garden and guerrilla pot grows to a large organic vineyard took a huge leap of faith. “Back then, vineyards were as manicured as a pool table,” he remembers. Most wineries wanted to kill every weed before it grew. As a teenager, Coturri had been paid to spray paraquat in vineyards, around the same time the Mexican government was spraying the toxic herbicide on marijuana farms south of the border. It didn’t feel (or smell) like the right thing to do, he remembers. Now, he was in charge. That’s when he began formulating his year-round organic growing philosophy: “I like to say, from April 1 to November 1, I grow grapes. And then from November 1 to April 1, I grow soils. I grow cover crops to enhance the environment in which my grapes are grown.”

In return, the vineyards have been kind to him. It’s where he met his wife, Arden Kremer. “I needed a job, so I called my girlfriend and she said, ‘Call this guy Phil Coturri, he’s running a grape-picking crew,’” she remembers, like it was yesterday. As she tells the story, Kremer is standing in the middle of their living room, in the family house on Norrbom Road where they’ve lived for nearly 40 years, perched on a shady hilltop overlooking Agua Caliente Canyon north of Sonoma.

The pay back then was only $1 a box. “On a good day, you’d make like $30,” she says. “That was really good back then. A loaf of bread was 79 cents in 1977.”

After a long day picking grapes at Rossi Ranch in Kenwood, everybody went back to Coturri’s place. “I walked into this house that was lined with Grateful Dead posters and rock ’n ’roll stuff from the Fillmore,” Kremer remembers. “And I went, ‘Oh yeah, this is the guy for me.’” Decades later, their sons, Sam and Max, work in the family business. Watching their father work long hours, often at the mercy of Mother Nature, each found a calling. “Sam loves talking to people, and Max loves riding on a tractor,” their father explains. Max now oversees the construction of new vineyards for his vineyard management company. And Sam is the winery’s technical director, focusing on Rhone varieties like Syrah, Grenache, and Mourvèdre, along with Zinfandel and Cabernet Sauvignon.

By 1980, a year after Coturri started Enterprise Vineyards, his organic grapes were thriving. Just like local organic tomatoes or organic peaches, word spread on a grassroots level and his clientele began to grow. “The trick back then was to convince clients the vineyards were going to look a little weedy like me, and that was OK,” he says. “The vines would be tended for, but it wouldn’t be a sterile environment.”

It also took a leap of faith for winery owners to say, “Here’s $50,000 an acre to go plant a vineyard,” he says. Today it’s more like $120,000 to $150,000 an acre.

“It takes some cojones to make that transition to organic,” says Will Bucklin, winemaker at Bucklin Old Hill Ranch in Glen Ellen, who has worked with Coturri for nearly a quarter century. “Having Phil on board to do that gives you the confidence.”

And it’s not just Coturri. His loyal crew has the same set of skills. Many of them stick with his company their entire career. “Two years ago, I took a photograph of the crew during harvest, and almost everybody in that picture had been working with us for 20 years,” Bucklin says.

As an organic farmer, Coturri typically charges around 15-25% more than conventional farmers. “The bottom line is you can’t cut corners,” he says. “You have to have the best fruit to make the best wines.” That means he cares just as much about the environment that surrounds the vineyards—the woods, the creeks and the salmon. An English major at Sonoma State University, he has never forgotten poet Gary Snyder’s edict that “To be a poet, you have to know all the names of all the plants and all the animals of the watershed that you live in.’” Poet or viticulturist, he took it to heart—and took it one step further, by protecting that watershed. “It doesn’t mean anything when you call something ‘sustainable’ and then you’re using something that poisons the groundwater,” he says.

His big leap came in 1983, a few years before he bought his property off Norrbom Road for $140,000. He became good friends with his soon-to-be neighbor, screenwriter Robert Kamen, who dreamed of making world-class Cabernet Sauvignon and hired Coturri to plant his grapes. This was his chance to finally design and build a large-scale, 50-acre organic vineyard from scratch, designing the network of vineyard blocks, trellising systems, access roads, hedgerows and other flora and fauna, and irrigation (that irrigation also pumps in compost teas infused with fish oil and worm castings). Actor Danny Glover also hired him to farm his nearby vineyard. (Metallica guitarist Kirk Hammett also lives around the corner, but doesn’t grow grapes.)

Living and breathing the volcanic terroir, Coturri would be instrumental in the designation of the Moon Mountain District AVA in 2013. But in the ’80s and ’90s, it was just a dream.

“It was like the Wild West back then,” remembers winemaker Jeff Baker, who made award-winning Mayacamas Vineyards and Carmenet wines from Coturri’s grapes. One story has them dynamiting hillsides to build vineyards. Another has Coturri ducking for cover as Huey helicopters flew over, scouring the land for pot gardens in the ongoing war on drugs.

There’s the day in 1989, when the Grateful Dead crew set up equipment in Coturri’s barn off Norrbom Road to test out the band’s latest “Wall of Sound” technology and an oak tree split in half and crashed to the ground. To this day, no one knows if it was felled by sound waves or an act of nature.

Today, Coturri farms biodynamic vineyards from western Solano County to the top of Sonoma Mountain, employing more than 150 workers. He tends grapes at Oakville Ranch, Repris, Laurel Glen, and Mayacamas Vineyards, among many others. For most of his clients, money is no object. They include former Pixar czar John Lasseter; the family of Jim Simons, the billionaire hedge fund manager; Mary Miner, widow of Oracle co-founder Bob Miner; comedian Tommy Smothers; and musician Boz Scaggs. A few clients (think AI pioneers) he can’t even name due to nondisclosure agreements.

“Rich people like to have stories to talk about, and Phil definitely gives you something to talk about,” says Baker. “By Napa standards, it’s not that expensive. In Sonoma, it’s still expensive farming. But there’s a big difference between getting $10 a bottle for your wine and getting $300 a bottle.”

Rattling off examples, Coturri mentions Lasseter Family Wines, which sells a $160 bottle. Kamen Estate Wines has $200 bottles, as does Mayacamas Vineyards. Repris released a $250 bottle. At Winery Sixteen 600, he makes a $150 bottle.

Winemaker Richard Arrowood once described him as “a winemaker’s grower,” which Coturri took to mean that he cares more about the end product than he does making a profit selling grapes.

Over the years, Coturri has famously “fired” clients who try to talk him into cutting corners and lowering organic standards. “With Phil it’s pretty much ‘my way or the highway’ in terms of farming,” Baker says. “He doesn’t need new clients. He needs clients that will let him farm for the highest quality. If they just want quantity or something like that, he tells them to find someone else.”

“Everything I do is a pain in the ass. I make my life more difficult. It would be much easier to go spray Roundup and use steroid inhibitors and spray for mildew. But to do it organically, it’s not easy. It’s all about blood, sweat, and tears.”

With one foot in the past and the other in the future, Coturri is always looking for ways to incorporate new technology in his vineyards. It’s part of his attraction to philosopher Buckminster Fuller’s theories on applied technology. Enterprise Vineyards recently bought an electric Monarch tractor and is prepping it for a trial run in the more than 100-year-old Barricia Vineyards. With a drill screaming in the background, the company’s director of technology, Matt Simpson, flips open a laptop on a work bench and together they navigate heat-resolution maps and soil-sensor data to pinpoint vines that are stressed and might need water.

“We’re looking to substantiate our intuition and take the guessing out of it,” Coturri says. “We don’t want to over-water, and we don’t want to under-water.”

Out front, a sales rep is demonstrating a new automatic tool that should speed the labor-intensive job of hand-tying canes in the vineyard after pruning. Coturri wants to hear what his vineyard workers think about the tool before he spends $1,500 apiece on nearly a dozen of them.

Teaming up with Kiatra Vineyards in Napa, he’s also working on a 4-acre test plot to create a high-tech, computer-monitored vineyard that goes beyond organic to produce zero emissions on the farm. He’s hoping it will be the wave of the future for Sonoma and Napa vineyards: “Not only are our neighbors watching us, but also our neighbors from afar, our friendly competition with the European market. They’re watching and learning, too.”

With harvest looming, Coturri hops in the ATV again and drives down a few more rows, stopping to pull tiny berries off the young green clusters, splitting them open with his thumb to see how many seeds are inside. It’s an early hands-on indicator of what the season might bring. Walking down a row, he stops to pull up his baggy shorts and show the scars on his knees where he’s had replacement surgeries. “I’m gonna do this until I can’t walk anymore,” he says, attributing the wear and tear to the rocky vineyards he likes to farm.

At 70, succession weighs heavily on his mind. It’s not far below the surface when he wakes each day around 4:30 a.m. and does his stretches. Every vineyard he sees from his window, he farms. Angular and steep, they look like wallpaper from a distance.

He hasn’t watched the popular HBO series “Succession,” about a media mogul grappling with how to hand over the reins to his company. But he knows what it’s about.

“Mine is a hippie succession,” he says with a laugh. In March 2022, he thought he had found his successor. He lured Mayacamas Olds from Gloria Ferrer and named her as COO. She was practically family. His wife used to babysit Olds, and later Olds babysat Sam and Max Coturri.

But she lasted less than a year. “I’m sad it didn’t work out,” Coturri says. The reasons can be debated. Maybe she wanted to make the grassroots company more structured and corporate. Maybe he wanted to keep the hippie ethos that built it from the ground up. But they mutually parted ways this past January. Let’s just say that the annual tie-dye shirts that staff don every harvest will continue to be a company tradition.

Nearly once a month for the past three years, the family has met with a succession specialist to discuss what Sam Coturri calls “the perpetual five-year plan.” By now, it’s become apparent it will likely take a team, instead of a single person, to succeed Phil Coturri. That’s what happens when you try to follow in the footsteps of the godfather of organic viticulture in Sonoma County. After he turned 70, he promised his wife he would work fewer hours. But as he makes the rounds from the office to the vineyards this morning, he seems to have a question for nearly every employee he runs across. It’s obvious he’s still on top of all aspects of the business.

A few days later, as Coturri chats about the Dead and Company show he saw the night before, it all becomes crystal clear. Just like his musical heroes, who don’t really know how to call it quits—even if they cut back the frequency of shows, even after announcing farewell tours on top of farewell tours—Coturri doesn’t know how to walk away either.

“How do you quit something that you love, that has been a part of your life for 50 or 60 years?” he says. “You figure out a way to pass it on. Succession is a bumpy road, and to make everything work out in harmony, it takes a lot of practice. There’s a lot of repetition in quitting. Do you quit or just slow down?”

Looking back, it’s all been one continuous thread: grapes, grass, and the Grateful Dead. And it’ll never really end, this long, strange trip up and down mountains, through canyons and vineyards, kickstarted by a burly, long-haired hippie on a tractor in the ‘70s. Even when he can no longer walk, his organic spirit will live on in the cover crops and the hawk boxes and the compost teas—and in the new round of Enterprise Vineyards tie-dye T-shirts each harvest.

Later, scratching his gray beard for thought, Coturri paraphrases Gary Snyder’s “Hay for the Horses” poem and says, “I used to say about working in the vineyards, ‘I’d sure hate to do that the rest of my life.’ But dammit, that’s just what I’ve gone and done.’”

Phil Coturri’s Lifelong Top 10 Wines

LOUIS MARTINI MONTE ROSSO BARBERA, 1958: “An a-ha moment in mountain viticulture.”

DOMAINE DE LA BARROCHE PURE, 2013: “The pinnacle I look to when tasting and making Grenache.”

HANZELL PINOT NOIR, 1956-1996: “Tasting legends with the legend, Bob Sessions.”

MAYACAMAS CABERNET SAUVIGNON, 1962-2009: “Just after Bob Travers sold the property to new owners. The past and the future of a historic site.”

CARMENET CABERNET FRANC, 1983-1993: “With legendary winemaker Jeff Baker, a showcase in terroir from a notoriously finicky variety.”

COTURRI WINERY P. COTURRI ESTATE ZINFANDEL, 1993: “The Gourmet Magazine 1995 Wine of the Year, with label art by my son Max, who was 6 at the time.”

JESSANDRA VITTORIA KAMEN VINEYARD SANGIOVESE, 1997: “A dark horse in the lineup, but a wine that at its peak was impossible to put down.”

KAMEN ESTATE ‘KASHMIR,’ 2005: “A best-barrel compilation of Cabernet Sauvignon from winemaker Mark Herold.”

Á DEUX TÊTES ROSSI RANCH AND OAKVILLE RANCH, 2018: “The first release of our collaboration with the late, great Philippe Cambie, after years of friendship and mutual admiration.”

WINERY SIXTEEN 600 DOS LIMONES SYRAH, 2007: “One of the first wines we made under the Sixteen 600 label. Proof of concept for our brand of terroir-driven, farmer-styled wines.”