It was Mother’s Day, and as she has so many times in the past, Maria Dominguez had brought her family to the Sonoma Coast, where her problems always seem smaller when cast against the vastness of the ocean.

Dominguez, a divorced mother facing eviction from her Santa Rosa home because her landlord wants to sell, gathered her three teenage kids and made the 45-minute drive to North Salmon Creek Beach, where her family has free access to a wide swath of sand edging the Pacific just north of Bodega Bay.

The popular beach is part of Sonoma Coast State Park, which has encompassed 17 miles of this lightly developed coastline for more than 80 years.

An hour after Dominguez parked the family’s Ford Expedition on an overcast morning, dozens of other families had filled the free lot, one of several in the state park that beckons Californians and visitors from around the world to a public shoreline.

It was here, 21 years ago, that Dominguez, then just a 17-year-old girl recently arrived from Mexico, first saw the ocean.

“Don’t look,” a boy who’d ridden out to the coast with her said as they approached the cliff overlooking the beach. Moments later, she opened her eyes.

“Ay, Dios mío,” she said. Oh, my God.

Generations of county residents and visitors have been similarly awestruck and enthralled during visits to the Sonoma Coast and 10 other state parks, nature reserves and historic sites within the county.

Few outdoor experiences can compare with standing on Gunsight Rock in Sugarloaf Ridge State Park near Kenwood, strolling amid giant redwoods in Armstrong Woods in Guerneville or spotting whales off Bodega Head. Fans of the author Jack London flock to the state park near Glen Ellen bearing his name, while in the city of Sonoma, mission barracks and the home of Gen. Mariano Vallejo give visitors a glimpse of life in California before it became a state.

Now, to sustain California’s parks into the 21st century, state officials say the system needs an overhaul.

The transformation, as outlined by a panel appointed by Gov. Jerry Brown, is meant to move past a management scandal that engulfed the parks system in 2012 and to extend the promise of places that serve as playground, refuge, classroom and museum for up to 75 million visitors a year.

That future hinges in part on a plan to improve fee collection statewide. But the Sonoma Coast is the only place in California where the state is seeking new fees, advancing an unpopular plan to impose day-use charges of up to $8 at eight coastal sites that have always been free.

The infusion of money would help parks offer more services, protect more land and open new sites for future generations to enjoy, explained John Laird, California’s secretary for natural resources overseeing state parks.

Laird was an assemblyman during the recession, when a budget gap decades in the making for the parks department became a crisis. Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger’s administration floated a plan to close dozens of parks.

To stave off that scenario, Laird backed a proposal in the Legislature that would have pumped millions into the parks system through an increase in vehicle license fees. It failed to gain support, and in 2010 California voters rejected a similar measure at the ballot box.

Laird took the defeats personally. Born in Santa Rosa, he has fond memories of time spent at his grandparents’ ranch on Gravenstein Highway and trips to the Sonoma Coast with his dad, where the pair tossed tennis balls into the ocean and let the waves carry them back.

“That’s a precious resource that we have to turn over to future generations, and really, is the reason I wanted a long-term fix,” Laird said. “The voters didn’t agree, and we’re stuck in this position. We’re trying to figure out, within the context of the budget, how to do things more efficiently and how to get more money from the Legislature when we can.”

The latest, most significant bids to secure more money for parks include proposed taxes on marijuana — medical and recreational — and a bond measure that could go to voters in November. Each would generate tens of millions of dollars annually.

The state’s fee expansion, meanwhile, has been met by stiff local resistance reminiscent of the “Free Our Beaches” protests 25 years ago, when the state implemented — and then quickly rescinded —similar fees at several Sonoma Coast spots.

Fee opponents, including coastal access advocates and county officials, say the proposal threatens a history of unconstrained public access to the state’s coast, a guaranteed right under the state’s constitution and 1976 Coastal Act. That was the legacy of a pioneering movement launched in Sonoma County by environmental activists more than 50 years ago.

Richard Charter is a Bodega Bay resident who over four decades has fought to protect the North Coast from offshore drilling and preserve public access. Charter questions why visitors would pay extra at sites that offer few amenities beyond a parking lot and portable restrooms.

“People are used to paying for campsites or museums,” said Charter, a senior fellow with the Washington D.C.-based Ocean Foundation. “It’s when the state, because of a certain amount of malfeasance in Sacramento, sees a gravel parking lot with an overflowing Porta-Potty as something they can start charging for, I think that raises the main questions now.”

But the free park sites make Sonoma County an outlier compared with other parts of the state, where entrance fees are routinely charged, Laird said.

“If the people of Sonoma County went and stood next to all the people from Los Angeles who are paying entrance fees and said, ‘We don’t like it, why should we do it?’ I think they would get an earful,” Laird said. “It’s about balancing interests.”

But Charter said the fee expansion represents a pivotal moment for California. He is among those who view the debate through the prism of social justice.

“Are we going to sit idly by and let the state begin to deny public access, which is really what happens when you throw financial hurdles in the way of families for whom it could serve as a roadblock to have to pay?” he said.

“They simply will not go to the coast, and that changes the whole social dynamic, not just of Sonoma County, but in several counties, because Sonoma is where they come, particularly during hotweather days. All of a sudden, it becomes a place to pay to do just about anything.”

Rosa Rios, Dominguez’s 17-year-daughter, joined Charter and other environmental elders in April at a marathon Santa Rosa meeting of the California Coastal Commission, the influential entity that oversees protection and development of the coast. If the state were to expand day-use fees at beaches, Rios said, it would further limit the family’s options for spending time together — a point echoed throughout the day by park advocates and local elected officials.

“This is one of our favorite options to liberate us from our struggles and problems,” Rios said.

FORCED TO CUT BACK

Four years removed from a scandal that toppled its director amid revelations that $54 million had been hidden by department officials to protect their budget — while dozens of parks were slated to be closed — California’s parks system faces a combination of pressures unrivaled in its 152-year history.

Chronic underfunding, management miscues and a failure to modernize have translated into scaled-back services, shorter public hours, skimpy staffing and visible signs of decay throughout the state’s 1.6 million-acre parks system — the nation’s second largest behind Alaska.

In Sonoma County, cutbacks have closed bathrooms, campgrounds and water fountains in parks. In the nine-county Bay Area, park staffing is down 60 percent since before the recession, with 55 full-time state parks employees covering 28 sites, including eight in central and southern Sonoma County. The ranger corps in that territory has been cut in half since about 2008. More than $80 million in deferred repairs are needed in state parks in Sonoma County, part of a more than $1 billion backlog statewide.

Parks officials say they are seeking to overcome those hurdles, pointing to a coordinated effort in the aftermath of the 2012 scandal to overhaul management and bring park operations into the 21st century. That campaign includes upgrades in technology for visitors and rangers, greater diversity in leaders at the top of the agency and the concerted push to expand andimprove fee collection.

“You’d be hard-pressed to find in our history of state parks an effort that’s been as robust as this,” said Lisa Mangat, who last year became the third director of the California Department of Parks and Recreation since 2012.

Mangat arrived at her post with a background as a budget and fiscal analyst, with virtually no work experience in parks and recreation. She now serves as the top administrator of a system geared to capture more fees from the visiting public to sustain parks.

The controversial push, although not entirely new, gained fresh momentum with a 2012 law seen by parks officials as a mandate to expand fee collection to help offset an ever-shrinking share of the state’s general tax revenue.

Those in Sonoma County who oppose the new beach fees need to consider that context, Mangat says.

Of the 279 sites in the state park system, 171 charge fees. In Sonoma County, including state and county systems, most parks charge fees for day-use and overnight visitors. It is not fair that visitors at parks where fees are charged are subsidizing those who don’t have to, or simply don’t, pay to play, Mangat and other state park officials say.

The parks system collects more than $103 million in visitor fees annually, comprising about 20 percent of its budget.

“This is not a one-off conversation we are having with Sonoma County, but how it fits into the broader scope of the state,” Mangat said in a recent interview at her 14th-floor Sacramento office with sweeping views of the state Capitol.

“We are responsible for 280 parks across the state,” she said. “There is this unprecedented initiative that’s going forward in terms of remodeling ourselves and standing up this kind of new model of stewardship, protection, preservation and interpretation for all people. That’s the overarching vision for California State Parks.”

But others, including local and state representatives, say fundamental change is still a distant dream for the state parks system. Many observers say the overhaul will achieve little if California doesn’t up its commitment to funding parks.

“The bottom line is that we have a state parks system in crisis,” said state Sen. Mike McGuire, a prominent voice among those pushing for more money for parks. He opposes the state’s beach fee plan, which he called a “piecemeal approach” that would deter access for low-income visitors and not fully address parks’ budget woes.

“State parks have been underfunded for years and for too long we as a state have run the system on hope,” McGuire said. “We hope there will be enough corporate donations to keep the gates open. We hope nonprofits will come in and manage state parks. Hope is not a strategy for success.”

Under such pressure, parks — whether from insufficient upkeep and staffing or outright neglect — may fail to live up to the system’s lofty public promise.

“Whether you’re talking about parking lots, bridges, ADA facilities, natural resource management — the gradual defunding of state parks is jeopardizing everything that we’ve built up for the last 150 years,” said Caryl Hart, Regional Parks director for Sonoma County and former chairwoman of the California Parks and Recreation Commission. “There’s no question about it. And you can see that here in Sonoma County.”

STRUGGLE CONTINUES TO GRANT PUBLIC FULL ACCESS TO STATE PARKS

“Hold on. You’re about to come out of your shoelaces.” Craig Anderson was grinning as he steered his hybrid SUV up a steep former logging road above the Russian River, just a few miles inland from the coast. A lush forest of ferns and conifers shaded the way before giving way to a bald ridge, with panoramic views of the emerald hills. Beyond them was the blue sea.

Anderson was showing off a prized, 3,337-acre addition to Sonoma Coast State Park that local taxpayers helped set aside, ponying up nearly $8 million in open space funds in 2005 to support a $21 million purchase.

The deal for the former timber property called for unfettered public access to the site, known as the Willow Creek addition, but more than a decade later this landscape is largely overlooked and seldom visited.

A gate at the entrance is locked, and only about 5,000 people have the permits that give them access. On the warm spring morning Anderson served as guide, the only visitors were a mountain biker and a hiker.

Blame rests with the state, Anderson said. LandPaths, the Santa Rosa-based nonprofit group he leads, agreed to manage the site for three years, until 2008. Last December, they finally pulled out.

LandPaths had spent $1.45 million on watershed restoration, trail maintenance, recreation permits and other projects at Willow Creek. “Not a nickel of that came from state parks,” Anderson said.

“We finally put our hands up and said, ‘Hey guys, we don’t feel we’re being helpful anymore. It’s time to move on to our areas of need and to our own projects,’” he said.

State parks officials said they are working with the county and a different nonprofit group to fully open Willow Creek to the public within a year, pending approval of plans for trails, roads and other amenities. Until then, the site will remain restricted to LandPaths permit holders.

While the majority of the 37,000 acres in Sonoma County in state parks and reserves is open to the public, Willow Creek is one of several properties set aside as parkland but still cordoned off to general access.

Where the public can enter, the strains of constant use and inadequate care show in many parks. They include huge potholes that swallow tires on the road leading to Bodega Head, eroding trails in Annadel State Park in Santa Rosa and the condition of several of the historic buildings in Sonoma, including the Blue Wing Inn, one of the first hotels built in California. It has been closed to the public since 2001 over seismic safety concerns.

Staffing cutbacks and frequent turnover in personnel have also taken their toll on the public experience. There’s only one ranger patrolling Annadel, the 5,000-acre wilderness park at the eastern edge of Santa Rosa that attracts about 12,000 visitors a month. Rangers have little to no time to serve as natural history guides and interpreters for visitors. Instead, they spend what they have for field time in the most popular areas, leaving problems to proliferate in moreremote spots, ranging from homeless camps to illegal trails.

“I’m saddened by it very greatly,” said Bud Getty, 82, whose 42 year career with the parks system ended in 2000 with his retirement as superintendent of what was then the Silverado District, which spanned eight parks in Sonoma and Napa counties, including Jack London and Annadel. A district superintendent now supervises 28 park sites in five Bay Area counties following a 2013 reorganization.

“I hate to think of what the workload is on the superintendent now,” Getty said. “I don’t even think they are able to get to all of the parks in one month.”

Getty recalled days when he wandered campgrounds chatting with visitors. But he said that kind of interaction with visitors is much rarer these days because of staffing levels.

“I bet most of them don’t see a ranger now,” Getty said from his home in Sacramento. “They are all virtual rangers now, sitting in an office behind a computer. The only contact they have with the public is an enforcement issue.”

SONOMA COUNTY’S PRESERVATION EFFORTS

Sonoma County has played a seminal role in the nation’s parks and land preservation movement, which began in the hallowed ground of Yosemite Valley in 1864 with the establishment of the nation’s first state park.

In 1928, 17 of the 43 proposed sites for California’s nascent parks system were in Sonoma County. Sonoma Coast State Park, among the first state parks dedicated in 1934, owes its existence to pioneer coastal families who sold their land to get out from under the crushing financial weight of the Great Depression. County officials threw in the redwood forest at Guerneville’s Armstrong Grove to match $50,000 in state money for the acquisitions.

Over the decades, local preservationists looked to Sacramento as their ally in protecting land they wanted to save from unwanted development.

But preservationists say that stewardship role has been greatly diminished. Insufficient funding, mismanagement and a decade-old moratorium on state parks accepting new lands are all to blame, they say.

“I assume state parks is not a player at this point,” said Bill Keene, general manager of the county’s pioneering, taxpayer-supported Agricultural Preservation and Open Space District. “There’s nothing to lead me to believe they are going to take land anytime soon. There’s only one game in town, and that’s county regional parks.”

Laird, the natural resources secretary, said it will take more funding for the parks department to enable it to resume its lead role in land conservation.

“We recognize there could well be 50 million Californians in the next generation and that we have an obligation to deal with park acquisition and park operations,” he said. “We are not 100 percent sure how we are going to do it, but we recognize that obligation.”

With the state largely on the sidelines with land acquisition, private groups like LandPaths, Sonoma Land Trust and The Wildlands Conservancy have stepped up to own or manage big tracts of open space.

A prime example is Jenner Headlands, purchased with public and private dollars in 2006 with the original intent that it be turned over to the state. That never happened. More than a decade later, The Wildlands Conservancy is slated to open the property next year to the public. Plans call for free access.

Other nonprofit groups have stepped up to assume responsibility for interpretive programs or to take over day-to-day management of state parks in the county.

A nonprofit’s deal to assume management of Jack London State Historic Park was the first of its kind under a law that sought to prevent parks from being closed in the wake of the state’s budget crisis.

Similar deals now exist for Austin Creek State Recreation Area and Sugarloaf Ridge. The partnerships have kept the gates open. But as with state parks, there are concerns about the long-term sustainability of outside groups, which generate revenue largely through fees, contributed income and venue rentals and are subject to similar fluctuations in funding.

State parks officials also have raised concerns with the nonprofit managers of Sugarloaf and Jack London about commercial activity and visitor attractions, including a highly popular summer concert series, potentially harming park resources.

Representatives for the nonprofit operators acknowledge challenges working within state guidelines while voicing hope the shared operating model will continue.

“Both sides are really just trying to figure out how to work together,” said Richard Dale, executive director of the Sonoma Ecology Center, which is a member of the coalition that runs Sugarloaf. “I feel like there are some things we can do better, and I feel there are some things parks can do better. But I’m pretty positive about the relationship.”

TRIONE-ANNADEL STATE PARK

Toraj Soltani hammered on the pedals of his mountain bike as he powered up a steep fire road in Annadel State Park. He and two buddies had hooked up after work on a Friday evening in May to ride the forested open space before nightfall, a lung-busting journey that would take them from Santa Rosa to Kenwood and back.

Soltani, 51, a lifelong Santa Rosa resident, grew up exploring the trails in Annadel. It was to be a housing development, but Sonoma County financier and philanthropist Henry Trione stepped in with more than $1 million of his own money in 1969 to complete a $5 million purchase that handed the property over to the state. When Annadel was slated to close in 2012 amid state parks’ fiscal crisis, Trione ponied up $100,000 to help keep it open under county administration.

The park remains an urban gem, beloved by trail runners, mountain bikers and equestrians. Soltani, the owner of Mac’s Deli in downtown Santa Rosa and a well-known local cyclist, paused briefly on his ride to share his memories of hiking at Annadel with his mother. Several years ago, Soltani and his wife bought a home near Annadel so the family could have easy access to the park.

“It’s so woven into our lifestyle,” he said. “We hold it very dear.”

But Annadel also serves as a prime example of the pressures and failures besetting the state parks system. It suffers from its own popularity, attracting an estimated 120,000 visitors annually. On weekends, it is not unusual to see horse riders, cyclists and others on foot squeezing onto the same paths. Many of those trails are in dire need of maintenance, with erosion from wear and tear and weather taking a clear toll over the years. At the same time, a widening number of trails are unsanctioned, carved out mostly by renegade bikers exploring terrain that established paths skirt. Homeless encampments also have sprouted in some areas of the park.

Volunteer patrols fan out on horseback and bikes on weekends to monitor use, but the sight of a ranger is exceptionally rare. Soltani, who typically rides in Annadel several times a week, said he hardly ever sees a ranger in the park. Two are assigned to Annadel, with only one on duty at a time to handle administrative and interpretation roles while also patrolling the 5,000-acre area.

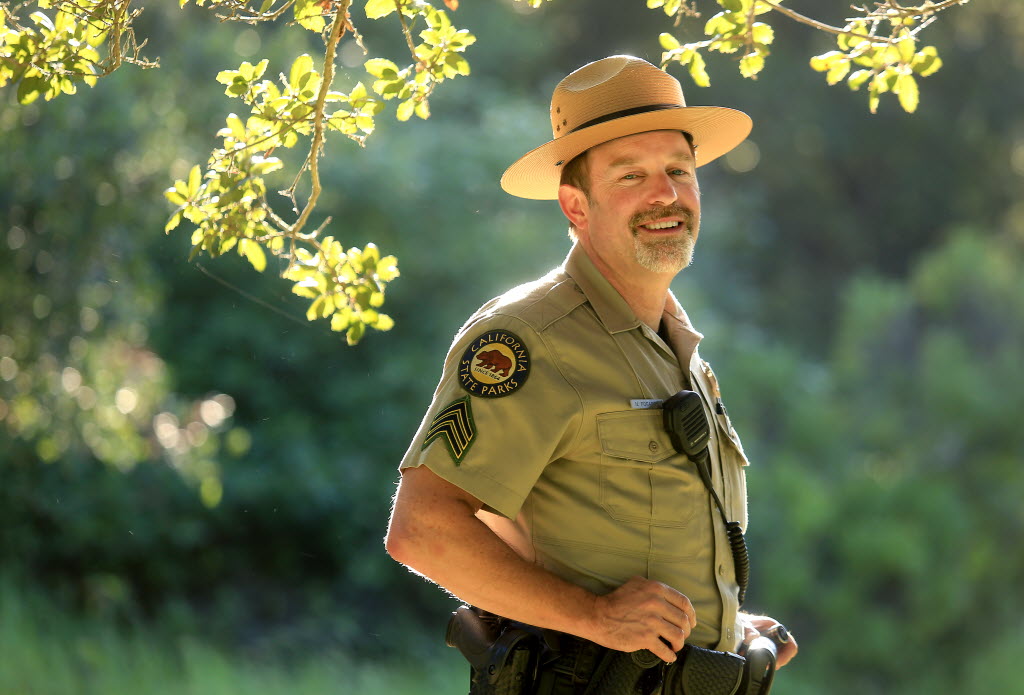

“I think it’s like that around the department, where each person is probably doing the job of three or four people,” said Neill Fogarty, the supervising park ranger for Annadel.

Around 2008 there were 12 rangers assigned to the sector encompassing Annadel and four other parks in central and southern Sonoma County and Napa, Fogarty said. Now there are six, with only three specifically assigned to patrol duties. Rangers are no longer staffed at Jack London or Sugarloaf because of the operating agreements with nonprofits, which rely on volunteers or local police to handle public safety emergencies.

Fogarty said protecting the park’s sensitive landscape while meeting the public’s demand to play at Annadel is a difficult balancing act.

“A lot of people want to get out and have fun and use it today, and in some cases, there’s not a lot of thought about what Annadel will be 100 years from now, and whether it will be crisscrossed with illegal trails,” he said.

The park faces chronic budget challenges, stemming in part from the state’s inability to capture revenue from park users. Most visitors park outside the official Channel Drive entrance and walk or bike in to avoid paying the $7 day-use fee. Others set out from neighborhood entrances or from adjacent Spring Lake Regional Park, overseen by the county.

Visitors to Annadel are supposed to pay using a self-pay station commonly known as an iron ranger. Fogarty said an automated machine that will allow visitors to pay using credit or debit cards is on order.

“I joke with people who come in that soon we’re going to enter the 1980s and give people more options to pay. For now, it’s cash and check,” Fogarty said.

On the Friday night Soltani and his friends were out for a ride, the informal gravel lots on Channel Drive were nearly filled with vehicles. In the sanctioned lot, past the self-pay station, a single car was parked. It belonged to Will and Amanda Rien, a young Texas couple who’ve made Annadel a frequent hiking destination since moving to Santa Rosa a little more than a year ago.

Will Rien, a contract online retail worker, said the fee to use Annadel is not an insignificant amount to pay given the couple’s modest income. He said they do so out of a sense of moral obligation, and because it’s cheaper than a gym membership.

“I paid state taxes this year for the first time in my life. We don’t have those in Texas,” he said. “It makes me feel better to pay knowing that some of that money is going to state parks.”

PUBLIC FUNDING NECESSARY TO SUSTAIN THE VISION OF STATE PARKS

It will take public money to salvage and sustain the vision of state parks. On that point, there is little disagreement. But finding that money is difficult in a state searching for funds to support other core needs, including transportation, education, criminal justice, health care and water supply.

Balancing these competing demands is challenging, said Laird, a three-term Central Coast assemblyman who was appointed secretary for natural resources in 2011 by Brown. He noted there is no minimum level of funding mandated for state parks in California, which means the system is vulnerable to cuts.

“I think every state park system has challenges that are similar to California’s,” he said. But voter-approved guarantees for education funding — which takes up half the state budget — and big-ticket spending on transportation and prisons affect what remains for parks.

“There is a limited part of the budget that is discretionary and parks is in that,” Laird said. “When there is an economic downturn, you go to the discretionary part of the budget first, and that’s been a challenge for state parks.”

Among state park systems nationwide, California’s system takes in the largest amount of revenue from visitors, concessions and other contracts. In the fiscal year that ended in mid-2015, that sum was $122 million, more than 20 percent of the agency’s budget.

But ranked on a per capita and per acre basis, California’s park revenue falls to the middle of the pack among state systems, according to a 2013 report for the Senate and Assembly committees overseeing the parks department.

Given the volatility of the state budget and other challenges, that revenue generation needs to improve, Laird said. “You have to be more entrepreneurial given these circumstances. It means partnerships, it means different kinds of fee collection. It means different kinds of contracts to run things. It just means trying to figure out how to raise enough money to have parks run adequately.”

The California State Parks Foundation has stepped in to raise $246 million to support state parks.

The system’s future hinges on embracing technology, updating management practices and partnering with private entities to jointly operate sites, foundation president Elizabeth Goldstein said, citing operating agreements with nonprofits to run several parks in Sonoma County as examples. She said new sources of public funding for parks must be identified, but she cautioned against the expansion of day-use fees, saying their implementation must be weighed against the risk of turning people away from the gates.

“There absolutely has to be a public funding source for a long time, or we’re going to be leaning on increased revenues to keep body and soul together,” said Goldstein, who has been at the helm of the foundation since 2004.

California voters, however, have rejected tax increases to support state parks, even as the state has shifted general tax funding away from the system. Today, the department’s share of the general fund is a third of what it was in 1980.

That year marked the start of a decade when the state began putting off repairs to roofs, bathrooms, roads, water and sewer systems, trails and other park infrastructure to cut expenses, according to state officials.

The deferred repairs now total $1.3 billion. That is roughly double the department’s annual budget.

The governor’s proposed budget for this fiscal year includes $60 million to address deferred maintenance needs.

Park supporters are hoping to qualify a ballot measure in November that would earmark $2.98 billion for state parks and other outdoor programs. A marijuana legalization measure that is also expected to be on the ballot would set aside millions of dollars for parks.

McGuire, the North Coast state senator and former Sonoma County supervisor, introduced legislation this year that would establish a 15 percent sales tax statewide on medical marijuana, with 20 percent of the proceeds steered toward state parks for deferred maintenance costs. The cut for state parks conservatively would amount to more than $20 million annually, McGuire said.

“We’re at a tipping point,” he said. “We’ve spent billions to protect some of the most pristine open space woodlands and watersheds over the last many decades, and all of that investment is starting to crumble.”

Hart, Sonoma County Regional Parks director, agreed that public funding is critical to the turnaround of state parks. But she also said the state could be saving more money by partnering with local agencies to manage parks, citing Annadel as an example.

The state spends about $670,000 annually to operate Annadel State Park. The county, which took over management of Annadel in 2012 to keep it open, operated it for half that amount.

But negotiations to extend the deal past the initial year fell apart because the state refused to put up additional money, according to Hart.

“Now it’s costing $300,000 more and the public is getting less,” she said.

In addition, state parks’ centralized command structure continues to stifle innovation, critics say. As an example, they point to Funky Fridays, the popular summer concert series staged by volunteers at Sugarloaf that was forced to move to a county regional park this summer.

State officials expressed concerns the event had become too popular, risking harm to the park’s sensitive natural resources. But now the park will go without that source of revenue.

“I had to hit my head against the wall for years working with state parks to use our services to better their product,” said Anderson at LandPaths. “Time and time again, they tried to fit us in their existing template, but they were very slow to figure out how to use our services in a way that was helpful.”

OPPOSITION TO BEACH FEES AT STATE COASTAL COMMISSION HEARING

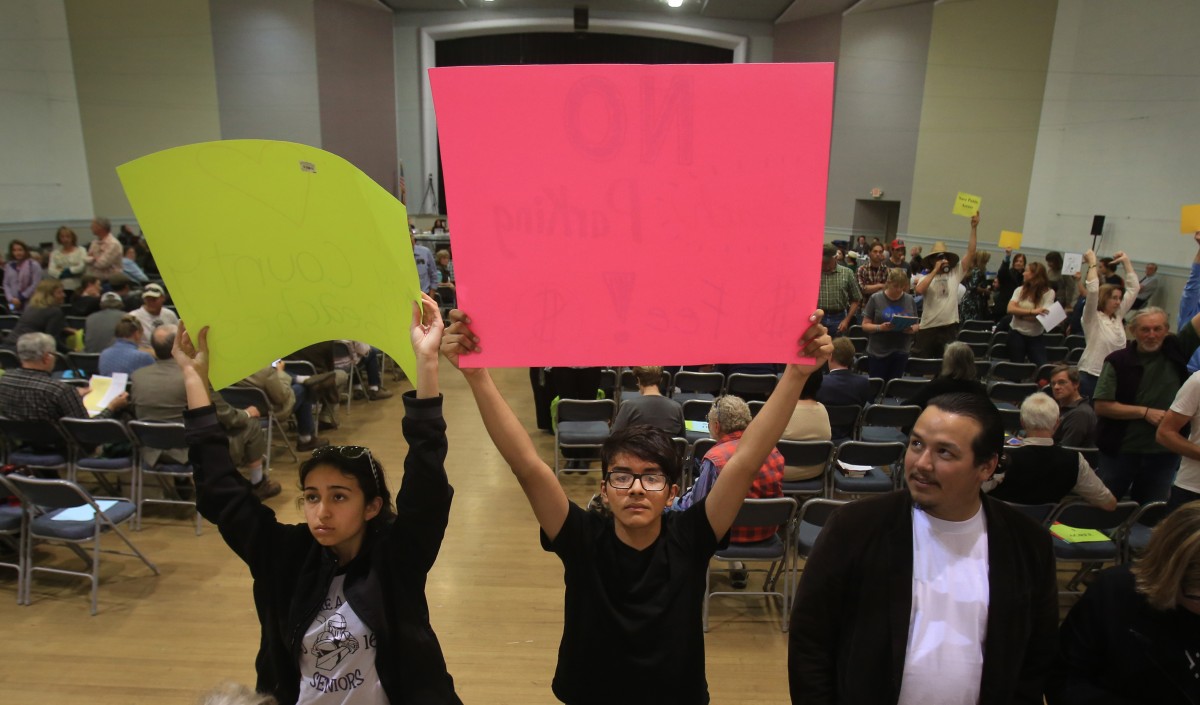

All of the tensions were laid bare at the packed April 13 hearing before the state Coastal Commission that drew more than 500 people to Santa Rosa’s Veterans Memorial Building. Every member of the public who addressed the 12-member commission during the six-hour hearing, including county representatives, opposed the beach fees.

Among the speakers was Lucy Kortum, widow of Bill Kortum, a Sonoma County veterinarian and giant of environmental activism who helped launch and lead the battle to protect public access to the California coast — a movement that spurred creation of the Coastal Commission.

Kortum reminded commissioners of their mission to protect that public access. The fee proposal, she said, presented them with an “opportunity to reinforce it again with a decision that will support not just our local coast plan, but will help citizens of California to experience their coast.”

Rosa Rios, reading from scribbled notes, told commissioners of her family’s economic hardships and said paying to visit a formerly free park site would add to those burdens.

“Isn’t our struggle hard enough already?” Rios said. “Stop expecting us to give money that easily because we cannot. We need our beaches as much as we need our houses.”

Milton Contreras, a 17-year-old classmate of Rios’ at Roseland University Prep, told commissioners the fee proposal was “discriminatory.”

Mangat did not directly address the fee proposal in her remarks to the commission. Instead, the state parks director attempted to broaden the context of the debate.

“We are a 150-year-old system and it is that time when we need to stop and ask ourselves tough questions and kind of refresh ourselves — to make sure that we’re modern and that we’re more reflective of the California of today.”

While she spoke, many in the audience stood and turned their backs. At the end of the day, the commission opted not to rule on the controversial plan, instead continuing the debate to give warring local and state agencies more time to reach consensus. The closely watched standoff was set to return to the commission this summer.

In her Sacramento office a month later, Mangat echoed many of her comments about ongoing change within her agency and the choices she feels Californians must make to ensure state parks are available for future generations. That includes, she said, the public paying more fees to use parks — generating money that could go toward such things as repairing potholes on the roads to Bodega Head and Goat Rock, or to open Willow Creek fully to the public.

“We don’t feel good about those things,” she said of current park conditions on the Sonoma Coast. But being realistic about what they are and finding ways to move forward is the “thrust behind our fee proposal.”

For Maria Dominguez and her family, a day at the beach remains an affordable way to find comfort and inspiration. Following their picnic at North Salmon Creek, she watched the kids scatter and then lay down on a blanket to rest. Soon she was asleep.

Standing at the water’s edge, Rios said she hardly ever sees her mother at such peace. It’s among the reasons she looks forward to coming to the coast.

“We don’t have to worry about the things we have to do or where we have to be,” the teen said. “It’s just a free day.”