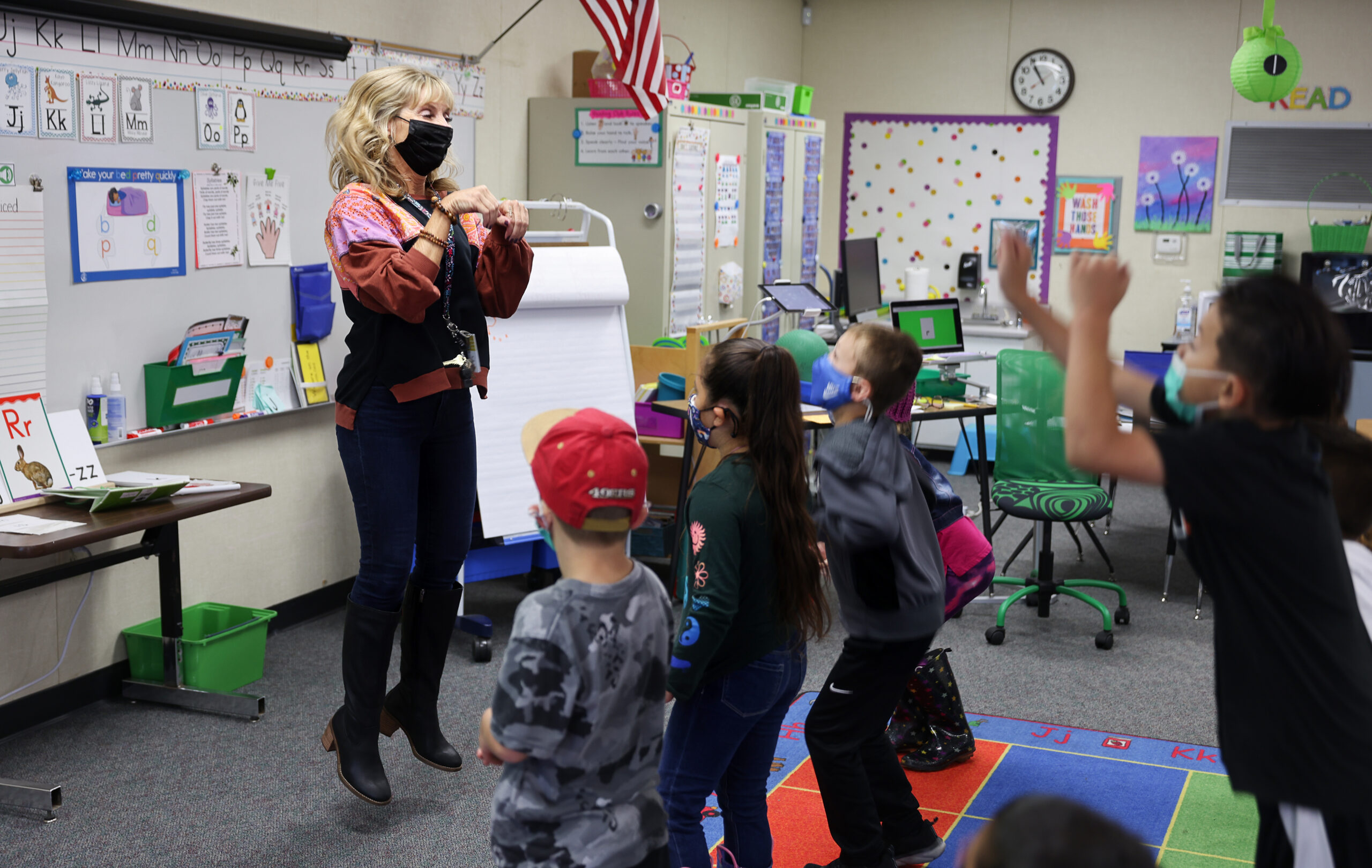

The floor of Jen Grady’s classroom at Mattie Washburn Elementary School was shaking ever so slightly.

On the plush grid of her multicolored carpet, 10 pairs of feet landed with muffled, rhythmic thuds. As the students, all first-graders, hopped, they sounded out the letter “r,” a tricky consonant for many 6- and 7-year-olds to master. But the movement, mimicking a rabbit, held a clue, Grady reminded them. “It’s a developmental thing,” she explains. “They want to say, ‘er.’”

As a reading intervention specialist who has spent 19 years at the K-2 campus in Windsor, Grady’s job is to help students struggling to meet California’s grade level standards in reading and writing. This academic year, that work — and the shared experience for many fellow teachers across Sonoma County — has been an unsettling game of catch-up. “We struggled choosing who was going to get the spots” in her classroom, Grady says. “Because so many of them needed it. Because so many of them are behind.”

The return of nearly all of Sonoma’s 66,450 public school students to classrooms in August was hailed as a pandemic milestone. As a group, they had been stuck at home and consigned mostly to online-based instruction since March 2020, in some cases for months longer than most of their Bay Area peers—the result of stubbornly high local Covid case rates and local public health guidelines that were among the most conservative in the state.

But that period appears to have exacted a steep toll on the education of many students, say parents, teachers, and learning experts, who now find themselves on the front lines of an unprecedented reckoning with the vast and varied academic ground lost to the coronavirus pandemic and its potentially lasting fallout for a generation of children.

In Sonoma County, the pandemic has compounded academic woes in the wake of repeated disasters — wildfires, floods, and power outages — that have erased weeks of instruction across many school districts since 2017. Now, with Covid still a persistent worry on campus and school workforces stretched by staff turnover, educators and families are struggling to determine just how far students have fallen behind.

Schools have disclosed little data from either this school year or last on student proficiency, but officials are focusing on those likely to have struggled most based on pre-existing trends, and the pandemic’s disparate impact on certain communities. That includes Latino students and those from lower-income families, those with parents who have no work-from-home option, foster and homeless youth, and students with disabilities.

“Some of the struggles are those that would have always existed,” says Kitu Jhawar-Terris, a veteran therapist who oversees a local team of school-based counselors. “But now we’re turning the lens, focusing (on) and understanding more of what challenges and struggles students are experiencing.”

Some signs of trouble — academic and behavioral — have been different this year: Students and educators describe eerily silent classrooms filled with children hesitant to speak up; first and second-graders who struggle to hold a pencil correctly; and, on many campuses, a marked increase in referrals to the principal’s office.

Now, the race is on in classrooms across the county to identify and reach those who fell farthest behind. More than $228 million in state and federal aid has been funneled to local districts to launch new tutoring programs, deploy teams of school therapists, and introduce lessons geared to social and emotional health.

The concern spans all grade levels. Parents of young children fret about the setback in foundational learning, while older students have less time to make up for losses. “I think, historically, the kids that did OK are going to continue to do OK,” says Rhianna Casesa, a professor in Sonoma State University’s elementary education department. “The kids that historically didn’t do OK even pre-pandemic — so, you know, our students of color, our emergent bilinguals, our students from low socioeconomic backgrounds — they will continue to not be OK.”

Jeanelle Payne says she has been unsettled by the silence that’s taken hold in some of her history classes this year at Montgomery High School. The students talk little, if at all. She asked fellow teachers if they were witnessing the same thing.

They were, says Payne, a 17-year classroom veteran. Students were struggling to break down large assignments into small tasks or were not working well with a partner or in a group. Many teens showed an extreme reluctance to participate in class discussions. “I am seeing withdrawn students, disengaged students. Students who don’t know how to be a student anymore,” says Payne. It is as if some of her students “fell into their screens and they haven’t come out yet,” she says.

Students say they feel the differences, too. For Daniel Garcia, a junior attending Roseland University Prep, the contrast with his freshman year is night and day. “Now that we’re back in school … nobody says anything,” he notes.

The upheaval in the county’s academic calendar can be traced back several consecutive years before the pandemic. It began in 2017, when, a few weeks into the school year, a historic firestorm tore through the North Bay, burning several campuses and 5,300 Sonoma County homes, displacing thousands of families and killing 40 people. More wildfires, inescapable smoke, destructive floods, and debilitating power shut-offs and outages have since added to the tally of missed days.

Students in Santa Rosa, the north county and the west county have missed out on the most instruction in the past five years, according to data provided by the Sonoma County Office of Education. Geyserville Unified School District closed for 33 days between fall 2017 and November 2021. Guerneville School District closed for 32 days, followed by Santa Rosa City Schools and Kenwood School District, both at 31 days. Mark West Union, Piner-Olivet Union, and Rincon Valley Union School District all closed for 25 days.

“We’ve been here before, especially in Sonoma County,” Payne says on the losses that preceded the pandemic. “So, on the one hand, yes, I’ve led students through trauma before.”

But to hear local students, teachers and mental health professionals tell it, the pandemic has traumatized students on a different scale. Hania Nazario, a kindergarten student at Cesar Chavez Language Academy in Santa Rosa, missed only a month of day care at the start of the pandemic. She returned, but with only four other children. So when she started kindergarten in August 2021 at Cesar Chavez, she was overwhelmed and withdrawn, say her parents, Xavier and Karolina Nazario. “The first few days were rough,” Karolina says. “She said it looked like there were a hundred backpacks outside and that was very scary.”

Stephanie Manieri, programs director for Latino Service Providers, a nonprofit serving the county’s Latino residents, described strain among teenagers she works with in the Youth Promotores program. “I’m seeing symptoms of burnout, and I don’t use that term loosely,” says Manieri, an elected board trustee for Santa Rosa City Schools. “They’re really tired and exhausted and unmotivated, and it’s not because they’re receiving no support. It’s just because they haven’t had a proper break, and they haven’t had stability in such a long time.”

Jhawar-Terris, the therapist, says she and members of the school mental health team she oversees with nonprofit Social Advocates for Youth are treating students struggling with the effects of isolation. “Those students who were really excited to go back to school are now experiencing some of that social isolation, even though they’re around friends; they’re around other people,” she says. “They almost have to relearn how to maintain those friendships in person.”

Face masks required in the classroom, while a necessary health protocol, can make it harder for people on campus to connect, say Payne and Garcia. “Sometimes when somebody is talking, their voice is low and muffled by their mask, and it makes it really hard to hear,” Garcia explains.

“It’s also hard with the masks to read faces,” Payne says. “Does this blank stare mean, ‘I don’t understand. Can you ask it in a different way?’ or, ‘I’m physically here, but mentally I’m somewhere else and I don’t care about this’?”

Students and educators describe eerily silent classrooms filled with children hesitant to speak up, first- and second-graders who struggle to hold a pencil correctly and, on many campuses, a marked increase in referrals to the principal’s office.

In Santa Rosa, Sonoma County’s largest school district, officials have had little to show to gauge the breadth and depth of pandemic-era academic loss for students.

The cycle of tests and periodic assessments schools regularly use to measure and track student development was mostly paused while classrooms were closed, and reintroduced in scaled-back form once they returned. Little if any of that data for local schools has been made available. “We know we have students we need to assist in some learning gaps,” says Anna Trunnell, superintendent of Santa Rosa City Schools. “And through this year, we’re trying to find ways we can assist with intervention and additional support.”

Annual reports called summative assessments, revived by the state and federal government this past spring after a hiatus in 2020, were intended to shed some insight into what progress Sonoma County students made toward grade-level standards during distance learning. “There was some concern, with the suspension of testing in 2020, (that) if that was done again, there’s two years without data,” says Jennie Snyder, deputy superintendent of educational support services for the county Office of Education.

Santa Rosa City Schools, with nearly 15,000 students enrolled this year across 25 campuses, used two online assessments to monitor students’ proficiency in math and English language arts, says Kimberlee Armstrong, associate superintendent of educational services.

Third- through sixth-graders in the district were assessed using tests from a vendor called Let’s Go Learn, while seventh- through 12th-graders took tests from Illuminate Education, a data and assessment platform. Some students took the tests online from home, while others tested in person when the district began bringing students back to campuses part-time in April. As of November, the district had yet to aggregate or release school- and district-wide data from those assessments.

Sonoma County’s public school families had waited with excitement and frustration for the reopening of classrooms. Resentment had grown, too, over several months, as students in neighboring counties returned to in-person instruction earlier in the school year.

Several Marin County school districts, for example, reopened campuses for a mix of in-person and remote instruction beginning as far back as the fall of 2020, after the county moved into the second-most restrictive tier on the state’s Covid-monitoring system. Many in San Rafael were able to attend school full time in person by March 2021.

Likewise, Napa Valley Unified School District, which serves 17,240 students, returned to part-time in-person instruction beginning in October 2020 as the county moved into a less restrictive state tier. Sonoma County, meanwhile, remained stuck in the most restrictive category of operations until the state did away with that system in June.

For three weeks in November, Sonoma magazine sought access to data from Santa Rosa City Schools about student performance, including numbers that would show how different student groups fared in assessments and shed light on known disparities between different ethnic groups and socioeconomic backgrounds.

District officials initially provided some data on 11th grade math and reading proficiency, broken down by school, but later said the dataset was inaccurate because it did not capture the entire population of 11th-graders who took the test. A similar snapshot

the district provided of seventh-grader data included several who were listed as students of the district’s high schools. Sonoma magazine opted not to use the data because of its apparent errors.

Trunnell and Armstrong say the district’s migration to a new student data management system over the summer complicated the data retrieval. As of mid-November, the school board had not yet reviewed any assessment data from the previous spring.

“I know there’s a lot of interest in seeing that,” says trustee Stephanie Manieri. “I just imagine there’s a lot of things taking priority.”

School districts will need to report their assessment data from spring 2021 to the California Department of Education by Feb.1.

“(Students) are really tired and exhausted and unmotivated, and it’s not because they’re receiving no support … they haven’t had stability in such a long time.” District Trustee Stephanie Manieri

In the meantime, districts are looking to interim assessments, which are smaller-scale evaluations administered to students several times a year. These interim assessments can be more useful, says Armstrong, the Santa Rosa assistant superintendent. They show teachers what grade-level skills their students are retaining or struggling to grasp across a trimester, semester, or year — what Armstrong calls “leading indicators” of student progress. Instructors then have time left in the term to help their students improve on specific skills. “That’s the true way for us to accelerate learning, based on the individual needs of every student,” says Armstrong.

At Mattie Washburn Elementary in Windsor, students were assessed at the start of school to determine their proficiency in grade-level skills. Students who needed the most help catching up were routed to intervention specialists. At the end of the trimester in November, teachers assessed their students again to check on their progress. “We are going to be using that data (as) not only a step in time of how they’re doing, but then to drive our instruction moving forward,” says Mattie Washburn’s principal, Susan Yakich.

In Santa Rosa, district leaders have not required all teachers to administer interim assessments in the past, or even this year, but Armstrong says it’s now “strongly recommending” the practice. Across the district in past years, she says, some teachers had already adopted, on their own, the cycle of short-term check-ins. “That’s great, but it’s not equitable,” Armstrong says.

Two Santa Rosa campuses are also piloting use of one assessment, called MAP, or Measures of Academic Progress, which was created by an Oregon-based nonprofit, the Northwest Evaluation Association. Elsie Allen High School and Hilliard Comstock Middle School teachers will be using the assessments to track their students’ progress throughout this year, Armstrong says.

District officials have their eye on the 2022 school year to potentially deploy new requirements for interim assessments across the school district.

Sonoma County school administrators have often described their efforts in the current school year as “learning acceleration,” rather than remediation or recovery. The distinction is more than parsing words, according to Snyder, the deputy superintendent with the county’s office of education. It denotes a markedly different approach.

Typically, remediation prioritizes catching students up on grade-level skills they lack from the previous year, before moving into content for their current grade. Alternatively, learning acceleration emphasizes lessons and material appropriate for students’ current grade, using assessments to determine which skills from their previous grade the students need to improve. Teachers then build that content into lessons, as well.

“We began to hear in the spring, ‘We’ve got to reteach and remediate,’” Snyder says. “What the research has really shown is that kind of approach actually sets kids back even further.” She was referring to a 2018 report by the nonprofit New Teacher Project, based in New York, that relied on nearly 30,000 student surveys, more than 20,000 work samples, and several thousand assignments and lessons to assess which students made larger gains throughout a school year.

“We saw a promising trend,” the report’s authors conclude. “When we make different choices about how resources are allocated — when all kids get access to grade-appropriate assignments, strong instruction, deep engagement, and high expectations, but particularly when students who start the year behind receive these resources — achievement gaps shrink.”

The application can look different in each classroom. Elizabeth Olah, an English language development specialist at Mattie Washburn, describes her approach as being guided by her students’ engagement with the skills she’s teaching. “I’m using what’s called the push approach,” she says. “I’m trying to push vocab that is more than what they already know, more than what they’re going to come up with on their own. They might have come in very comfortable with short vowel sounds. Now I’m pushing them to think way beyond that, to words that have multiple syllables.”

“Teachers are being asked to do a lot more than they’ve been asked to do in the past … They need more resources so that they can adequately meet their students’ needs. SSU’s Rhianna Casesa

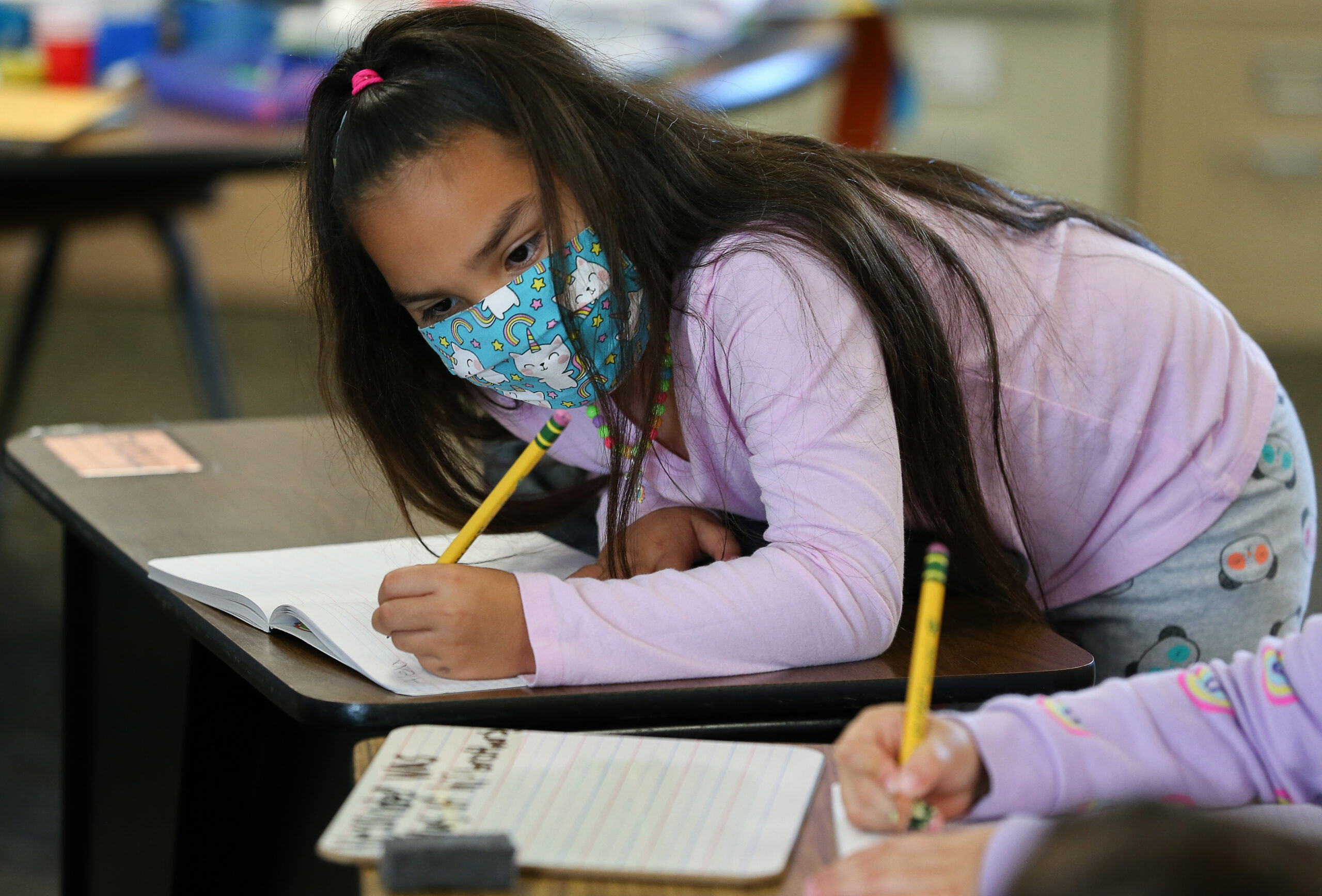

Jimena Mendoza is a second-grader who spends time with Olah each week. Her mother, Yvonne, said she thought the biggest setback for her daughter during the year of distance learning was with her progress in English language. The Mendoza family speaks Spanish and English at home.

But back in the classroom now, with Olah’s help, Jimena is often the first student to speak up when Olah asks her students to read aloud. Jimena even helps her classmates sound out words and sentences.

Students, Olah says, have “tells” when they’re ready to move on from one lesson or skill to another. “In the beginning, it’s too hard,” Olah explains. “And then once they get the hang of it, as a group, it comes too easy and they do it too quickly. And then I know they’re ready for more, and I begin to push.”

Casesa, the SSU professor, says it’s important to remind kids that though they lost skills during the year of distance learning, their schools are striving to help them recover. “If you are a fourth-grader and you’re coming into your first day, and your teacher’s already telling you that you need to catch up, it’s pretty defeating,” she says.

A mother to an elementary-age daughter herself, Casesa encourages parents worried about their children to have faith in educators to address students’ needs—as long as they get the proper support from their districts.

“Teachers have been trained on meeting kids where they are in differentiating instruction, and working with small groups of kids to get them from point A to point B,” Casesa says. “Teachers are being asked to do a lot more than they’ve been asked to do in the past. And so they really need a lot more support, they need classroom aides, they need paid prep time. They need more resources so that they can adequately meet their students’ needs. Because they know what to do.”

Back in Jen Grady’s classroom, Andrew Ceja lay quietly on the floor, carefully writing a lowercase “r” on his whiteboard.

Grady has had to train several first- and even second-graders on how to properly hold a writing utensil this fall, something she has rarely encountered with prior classes over her two decades of work. But Andrew was not one of them. “Because his parents worked on it with him,” she says.

Parents’ involvement in distance learning played a key role in young students’ overall retention of skills, Grady and other teachers across the county say. This year, they’ve seen firsthand the impacts on children who had less support. “Normally, the reading intervention program services kids who … (are) on the cusp of learning,” Grady says. “But now I’m getting a lot of kids that have very (few) skills.”

“A lot of kids’ parents just didn’t know how to help their kids or didn’t have time,” she says. “(It’s) no fault of theirs. As far as distance learning went, parents did the best they could.”

Even with his parents’ support, Andrew entered first grade behind in some kindergarten- level skills, including his ability to blend and segment syllables in a word. To catch up, he spends time outside of his regular classroom with Grady four days a week.

His mother, Yuset, feels distance learning was largely ineffective. As Andrew stayed home with his older sister and brother under Yuset’s supervision, internet connectivity issues and problems logging into Zoom class hampered his lessons most days. Yuset, a stay-at-home mom, would go up and down the stairs of their Windsor home several times each day, checking in on Joe, then an eighth-grader at Windsor Middle School, and KK, then a fourth-grader at Brooks Elementary, in each of their rooms. After that, she would head back to the kitchen table, where she and Andrew would work together on his lessons.

At least one student would usually be in tears at some point during their Zoom lessons. Andrew got stressed, asking her why he had to participate. He struggled to retain reading and math lessons. “It was really tough,” she says.

Yuset had to fill many of his hours each week with supplemental work, teaching him colors and reading to him, she said. But she still was grateful for the ability to do so. “Thank God, every single day I can stay home,” she says. “There were a lot of kids (on Zoom) by themselves.”

Yvonne Mendoza, second-grader Jimena’s mother, was able to bring her children to her parents’ house on the days when both she and her husband needed to work. She bought iPads for Jimena and her brother, Esteban, in fourth grade at Brooks Elementary, so they could have reliable technology to access their schoolwork.

“They got very techie,” Yvonne says. “My daughter was able to screenshot and send me a picture of her assignment. ‘Mom, I’m stuck on this problem.’ I had my phone right next to my computer, and whenever I saw Jimena’s name pop up, I would go to the break room.”

Elizabeth Olah, Jimena’s teacher, saw students dealing with all kinds of situations during the year of distance learning. Sliding her finger down her attendance sheet, she points to the names of a couple of students who spent a month or more in Mexico last year, logging onto their class via Zoom. Several students gave the class online tours of their new quarters. Another student who lived on a farm was regularly accompanied on Zoom by the sounds of cows and other animals.

“There were some definitely difficult situations they had to work through,” Olah says, adding that some students who were left unsupervised would simply stay in bed. “They had their Zoom on, but they were sitting in their bed and they were not getting up and they weren’t getting near the screen and they weren’t participating.”

Xavier Nazario, the father of Cesar Chavez kindergartner Hania and her sister, Zosia, a fourth-grader, voices the same uncertainty shared by other parents and teachers about the pandemic’s long-term fallout for children. “I think the challenging thing is, we don’t know (all) the impacts this pandemic has had,” Nazario says.

The disparities that divide students could widen and the barriers that many face as they grow older could rise, with implications echoing across the rest of their lives. “I don’t think we’ll know until our kids, if they’re fortunate enough, go to college, what type of anxiety they’ll have or how they’ll view the world,” Nazario says.

Some educators, including Olah, are almost defiant in their optimistic outlook. They remain encouraged by the progress they’re seeing students make back in the classroom. “I am very excited to see what happens by the end of the year,” Olah says. “I think we may get there. They’re running from way behind, but they are making up ground and they’re making it up pretty quickly.”

Others, like Montgomery High’s Jeanelle Payne, are still wrestling with doubts about how their students will fare, both now and into the future. “We had high hopes for coming back, but now we’re in it, and it feels like just another year to survive,” she says. “(We have) some who are awesome, and some that are really struggling.”

Some students are bouncing back, “but that’s not everybody.”

“This is just the state of education right now,” she says. “We’re trying to teach academics, but there’s so many other needs.”

Mental Health Support

Now, perhaps more than ever, school leaders have prioritized behavioral health and emotional support initiatives to help with student wellness. The recognition of this need is unfolding on a national scale: in December, the U.S. Surgeon General, Dr. Vivek Murthy, issued an advisory with recommendations to marshal a “swift and coordinated response” to the growing student mental health crisis.

Sonoma County’s 40 public school districts and 56 charter schools were allocated $228.4 million in pandemic-related aid to bring those plans to life. Here are a few examples of ways schools are working to address students’ mental and behavioral health needs:

• In Petaluma schools, Covid money is paying for teacher training to address students’ social and emotional needs and engage their families. The training is just one part of a total $2.2 million geared toward support strategies for learning loss.

• Officials in the Windsor Unified School District allocated nearly $400,000 to professional development on social and emotional learning.

• Santa Rosa in the fall deployed a new social/ emotional assessment tool called Pandora, to gather information from its students on their social and emotional awareness and needs. District staff were set to begin to examine that data in November and December.

• Most districts have launched after-school tutoring in math and English, often with a particular eye toward English language learners, students from low-income households, and foster youth.

• Many schools have also boosted credit recovery options to help secondary students who failed courses during distance learning stay on track to graduate.

Anna Trunnell, superintendent of Santa Rosa City Schools, says plans to support students with pandemic-related issues need to have a perspective extending beyond even this school year. Schools have through September 2024 to spend the last of their federal Covid dollars.

“We know that the shift won’t happen overnight,” Trunnell says.

‘We’ve never felt this invisible’

Not all students returned to the classroom at the start of the school year. April Loveday-Brown, who is disabled and has complex medical needs, is one of them. Each day, her mother, Andrea, logs her onto Zoom to attend classes at Parkside Elementary and receive therapy from home.

Andrea says parents of special education students face an ongoing struggle to get their children enough access to instruction. “We have never felt this invisible. And that’s coming from someone already raising a kid that feels very marginalized in general.”

At the beginning of the current school year, April was only receiving around four hours of instruction and therapy a week. Her mother pushed for three months to get that number up to nearly eight hours.

She wants local families to understand that for students like April, things have not gone back to normal. “The language at the beginning of the pandemic was, ‘We need to take care of our most vulnerable,’” Andrea says. She finds it ironic that now that things are moving forward for so many others, the families of special needs students continue to feel unseen.

Many families in 2020 and 2021 protested the limits of remote learning for children with disabilities, as well as Sonoma County’s months-long delay in bringing special education students back for in-person instruction.

This year, many of those students have returned to their classrooms, says Adam Stein, executive director of Sonoma County’s special education agency.

Stein says he is hearing a mix of positive experiences, especially from families whose children are back in class. But even those families have had tenuous access to services at times.

Staff shortages and the lack of substitute teachers are disproportionately affecting students with disabilities, says Stein. “If you’re a district and you can’t find anyone to step into basic instructional teaching programs, how are you going to find someone who’s going to go into homes? We’ve got great ideas, we’ve got funding. We don’t have any people to provide that (service).”