The moment one walks through the door of Quail & Condor bakery in downtown Healdsburg, a sensual feast begins. The intoxicating, yeasty aromas of just-baked breads rocket straight from nose-to-brain, and then to belly as it responds with a powerful, hungry rumble.

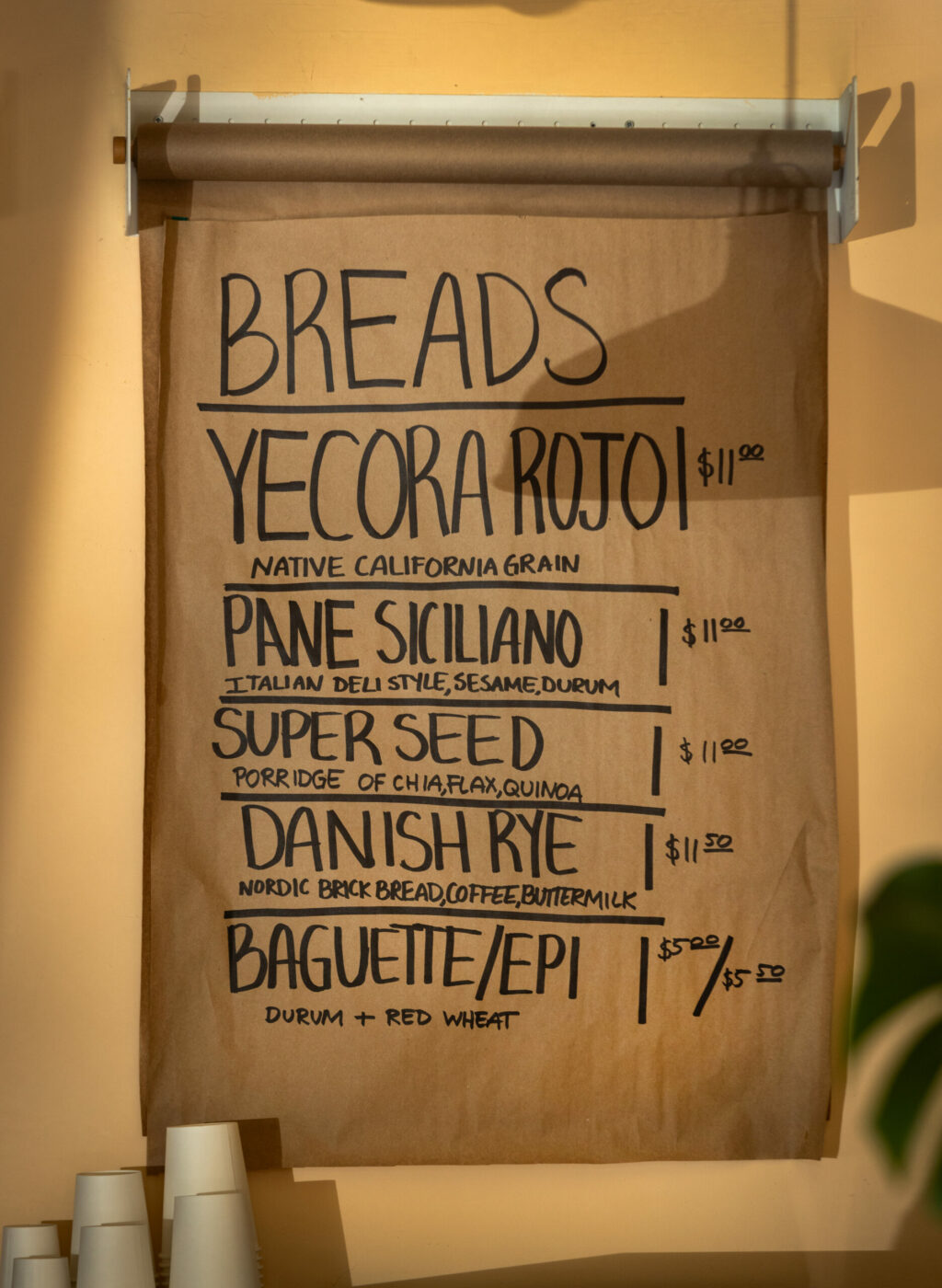

These are no ordinary breads. These are handmade sourdough beauties kissed with startling tang — hearty sesame-seed epis hand-rolled into classic wheat stalk shapes, and slightly sour miche that’s fluffy inside and made with fresh-milled rye, spelt, and whole wheat. The bakery’s naturally leavened baguettes are so sexy, the long, slender loaves look as though they belong tucked alongside a colorful bouquet of flowers in the basket of a bike tootling along the Champs-Élysées.

Quail & Condor caught the attention of The New York Times this past December, putting the tiny shop on the list of “22 of the Best Bakeries Across the U.S. Right Now.” Then, in January, bakery owners Melissa and Sean McGaughey were named as semifinalists for the 2025 James Beard Outstanding Bakery Award.

And yet, as wondrous as the accomplishments are, it can sometimes feel like just another day in Sonoma County — blessed with such a collection of outstanding family-owned bakeries, it might seem an embarrassment of riches.

But that inkling of too much privilege dissipates with that first bite of crunchy-chewy crust on Quail’s pain de campagne, the French country bread crafted with rye and whole wheat, folded in with tart olives, and even more exquisite when slathered with imported French butter.

And that’s just one example. Sonoma County boasts Wild Flour Bread in Freestone; Nightingale Breads in Forestville; Red Bird Bakery in Cotati; Goguette Bread, Village Bakery, and Marla Bakery all in Santa Rosa, and the list goes on. Some specialize in wood-fired brick hearth ovens, some use rack ovens, some work out of home kitchens with cottage licenses. But all unite in one shared cause: to make the finest breads with artisanal flours and grains, wild yeasts, and hands-on love which includes long fermentations.

What is it about Sonoma County that makes it such a hotbed for bread? San Francisco’s sourdough bread is famous, with humidity said to play a crucial role in its fermentation and flavor, but does Sonoma County have its own magical secret factor?

“That’s a really good question,” Melissa McGaughey muses. “There aren’t a ton of grain growers here. For me, it’s about the community and lifestyle, the energy and flow. I’ve only really lived in big cities, so I always thought that the small town of Healdsburg was a stepping-stone for me, but I found that all of Sonoma County is bustling. We’re big, but small — I love that I get to connect with so many people personally.”

Mike Zakowski agrees that it’s the mesmerizing vibe keeps him rooted. He competed for Team USA at the Coupe du Monde de la Boulangerie in Paris in 2012, where the group won a silver medal. He could work anywhere across the globe.

Yet now, with his own The Bejkr business, he sells his mouthwatering goods at the Sonoma Valley Farmers Market year-round on Fridays at Depot Park on First Street West and during summer at the Sonoma Tuesday Night Market.

“I’ve made bread all over the world. I travel and I teach a lot. There’s good bread all over,” he says. “It’s the Sonoma weather that attracted me, actually. I’m from the Midwest originally and I’ve been here 18 years. It’s just such a stunning place to live.”

His breads, all artfully scored, are made of ancient, whole grains, sourced from local farms and stone milled. He mills his own specialty grains, too, such as emmer, spelt, ancient einkorn, California rye, and wheat.

He appreciates that he always finds great reception for even uncommon bread flavors like a loaf he makes with Khorasan (an ancient wheat variety), stone-milled rye, roasted sweet corn, jalapeño, cilantro, and kovasz keszites, a Hungarian-style sourdough starter.

Recently, after a tour of Japan, he’s been experimenting with even more flavors.

“I got reinspired to do some new things, like raisin water, which is an old French technique,” he says. “And I’m a matcha drinker, so I’m exploring green tea powder, adzuki beans, roasted soybeans, mochi, and rice in breads, and I’m making a shokupan now (pillowy-soft Japanese milk bread).”

The fact that so many Sonoma foodies are open to, and eager for, such interesting specialties is a big incentive for creative bakers. For Lee Magner of cult-boutique Sonoma Mountain Breads, that’s been a big selling point keeping him here.

“It’s a community that really celebrates food across the board,” he says, of people who swarm his email to grab the 100 baguettes and 125 or so artisanal loaves he produces each week at his Sonoma Mountain home and farmstand. “Craftsmanship is also really celebrated here, and people understand that making bread is definitely a labor of love.”

The local bread phenomenon was birthed at the turn of the last century, beginning with Franco American Bakery, which started in 1900, making the family-run business the oldest established bakery in the North Bay. The sourdough starter is the same as it was 125 years ago, lovingly nurtured like the precious child it is. It was followed with downtown Healdsburg’s Costeaux French Bakery, founded in 1923, and still wowing with its seeded sourdough and feather-soft brioche.

More beautiful breads blossomed in 1994, when Kathleen Weber introduced us to artisanal loaves made with fine ingredients like organic flours, Brittany sea salt, local extra virgin olive oils, and instead of commercial yeast, a natural starter featuring her own Petaluma ranch-grown grapes.

Initially, she drew on her home-baked, Italian-style fermented fare, baked in a wood-burning oven. By 1995, the French Laundry demanded to be a customer, followed by more high-end restaurants such as Auberge du Soleil. Some might say that the local love truly took flight when Weber opened Della Fattoria in Petaluma in 2003, enchanting customers including Martha Stewart. We lost Weber in 2020, but her legendary breads live on at the restaurant.

Certainly many of Sonoma County’s local bakers could go big time, if they chose. Both Costeaux and Della Fattoria have grown over the years into wholesale businesses. More recently, after outgrowing her home-based baking business, the acclaimed Alexandra Zandvliet opened Sarmentine Organic French Bakery in Santa Rosa in 2021, which was immediately so popular she now has shops in Sebastopol and Petaluma, too.

Yet for many of today’s modern bakeries, keeping small is the point. “For us, the fulfillment doesn’t come from making a bunch of money and growing the business,” McGaughey says. “My husband and I are super-aligned on that. We don’t need to live superlavishly. We are able to pay our bills, put our kids in good schools, and reinvest in the people that we hire so they are able to not only have a career, but also be able to take care of themselves. If there’s anything left over, we are able to take one to two vacations a year.

“We also enjoy very much being able to work with the farmers personally. If we got any bigger, it’d be much harder for us to do that.”

The Bejkr’s Zakowski is a bit more blunt.

“No, none of that interests me,” he says politely, of expanding. “I used to do all that, working with so many bakeries. Been there, done that. I literally do everything myself now, and that’s what I love.”