On the oak-studded hillside behind Sam Sebastiani’s Sonoma home, a rocky path winds uphill, just a stone’s throw from the house itself. Is it a deer trail? A forgotten hiking path?

It’s actually the rustic road that Sam’s grandfather, Samuele Sebastiani, traversed many times a day more than a century ago while hauling cobblestones from the hilltop quarry down to Sonoma Creek for transport to San Francisco. Working at the quarry enabled Samuele to save enough money to build his landmark Sonoma winery, Sebastiani Vineyards, in 1904.

It’s fitting, and eerily coincidental, that 11 decades later, Samuele’s grandson now lives alongside that old quarry road and produces a line of small-batch wines dedicated to the memory of his grandfather.

Sam Sebastiani’s affection for his Italian roots and his wine heritage runs deep, and he revels in surrounding himself with memories of where it all began. Not only is his sprawling home ideally located atop Quarry Hill, but family memorabilia pervades the residence that he, his wife, Robin, and their four dogs have called home since 2008.

Before Sebastiani set eyes on the house, he had recurrent dreams about it. In each of the dreams, he was horseback riding in the hills of his childhood and would come across the house. He was speechless when his real estate agent drove him up to what was — quite literally — the house of his dreams.

“I wanted tranquility, and I wanted privacy,” Sebastiani said. He got it, in spades. The large, single-story Craftsman-style residence was a spec home, so the couple were able to put their own touches on it.

Ceiling panels in the dining room, along with wainscoting throughout the house, are crafted from Sebastiani’s grandfather’s redwood wine barrels. There are paintings of the monastery where Samuele learned to make wine. Hand-carved cask heads from Sebastiani Vineyards flank the dining room window with its spectacular views of Gehricke Canyon.

Since the Sebastianis enjoy cooking — he is renowned in the family for his split-pea soup — there’s a large open kitchen complete with a rack of antique copper pots. Glass pendants collected during a vacation in Venice hang over the island, and the kitchen also features paneling made from Samuele’s wine barrels. The overall effect is that of an Old World Italian kitchen, yet with a touch Samuele could not have seen coming: a dishwasher exclusively for glassware.

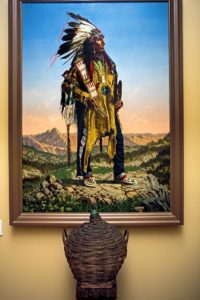

The home’s furnishings are eclectic, a mix of American and Italian heritage pieces. Viticultural touches are everywhere, from the grape cluster lines hammered into the copper wet-bar sink to grape-accent tiles in the wine cellar off the dining room.

The home is filled with the hand-blown Italian glass bottles Sebastiani, 73, has long fancied, along with his extensive duck decoy collection. On one wall is his certificate of knighthood from the Italian government, in recognition of his work to promote Italian grape varieties. Just across from it are his framed Boy Scout merit badges and his Eagle Scout memorabilia. Around the corner are two life-size suits of armor.

Surrounding the home are olive, avocado, citrus and fig trees, Italian cypress and stone pines. Wisteria, clematis and jasmine scramble over arbors and soothing lavender scents waft around the bubbling fountains. Beyond the garden is the hill where the Sebastianis hike with some of their 15 grandchildren.

It’s the same hill, of course, where he spent his boyhood days, when he wasn’t helping out at the family winery, hosing off floors and rolling barrels.

“We lived 200 yards away,” Sebastiani recalled with a chuckle. “I was raised by the old Italians. As soon as you could stay out of trouble, they had you working. Our family code was that if you’re going to give orders, you better have done it.”

When he joined Sebastiani Vineyards full time in 1967, after completing an undergraduate degree and an MBA from Santa Clara University and a two-year stint in the Army, the industry had begun a radical transformation.

“In the 1960s, there was a small movement with a few wine writers,” Sebastiani recalled. “They wanted something to talk about, and it wasn’t jug wines. They were seeking wineries that were making wines with vintage dates and varietal designations.”

So Sebastiani Vineyards joined the Wentes of Livermore, Louis Martini in Sonoma and Napa, and a few others and began the shift away from jug wines. “If you stayed with the Burgundy, Chablis and rosé thing, you were gonna die,” he explained.

So Sebastiani Vineyards joined the Wentes of Livermore, Louis Martini in Sonoma and Napa, and a few others and began the shift away from jug wines. “If you stayed with the Burgundy, Chablis and rosé thing, you were gonna die,” he explained.

After his father, August, died in 1980, Sebastiani assumed the reins at the winery. His mission was to improve quality dramatically. “There was a need to be a standout, not just a player,” he said.

Premium grapes were key, and Sebastiani began his quest with longtime friends and grapegrowers Bob and Fred Kunde in Kenwood. “I negotiated a new contract with quality standards for each part of the ranch,” Sebastiani said. “We put quality standards on each of the varietals. I was ultimately buying every grape off the ranch.”

He also grew his enology staff and bought new equipment. “We proceeded to make some awfully good wines,” he said. “In 1984 and 1985, we won more awards than any winery in America.”

There was friendly rivalry with other winemakers. “Bob Mondavi was one of the greatest competitors in anything he did,” Sebastiani recalled. “He and I got to be good friends because we realized there was room for both valleys and both families. Bob had a knack for surrounding himself with great people.”

Things came to a screeching halt when his mother, Sylvia, abruptly removed him from his position as winery president in 1985, citing concerns about expenditures that Sebastiani deemed necessary.

“I got word that they weren’t happy,” he said simply.

Departing was difficult, but creating a new winery that would embody his vision alone was a tempting alternative. After a long search to find the ideal winery site, Sebastiani and his then-wife, Vicki, opened Viansa Winery & Italian Marketplace in 1989 on a Carneros hilltop south of Sonoma.

“I used to say at Sebastiani that I was trying to create a racehorse out of an elephant,” he explained. “At Viansa, I got to raise a colt to be a racehorse.”

Tapping into his heritage, Sebastiani focused on Italian grape varieties and introduced direct-to-consumer sales and a wine club, rare at the time. He also restored Viansa’s wetlands and created an acclaimed waterfowl preserve — a passion he continues today at Winemaker’s Island, his ranch in Nebraska.

Life was good. “It was a lot of fun,” Sebastiani said. “It didn’t hurt that Italian — quote, unquote — was popular in America. We had an elegant culture to wrap ourselves around.”

Around 2004, as Sebastiani prepared to retire and pass winery duties to his children, a problem arose. Consultants hired by the family said not all the children shared his vision for Viansa’s future. Ultimately, the decision was made to sell the winery.

Walking away from a second winery, one into which he’d poured his heart and soul, was doubly bitter.

“You build it up and then you have to leave it. You start to believe that you’ve got a shadow following you around. If I didn’t have religion, I’d probably be sucking my thumb in a corner somewhere,” he said with a wry laugh.

After picking himself up, Sebastiani realized that he now had an opportunity to be free from the demands of a popular tourist stop like Viansa. “My dream was always to have a small winery where your (goal) was to make the best wine,” he said. “For the first time in my life, I was not stuck with anything. I could get my grapes anywhere.”

For what he calls his “swan song,” Sebastiani returned to the Kunde Ranch, now run by Bob’s son, Keith, for Chardonnay and Sangiovese grapes, and found three great spots in Amador County for Zinfandel, Primitivo and Syrah.

In collaboration with his former Viansa winemaker, Derek Irwin, Sebastiani created his line of La Chertosa wines, limited to around 1,200 cases a year. The wines are named for the monastery in Farneta, Italy, where Samuele learned the art of winemaking. It’s a respectful nod to the grandfather who walked that quarry road so long ago.

It’s also a fitting finale to a life well lived, one spent celebrating family and heritage. In his memento-filled home, Sebastiani is content and at peace. “I live life day to day,” he said. “I’ve stopped thinking about the future and stopped worrying about the past.”