Walter Schug recently gave up driving. His once-efficient, purposeful stride is a bit slower, his hearing a tad less acute, his German-engineered mind not as precise as it once was. It’s what can happen on the cusp of turning 80.

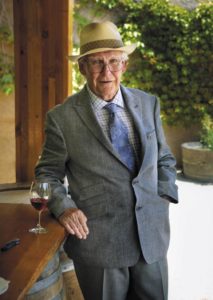

Yet on a hot morning before the start of the 2015 wine grape harvest — Schug’s 60th, 55th in California and 35th in Sonoma — his driver steers his car up the driveway to Schug Carneros Estate, past the flapping flags of the United States, Germany, California and the San Francisco Giants. As he exits the vehicle, Schug dons a jacket and straw fedora, cinches his lavender necktie tight, and heads for the winery he began building in 1989, south of the town of Sonoma. Carneros was a young winegrowing region at the time, yet Schug and his wife, Gertrud, recognized its potential for growing Pinot Noir — and staked their claim.

The exterior of Schug Carneros Estate, with its straight lines, peaked roof and timber framing, looks very much like the winery where Schug grew up, Staatsweingut Assmannshausen, in Germany’s Rhine Valley. It was managed by his father, Ewald, and young Walter romped among the vines, played in the cellar, helped out during harvest when he got older, and absorbed the winemaking dedication imparted by Ewald.

Once inside his own cellar and its cooling aging caves, Schug’s step has extra bounce, his clear blue eyes a twinkle. This is where he is most at home, as he has been for three-fourths of his long, successful life. In a winery, making wine.

“All this equipment, it comes from Germany,” Schug explains with a sweep of his hand. The presses, the pumps, the fermentation tanks, the 669-gallon wood oval casks for the aging of wine — all were manufactured in Germany and shipped to Schug when he began building the winery and planting grapes. “The equipment used in California back then was shit.”

“Back then” includes Schug’s 11 years working for wineries in California’s Central Valley and as a grower relations representative for Modesto’s E. & J. Gallo. In the following years (1972-79), Schug selected the site and helped plant Joseph Phelps Vineyards in St. Helena, where he and his family lived at the time. As the Phelps winemaker, Schug bottled the first varietally labeled Syrah in California and Napa Valley’s first ice wine. In 1974, he produced what was to become one of the most prized and highest-rated Bordeaux-style red blends in America, Insignia, which today commands $225 a bottle. Producing single-vineyard Cabernet Sauvignons from Phelps’ Eisele and Backus vineyards was years ahead of the trend.

Schug’s own Carneros wines, which come from 42 acres of estate grapes and purchased fruit, are made in a firm, crisp, elegant European style. They’re neither super-ripe nor heavy, instead compact and refined, and include Sonoma-grown Chardonnay, Sauvignon Blanc, Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, a full-bodied yet dry sparkling Rouge de Noirs, and a late-harvest Riesling from Lake County grapes. All are superb, yet it’s Pinot Noir that commands Schug’s keenest attention and accounts for 60 percent of his winery’s annual production. You can take the man out of Germany, but not Germany out of the man.

The first wine Schug made for Phelps was Riesling, even though Staatsweingut Assmannshausen was a Pinot Noir specialist, surrounded by Riesling producers. Phelps soon allowed Schug to add Pinot Noir, but the U.S. market wasn’t yet ready for it, and Joseph Phelps Vineyards abandoned the varietal after the

1979 vintage.

“Joe couldn’t sell the Pinot, so I said, ‘Let me see what I can do,’” Schug recalled. “He said yes and didn’t charge me a cent. So in 1980, I began purchasing the same Pinot Noir grapes that had gone into the Phelps wines.”

Schug would work at Phelps through the 1983 harvest, moonlighting as the maker of his family’s wine brand, which launched in 1980.

“I never planned to leave Phelps, but the winery needed the cellar space I was using for my own wines,” he explained. He moved production to an alternate location, then another, and realized there was opportunity on the Sonoma side of Carneros to buy land, plant grapes and build his own facility.

“You get a certain feeling in your body of what Pinot Noir needs, where it wants to grow, where it needs more fog,” he said. “I felt that in Carneros.”

Even at Phelps, owned by Colorado architect Joe Phelps (who died in April at 87), German-made equipment was Schug’s choice, a guarantee, he said, that things would work as expected.

“But Insignia wasn’t intended,” he said. “Once a month, we had a staff tasting of blends of various red-wine components, and someone said of a particular blend, ‘Doesn’t this smell French-y?’ We laughed at the joke. But it happened again the next month. We had Joe taste the wine on one of his visits, and he liked French wine. He said, ‘It’s actually pretty darn good.’ So we bottled it but didn’t know what to call it. I was a proponent of varietal labeling, not blends of varieties, but Joe said, ‘We will call it Insignia.’ He priced it at $20, outrageous at the time.”

It sold like crazy and has ever since.

Steven Spurrier, the British Master of Wine who conducted the now-famous 1976 Judgment of Paris tasting, at which a Napa Valley Cabernet Sauvignon beat France’s Bordeaux wines at their own game, was so intrigued by Insignia, Schug said, “he contacted me to find out how it was done. The 1974 vintage was mostly Cabernet, the 1975 mostly Merlot. We weren’t committed to the same blend each year.”

chug never formally worked at his father’s winery. After six years working in viticulture and winemaking in Germany and England, and earning a diploma from the prestigious Geisenheim institute in the Rheingau region of Germany in 1954, he was invited to serve an internship in Delano, south of Fresno. He rushed home to marry Gertrud in Germany in 1961, and a month later, they put themselves and their Volkswagen Beetle — skis attached — on a boat to New York. From there, they drove to California, where Walter had been offered full-time work by winemakers who had visited him and his father in Germany. He worked for five years for a bulk wine processor in the Central Valley, then was hired by E. & J. Gallo in 1966. With his wife and three children now based in St. Helena, Schug was responsible for managing Gallo’s numerous North Coast grapegrowers. The late Julio Gallo is widely credited with sussing out great North Coast grapes for Gallo’s wines, but Schug was his man on the ground, day to day, wheeling and dealing, and always looking for new fruit sources.

1966. With his wife and three children now based in St. Helena, Schug was responsible for managing Gallo’s numerous North Coast grapegrowers. The late Julio Gallo is widely credited with sussing out great North Coast grapes for Gallo’s wines, but Schug was his man on the ground, day to day, wheeling and dealing, and always looking for new fruit sources.

In the six years Schug worked with Gallo, “He learned all the good spots to plant grapes, and the not so good,” said his son, Axel, now Schug Carneros Estate’s managing partner. “Joe Phelps wanted that knowledge when he hired Dad. Dad would check out the land or vines, tell Joe he wanted it, and Mr. Phelps would write the check. They trusted each other.”

“We never had an argument,” Walter added. “I knew who had what. For example, we were buying Riesling from the Stanton Vineyard (in Yountville, Napa Valley) and it had 12 rows of Cabernet Sauvignon that sold to another winery. I told John Stanton, ‘I want it all.’ ‘They’ll kick your ass,’ he replied. I said, ‘Let ’em kick.’ And I got it all.”

David Graves, who worked for Schug at Phelps in 1979 before co-founding Saintsbury winery in Carneros, has watched the man work for years.

“There is a very sweet side to Walter, an analytical side, a serious side and a knee-slapping sense of humor. He is very proud of his children and grandchildren,” Graves said. “He was well-trained at Geisenheim, and that European perspective informed his entire American winemaking career.”

Despite his achievements, Schug has not sought the spotlight. It doesn’t seem to be in his nature, though he is obviously proud of his work. Perhaps if he’d stayed in Napa Valley, he would be considered more of a superstar than he already is, considering the cachet Napa wines and their makers have. Or maybe if his wines, priced $20 to $50, were as expensive as Insignia now is, he would be seen in a brighter light by those who don’t know his history. No matter.

“I’m just happy we have everything we have,” he said simply.

Can he think of a particularly challenging vintage he’s experienced in California? “No. They’re all fine.”

A particularly great year? “They’ve all been good.”

Schug comes to the winery most days and participates in the blending trials with his right-hand winemaking man, Michael Cox, who has been with Schug Carneros Estate since 1995. Schug’s title is now Winemaster Emeritus.

Gertrud died of cancer in 2007. Axel runs the business side, his sister, Claudia Schuetz, sells Schug wines in Germany, and her twin, Andrea Vonk, is a San Diego CPA who keeps an eye on the financials. When asked if he’d ever consider  selling the winery and vineyards, Walter’s quick response is: “Never.”

selling the winery and vineyards, Walter’s quick response is: “Never.”

At an Oct. 17 dinner at his winery, family, friends and wine club members will help Walter Schug celebrate his many milestones. But he’s not calling it quits.

“Retirement?” he asked. “I don’t know what that is.”

Schug Carneros Estate, 602 Bonneau Road, Sonoma, 707-939-9363, schugwinery.com