Every year, as fire season approaches and winds pick up, Sonoma County residents face renewed worries over the threat of power shut-offs. Meet three families who have taken matters into their own hands with battery storage and solar power, gaining a sense of security that money can’t buy. Plus — What batteries really cost and the smart questions you need to be asking.

Going off the grid has been a fantasy for nearly as long as there’s been a power grid. In the 1970s, just a few hard-core survivalists and rural hermits actually made it happen, riding the wave of the back-tothe- land movement with companies like Ukiah’s Real Goods. Later, green celebs like Daryl Hannah and Ed Begley Jr., made it all sound easy and turned off-grid living into a lifestyle.

Solar power became popular in the late 1990s, and companies such as Tesla, Enphase Energy, and Sonnen started rolling out battery storage units around 2015, allowing homeowners to disconnect from the grid during power outages and create their own temporary microgrid to generate and store their own power, a process known as islanding. But true energy resiliency was still a pipe dream for most.

That all changed here after the fires of 2017.

The local demand for batteries has been so strong since then that Dana Smith, the director of sales at Novato’s SolarCraft, jokes, “We could change our name from SolarCraft to BatteryCraft.”

And Rody Jonas, owner of Healdsburg’s Pure Power Solutions, who has been installing off-grid battery systems for the past 27 years, estimates that so far this year, he’s installed 20 times as many systems as he did in 2017.

According to PG&E, 18 battery storage systems were installed in Sonoma County homes in 2017, increasing to 113 in 2018 and 225 in 2019, says spokesperson Deanna Contreras. And in the unincorporated areas of Sonoma County, 174 battery permits were issued in the first half of 2020, says Domenica Giovannini of the county’s Permit and Resource Management Department.

New solar and battery systems may not live up to the “off-grid” fantasy of the 1970s, but grid-connected homeowners can earn back some costs by selling back excess power. And these systems allow homeowners to go off grid temporarily when they need it most, easing the burden of power shutoff events. In a sense, going off the grid has been replaced by the concept of energy resilience — the ability to withstand natural disaster; the means to harness technology and take matters into your own hands, no longer at the mercy of a utility company.

If the learning curve seems daunting, 26% federal tax credits make it much more enticing. And a new state program, the Self-Generation Incentive Program (SGIP) can offer additional discounts to qualified residents who live in high-fire zones or have been affected by multiple power shut-off events. For those who have questions, Sonoma County’s Energy and Sustainability Division offers free advice and dedicated financing for green energy projects.

The three Sonoma families you’ll meet next all took the plunge into the world of solar and batteries for different reasons, from fire safety, to the cost of connecting a new home to the grid, to a desire for greater resilience. But all say they hope their experiences can convince others to adopt the new technology. As one homeowner puts it: “When you do the math, it’s a no-brainer.”

Jim & Susan Simmons: Off-grid pioneers with a DIY approach

To look at the Kenwood home of Jim and Susan Simmons and then discover their power is fueled by lead-acid batteries is more than just a study in contrasts — it’s a shocking surprise. On the one hand, you have a modern glass-walled dwelling that never needs air-conditioning topped by a wide-hanging, angular steel roof (picture the brim of a Spanish conquistador’s helmet) that also doubles as a cistern to capture water. And yet when Jim Simmons walks out to his barn and lifts the lid on his power storage, all you see are 24 forklift batteries.

“It wasn’t our original plan,” he says with a laugh.

Back in 2011, when they bought the 2-acre property, they intended to hook up to the grid, just as Jim, an architect, did for most of his clients. “I’m not a Birkenstock guy; I like my power,” he says. But when they called PG&E, the power utility quoted them $40,000 just to hook up to the grid.

Keep in mind, this was several years before grid-tied batteries such as the Tesla Powerwall were on anyone’s radar. If not the Jurassic, it was at least the Cretaceous age of battery storage. But at the urging of their two college-age sons, the Simmonses mapped out an off-the-grid system with the help of Mill Valley company Beyond Oil Solar. “The owner allowed us to buy the materials through him and then he recommended the installers. These guys were out of Mendocino and of course their background was pot; they needed the power to grow it.”

After installing an OutBack system with a 24-panel solar array on his barn roof and a storage array of 24 2-volt lead-acid batteries, the total was just over $23,000 after tax credits, and, says Jim, “the best thing is, we’ve never had a PG& E bill.”

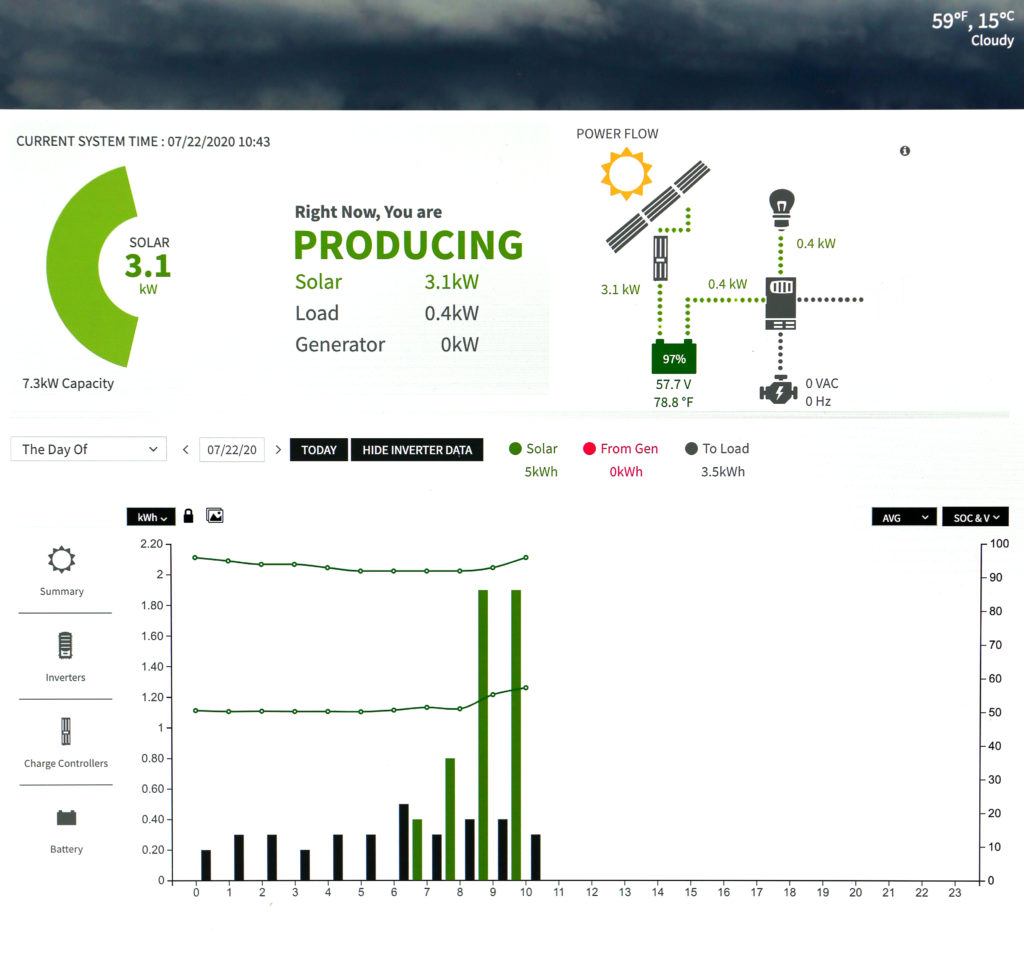

For peace of mind, Jim can look at an app on his phone to see how much solar energy is being generated, check battery levels, and make adjustments, like turning on a back-up generator. The downside to the forklift batteries is that every couple of months, they need to be maintained by opening the tops and adding a cup of water. “You have to be fastidious about it, because if they go dry, that kills that cell,” he says.

In October of 2017, as the Nuns fire scorched Kenwood, the Simmonses’ home became a refuge. “My wife started cooking for people, many who stayed behind to take care of their vineyards because it was right in the middle of harvest. It was a little surreal because you could see fires come over up the mountains. You’d be eating dinner, trying not to choke on the food while watching these poor people’s homes go up in flames.”

These days, a backup propane generator kicks in if the battery drains below 50 percent, but it’s rarely used. Their biggest pull on power are the well pumps, which were installed before they decided on solar and are not as efficient as they could be— something they would fix in retrospect. At this point, they know their improvised system will likely only last about three more years, so they’re already thinking about an upgrade to more modern lithium battery like a Tesla Powerwall.

“Looking back, it was the right thing to do,” Jim says. “If it didn’t work out, we’d be out of some money. But we were looking at such a huge cost otherwise. We decided, ‘Let’s take the risk, let’s take the gamble.”

Bottom Line

Jim and Susan Simmons had a 20-panel, 7.3-kilowatt solar system installed in 2013 and added four more panels in 2015. Their battery is an array of 24 2-volt forklift batteries.

System: $14,811

Battery: $7,500

Installation: $11,133

Total: $33,444

After 30% tax credit: $23,410

Tony DeYoung & Joe Metro: Going solar first, then adding a top-of-the-line battery

Eight years ago, after more than two decades in San Francisco’s Noe Valley, Tony DeYoung and Joe Metro decided they wanted a weekend retreat in the country, one with enough space for their Malinois puppy, Zara, to run around. But after looking at a dozen west county offerings, they still couldn’t find the right spot. On a whim, they asked their real estate agent if they could revisit an Occidental property at nighttime.

It didn’t matter that it was a run-down former pot farm. “We looked up and saw all these stars like you’d never seen,” says Metro, a CFO. “They were so intense.” A half hour later they made an offer. “We were totally clueless,” says DeYoung, a digital marketer turned teacher. “Remember ‘Green Acres’? That was us. We didn’t really know about water and power failures and electric.” But as they started learning more about organic farming, planting blueberries, passion fruit, pluots, and avocados, they knew they also wanted to be green when it came to their remote power supply.

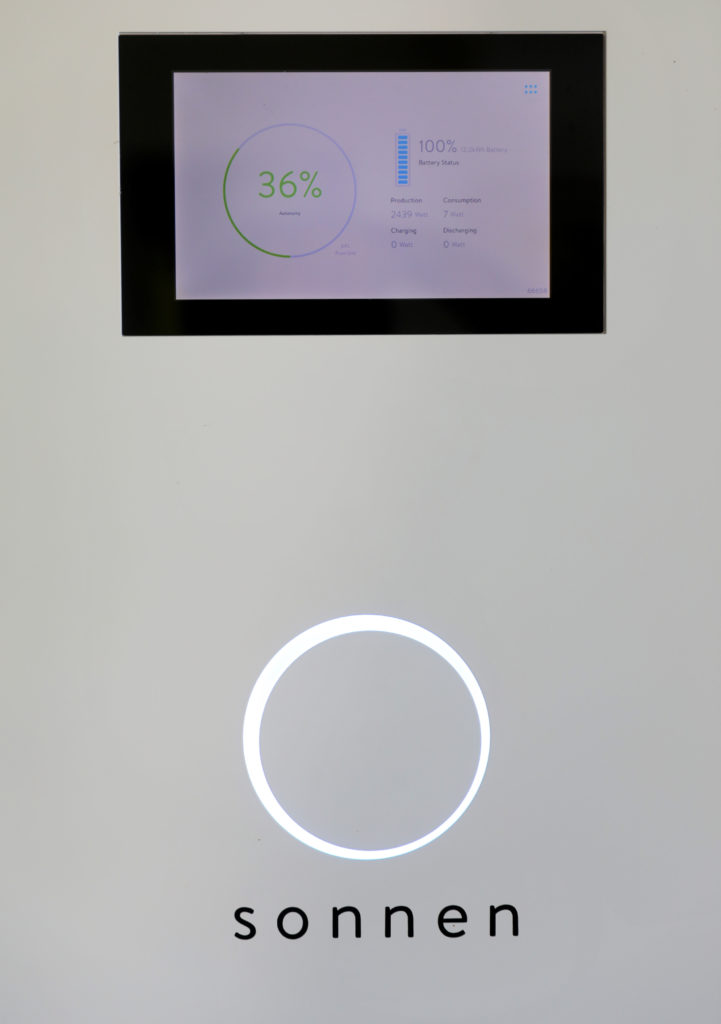

Their 11-acre spread is sandwiched between redwood forest on one side and pastureland on the other. As part of a massive 2015 renovation, the couple installed solar panels on a detached garage. In 2018, when they moved to Occidental full time, they added a German-engineered, American-made Sonnen battery from Sebastopol’s Synergy Solar.

Last year, the house was a beacon of light during the Kincade fire’s power outages. “We were like the local Starbucks,” DeYoung says. “Neighbors would drop by and get a cappuccino, connect to the internet, and we threw in hot showers as a bonus.”

Their 3.36-kilowatt grid-tied system includes a 12-panel array that generates around 20 kilowatt hours of energy during the summer and around 8 kilowatt hours in the winter, Metro says. When they need to cut back on their usage, they shut off their second freezer, switch from desktop to laptop computers, turn off the hot tub, and, when possible, hang their clothes outside to dry.

As early adopters (theirs was only the fifth Sonnen battery installed in the county), DeYoung and Metro weighed all their options, even getting a quote for a new propane generator, which was nearly $25,000 with the cost of a new pipeline and $2,000 a year in maintenance. “Solar was cheaper than that, and there’s zero maintenance and zero noise,” Metro says.

Before going solar, they made sure their home appliances were lean. “The first thing we learned is you have to make your house energy efficient, so now all the lights are LED, we have a superefficient refrigerator, and we added efficient well pumps— so you’re dropping your power footprint,” DeYoung says.

Now, as another fire season is here, DeYoung and Metro prepare for the return of what has become another harbinger of fall: their neighbors’ gas generators buzzing and humming along at all hours during power outages.

Standing in the middle of a ripening fruit farm, surrounded by exotic apple varieties he’s learned to graft, DeYoung says, “What you buy here is you buy quiet. That’s really what you’re buying. I don’t know if you’ve gone into San Francisco lately, but there’s that constant noise, and I think that noise is what’s making people so freaking neurotic.”

“Listen to how quiet it is,” he says, pausing. “That’s why solar and battery makes so much sense. Why ruin that?”

Bottom Line

Joe Metro and Tony DeYoung had a 12-panel, 3.36 kilowatt, grid-tied solar system installed in 2015. They added a 12 kilowatt-hour Sonnen Eco 12 Battery in 2018.

System and installation: $16,000

Battery: $23,000

Total: $39,000

After $3,500 SGIP rebate and 30% tax credit: $24,850

The Weil-Mollard family: A Tubbs rebuild with a solar-powered fire suppression system

“That’s where the fire came over the hill,” says Josh Weil, standing in his front-yard vineyard, looking northwest from his nearly rebuilt Larkfield home.

He’ll never forget that surreal night, nearly three years ago. Working past midnight at Kaiser Permanente in Santa Rosa, the ER doctor called home to warn his wife Claire Mollard of the fast-approaching Tubbs fire. The sky was glowing bright red and flames were only a hundred yards away as she rounded up their 15-yearold daughter, Sophie, and their two dogs and fled the house in less than 15 minutes. Not long after, their house burned down to the chimney.

Somehow their goats, Lucy and Ethel, survived the fire, becoming one of many symbolic stories of resilience in a broken community. But “we lost our cat, Rainbow Bear, which I’m still kind of heartbroken over,” Weil says. “The power was off, and my wife couldn’t see when she ran back into the house to look for the cat. If we had electricity, maybe our cat would still be here. Those things matter.”

Now, three years later, their new home’s fire suppression system, fueled by well booster pumps, will be powered by solar panels and two Tesla Powerwall batteries installed in the garage.

“It’s been a long road getting here,” says Weil, walking past workers as they prep the new driveway before concrete is poured. The T-shirt he’s wearing with a medical cross and the baseball meme “Rub Dirt On It” is an understatement.

The family had solar panels from Pure Power Solutions in Healdsburg installed on their previous 1970s house. They turned to the company again to install a new system, this time with a battery. Weil’s colleague had recently installed Tesla Powerwall batteries in his Skyhawk home and highly recommended them. “I’m a big fan of Tesla and have a Tesla car so it just made sense,” Weil says.

The 27 kilowatt-hour pair of Powerwall batteries cost a little over $24,000 before tax credits. Weil is appealing a decision that rejected his SGIP rebate because his well is also shared by two other neighbors. The 18-panel solar array installed on his garage roof was around $23,000 before tax credits.

Living in a house perched on a hill overlooking Santa Rosa to the southwest, Weil knows it’s not if, but when, another fire breaks out in the region. So having a battery that can disconnect from the grid and keep power running will make “a huge difference,” he says. “Having continuous access to power during a power shut-off is nice. But having it during a fire event when lighting and booster pumps for our fire suppression systems might be the difference between whether or not my family gets out safely.”

The family has lived most of the past three years in a Santa Rosa home offered up by a generous retired surgical colleague. Now, during the Covid-19 pandemic, Sophie and her two siblings, all now in college, are back with the family. Having all three kids around isn’t something Weil and Mollard expected, but the whole family is looking forward to moving back into the new house together. “That will be special,” Weil says.

This time they’re starting out with a clean slate. Everything in the new house is built around efficiency — radiant heating, solar, LED lighting, and state-of-the-art appliances. These features are more expensive at the outset, but Weil chose these them for same reason he bought an electric car soon after they became available. “I do it because I can. But I feel like if I do my part, it helps drive the system and sustain it, and eventually it becomes more available

to other people. So being in the position to lead the way on that, we feel like we’re doing our small part for the world, and we’re hoping to make it more possible for other people down the road.”

And as a doctor, he says, “I’m also thinking about what climate change means for the health of people going forward. Here’s my ability to make a more efficient home and use the power from the sun. It’s just the right thing to do.”

Bottom Line

The Weil-Mollard family has a new 18-panel, 5.9 kilowatt, grid-tied solar system and two Tesla Powerwall batteries that store 27 kilowatt-hours.

System and installation: $23,206

Battery: $24,309

Total: $47,515

After 26% tax credit: $35,160

The family is also applying for SGIP rebates, which should further lower the cost of their system.

How Batteries Work

Sunlight falls on rooftop solar panels made of photovoltaic cells that convert the sun’s energy into DC (direct current) electricity. A line from the solar panel array goes to an inverter, which converts DC to AC (alternating current) electricity for use inside the home. The type of inverter can vary from system to system.

There are also many types of batteries. These days, most large-system batteries are lithium batteries.

The battery connects to the home’s main electrical distribution panel, which supplies power to the house, and to the home’s electrical meter, which both connect to the utility’s power grid.

The inverter and battery also connect to a second electrical panel, commonly called a protected loads panel, which powers crucial appliances during a grid power outage as the system disconnects from the grid and creates its own microgrid. This is called islanding. Within the home’s self-powered microgrid, homeowners can designate power to a well pump, septic pump, lights, Wi-Fi, the garage door opener, and a refrigerator, for example, while switching off power to less critical items such as a pool pump or an air conditioner.

An electric car charger is usually connected the main electrical panel and not to the protected loads panel. That’s because during a power outage, the car could drain battery storage too quickly, leaving other critical electrical needs unmet.

A safety switch automatically prevents solar-generated power from being sent to back to the grid when the grid is down.

And a monitoring system, either hardwired or wireless, allows users to gauge the system’s energy production and battery storage at any time, day or night.

What you need to know about solar power

As the co-owner of Synergy Solar in Sebastopol, Jeff Mathias started out in 2006 building off-grid battery systems in remote areas like Cazadero and the Healdsburg hills. He even installed celebrity chef Guy Fieri’s solar system — the batteries survived the Kincade fire, but the 100-panel solar array didn’t.

While Mathias is currently backlogged at least three months on solar battery-storage installations, he took time out to talk about SGIP rebates, islanding, and how to get educated about solar.

Q: If I’m interested in solar with a battery and I call you and you come out to my house- what happens from there?

A: What I typically do is talk about how solar is really a justification based on a bill. We get a customer’s 12-month PG& E history and we size the system based on that. With that 12-month history we can come to an equation where we say, ‘We’re going to leave you with a $10 minimum charge, but we’re going to eliminate your electric bill basically.’ Most often it’s a dollar-and-cents decision. My main goal with that customer is to set expectations. We sell our systems almost exclusively under what we call protected load panels. Our systems aren’t designed to run the whole house. We don’t want to run the hot tub, we don’t want to run the pool pumps or the air conditioner or even the electric car charger, because if the power goes out at midnight, the whole battery will be transferred to the car. We set the expectation — what do we want?

Q: In addition to tax incentiues, how do people qualify for the equity of resiliency portion of SGIP rebates?

A: It comes down to basic ‘and/or11 logic. If you are in fire zone 2 or 3 OR have had two or more power shut-off events AND you have an electric well that will be on the battery OR you’re on the medical baseline OR you’re low income, then you can qualify for the equity resiliency portion of the SGIP. That’s a rebate of a dollar a watt. So on a Sonnen Eco 20, that’s a $16,650 rebate.

Q: What is “islanding” and what physically happens when there’s a power outage?

A: If we didn’t have islanding, when the power went out, your system would be exporting power to the grid and there would be absolutely no way for PG&E to shut it off and thus no safe way for them to work on the electrical lines that were down. So now, with battery systems, they all have an automated disconnect switch. When it senses the AC system is down, it literally disconnects the house’s system from the grid and then allows the microgrid behind the grid to charge the house.

Q: What’s your best advice for a total newbie?

A: I think the best resource for a customer is to basically look at three vendors, try to get three different technologies, and let the vendors educate. And try to keep it to local and experienced vendors.

You don’t want a salesman who’s only been in business for three months. With three vendors, you’ll get different opinions and different ideas, but you will get educated. To try to find things out on your own is not an easy process.