B Cellars, 400 Silverado Trail, Calistoga, 877-229-9939, bcellars.com. Book ahead for special tasting experiences at this expansive winery off the Silverado Trail and relax on the outdoor patio. Single-vineyard tastings and a production tour and tasting are particularly popular, and the winery has its own chef on hand to showcase the red blends, Syrah, Sangiovese and Petite Sirah with food.

Black Stallion Winery, 4089 Silverado Trail, Napa, 707-227-3250, blackstallionwinery.com. Posh and hospitable, Black Stallion offers luxury and comfort in equal measure, with plenty of outdoor seating to enjoy the winery’s Sauvignon Blanc, Chardonnay, Pinot Noir and Cabernet Sauvignon.

B.R. Cohn Winery & Olive Oil Co., 15000 Highway 12, Glen Ellen, 800-330-4064, brcohn.com. Surrounded by olive trees and meandering gardens, B.R. Cohn is a peaceful place to enjoy a sunny day, taste through Pinot Noir and Cabernet Sauvignon and sample the estate’s own olive oils and vinegars. The lovely grounds are among the most worthy for picnics and afternoon naps, and double as a show ground from time to time for classic cars and founder Bruce Cohn’s summer concerts.

Charles Krug-Peter Mondavi Sr. Family Vineyards, 2800 Main St., St. Helena, 707-967-2200, charleskrug.com. Where Peter and Robert Mondavi first got their start, Charles Krug remains an impressive blend of old and new, with its historical Redwood Cellar now ready for tastings. A prime producer of crisp Sauvignon Blanc and elegant Cabernet, Krug visitors enjoy a slew of tasting options and tours, and can take a bottle and ponder life on the Great Lawn.

Chateau Montelena, 1429 Tubbs Lane, Calistoga, 707-942-5105, chateaumontelena.com. A wonderful place to picnic, with a Chinese garden and lake and views of Mount St. Helena, Chateau Montelena remains a Napa Valley stalwart, the winner of the famous 1976 Judgment of Paris wine tasting and a consistently great producer of elegant Chardonnay and Cabernet Sauvignon. Special tastings and tours abound.

Chateau St. Jean, 8555 Highway 12, Kenwood, 707-833-4134, chateaustjean.com. With a sprawling, picture-perfect lawn, bocce courts and gorgeous location, Chateau St. Jean is also worth a visit as it celebrates the 40th anniversary of Cinq Cepages, its proprietary Bordeaux-style red blend. The tasting room carries many picnic goodies.

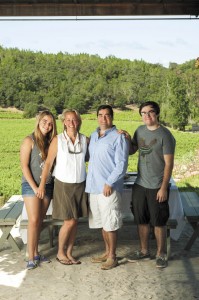

Drew Family Cellars, 9000 Highway 128, Philo, 707-895-9599, drewwines.com. Among the finest producers of Anderson Valley and Mendocino Ridge Pinot Noir and Syrah, family-run Drew operates this small tasting room Thursday through Monday, 11 a.m. to 5 p.m. It’s also just about the only winery in Mendocino County where you’ll find Albarino, a crisp white that’s just right for summer.

Frank Family Vineyards, 1091 Larkmead Lane, Calistoga, 800-574-9463, frankfamilyvineyards.com. Frank Family is a popular Napa Valley stop because of its gardens, picnic spots and affordable tasting fees: $20 for a sampling of four wines, which include sparkling, Chardonnay, Cabernet Sauvignon and age-worthy Petite Sirah. It also happens to inhabit the former Larkmead Winery, third-oldest in the valley.

Freemark Abbey, 3022 St. Helena Highway, St. Helena, 800-963-9698, ext. 3721, freemarkabbey.com. Established in 1886, Freemark Abbey’s winery is a peaceful place to enjoy a classic tasting of a wide range of its wines, or settle in for a one-hour Cabernet Comparison Tasting ($30) that demonstrates the range of vineyard sites sourced for the wines.

Geyser Peak Winery, 2306 Magnolia Drive, Healdsburg, 800-255-9463, geyserpeakwinery.com. This venerable winery has new digs near downtown Healdsburg, after decades of calling Geyserville home. It’s now an easy bike ride from the plaza. Premier tastings start at $10, reserve tastings at $15. Summertime picnic options and seated wine and cheese pairings are also available, by reservation.

Gloria Ferrer, 23555 Highway 121, Sonoma, 707-933-1917, gloriaferrer.com. There may be no better hillside patio from which to take in the Carneros views than the one at Gloria Ferrer, known for its lively sparkling wines. From the sun-soaked deck, enjoy wine flights and bites of cheese and chocolate, or take a tour of the cellar and vines, offered three times a day ($20) with wine. Private food and wine pairing seminars can also be booked for groups.

Goldeneye Winery, 9200 Highway 128, Philo, 800-208-0438, goldeneyewinery.com. The Duckhorn family’s outpost in Anderson Valley, Goldeneye is devoted to Pinot Noir and also produces small amounts of Pinot Gris, Gewürztraminer and Vin Gris of Pinot Noir. Picnic tables in the gardens are available to guests, and tastings of current-release wines are $10 to $20.

Grgich Hills Estate, 1829 St. Helena Highway, Rutherford, 800-532-3057, grgich.com. The mighty Grgich Hills, a producer of wonderful Chardonnay and Cabernet Sauvignon, offers a range of visitor experiences, including barrel tastings every Friday (2 p.m. to 4 p.m.), seated wine tastings with cheese ($40), a rustic vineyard adventure ($125) and grape stomping ($30, Labor Day to Halloween). On any day, box lunches can also be ordered to enjoy on-site.

Gundlach-Bundschu, 2000 Denmark St., Sonoma, 707-938-5277, gunbun.com. This 1860s winery, still family-run, offers a courtyard tasting menu in good weather, with flights of five current-release wines or the option to indulge in five library Cabernet Sauvignons. A board of local cheeses, hummus and almonds might accompany the wines. Vineyard excursions go all summer.

J Vineyards & Winery, 11447 Old Redwood Highway, Healdsburg, 888-594-6326, jwine.com. A glass of bubbly is always a good thing, and this is a well-appointed spot at which to have it, as well as taste J’s Pinot Noirs and Chardonnays. Don’t miss having a sip of Pinot Gris, among its most popular, summertime-perfect wines. The J Bubble Room pairs wines with exquisite, locally sourced dishes; chef Erik Johnson is a huge proponent of sourcing locally.

Jordan Vineyard & Winery, 1474 Alexander Valley Road, Healdsburg, 800-654-1213, jordanwinery.com. By appointment, Jordan welcomes visitors for walking tours through its beautiful compound, which includes the estate’s gardens from which executive chef Todd Knoll sources a cornucopia of produce for winery meals. Tours and seated tastings are available Monday through Saturday throughout the year and on Sundays most of the summer.

Monticello Vineyards, 4242 Big Ranch Road, Napa, 707-253-2802, corleyfamilynapavalley.com. Come to the Corley family’s Napa winery and sit down to a Jefferson House Reserve Tasting ($30) held in the Jefferson House Reserve Room and dig deep into single-vineyard Cabernet Sauvignon. Or sign up to be winemaker for a day ($90), a two-hour blending session and walk through the vineyards that ends with a tasting of more wines.

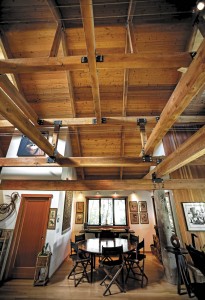

Murphy-Goode Winery, 20 Matheson St., Healdsburg, 800-499-7644, murphygoodewinery.com. Recently refreshed, the Murphy-Goode tasting room feels akin to a redone barn, with ample room to relax, play shuffleboard or linger on the back porch. It also houses a vintage photo booth for taking funny pictures in between sips of wine.

Navarro Vineyards, 5601 Highway 128, Philo, 800-537-9463, navarrowine.com. The wide selection of crisp white wines and bright, mellow reds is worth the drive to Anderson Valley, where Navarro’s homey picnic grounds inspire taking one’s time. Plenty of picnic items are stocked in the tasting room, including winery principal Sarah Cahn Bennett’s fine farmstead goat cheeses made down the road at Pennyroyal Farms. Tours into the vineyard happen twice a day, by appointment.

Patz & Hall’s Sonoma House, 21200 Eighth St. E., Sonoma, 877-265-6700, patzhall.com. In a well-appointed house in the Carneros region, this chic tasting spot showcases Patz & Hall’s single-vineyard Chardonnays and Pinot Noirs. Taste four wines for $25, served with truffle nuts, or go for the sit-down discussion and tasting of six to eight wines with meticulously prepared small plates ($50). Chances are the day will start off with a glass of bubbly.

Ram’s Gate, 28700 Arnold Drive, Sonoma, 707-721-8700, ramsgatewinery.com. Ram’s Gate was designed for lingering, with a host of spacious sitting areas. Then there’s the food, prepared to order by the on-staff chef for seated, guided tastings. Order a picnic lunch to take into the vineyard or out by the pond. The wines alone are a reason to stay, a collection of single-vineyard Pinot Noirs, Syrahs, Chardonnays and even a brut bubbly.

Red Car Wine, 8400 Graton Road, Sebastopol, 707-829-8500, redcarwine.com. Red Car makes fine cool-climate wines, from crisp Chardonnay to nicely rendered Pinot Noir and Syrah. The whimsical labels alone are worth the trip.

Robert Biale Vineyards, 4038 Big Ranch Road, Napa, 707-257-7555, biale.com. A producer of elegant single-vineyard Zinfandels and Petite Sirahs, Biale works with a wide range of old-vine vineyards throughout Napa and Sonoma. Enjoy the outdoor patio and views of the surrounding vineyards while sipping the winery’s signature Black Chicken Napa Valley Zinfandel, an ode to bootlegging in Prohibition days.

Robert Mondavi Winery, 7801 St. Helena Highway, Oakville, 888-766-6328, robertmondaviwinery.com. The place where much of modern Napa Valley tourism began, Mondavi remains a vital place to visit, gorgeously alive and airy. Concerts are hosted on the vast lawn throughout July. Check the website for the schedule.

Rodney Strong Vineyards, 11455 Old Redwood Highway, Healdsburg, 800-678-4763, rodneystrong.com. For a comprehensive taste of Sonoma County with expansive views of vines, look no further than Rodney Strong, which offers an estate wine tasting daily as well as the option to try single-vineyard and reserve wines. From its staunch Alexander Valley Cabernets to Davis Bynum Pinot Noir and Chardonnay, there’s a lot to like. Picnickers are also welcome on the winery’s lawn and vineyard terrace, with food items for purchase inside.

Roederer Estate, 4501 Highway 128, Philo, 707-895-2288, roederestate.com. Take a tour ($6) of the Anderson Valley home of Roederer Estate and see how some of America’s best sparkling wines are made, then sit on the balcony and breathe in the cool coastal air. Picnics for two can be ordered ahead of time for $25.

Schramsberg Vineyards, 1400 Schramsberg Road, Calistoga, 800-877-3623, schramsberg.com. Among the first in California to specialize in sparkling wine, Schramsberg occupies hallowed, historic ground, home to the oldest hillside vineyards in Napa Valley and some of the first caves dug for storing and aging wine. Take a tour (by appointment) and don’t miss the Mirabelle Brut Rosé and other gorgeous sparklers before moving on to taste the J. Davies Estate Cabernet Sauvignon and Pinot Noir.

St. Francis Winery & Vineyards, 100 N. Pythian Road, Santa Rosa, 888-675-9463, stfranciswinery.com. Named the No. 1 U.S. restaurant by Open Table, St. Francis isn’t a restaurant per se but does offer a gourmet food and wine experience, as well as a monthly interactive experience in its tasting room, Sonoma Tastemakers, whereby the best bites from Sonoma producers and purveyors are paired with St. Francis wines. Past months have featured cheese, savory and sweet jams, and pie.

Tamber Bey Vineyards, 1251 Tubbs Lane, Calistoga, 707-942-2100, tamberbey.com. Recently opened, Tamber Bey is located within the grounds of Sundance Ranch, a 22-acre equestrian facility with horses galore and a tasting room fit into a former barn clubhouse. Taste and hang with horses at the same time. Open daily 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. (by appointment) for tours and tastings of Sauvignon Blanc, Chardonnay, Pinot Noir, Merlot and Cabernet Sauvignon.

Tasting Room on the Green, 9050 Windsor Road, Windsor. A partnership of the Deux Amis and Mutt Lynch wineries, this dog-friendly spot pours Zinfandel, Petite Sirah and a red blend called Ducks a Miss, made by Deux Amis winemaker Phyllis Zouzounis. Brenda Lynch’s Mutt Lynch lineup includes Sauvignon Blanc, Merlot and a limited series of vineyard-designate wines under the Man’s Best Friend imprimatur.

Twomey Cellars, 3000 Westside Road, Healdsburg, 800-505-4850, twomey.com. Owned by the same family behind Silver Oak, Twomey specializes in Pinot Noir with two locations, one in Calistoga and this tasting room in Healdsburg, the former site of Roshambo. With beautiful views of Mount St. Helena, the tasting room offers daily sampling of current-release wines, and tours by appointment. House-cured salumi and cheese boards can be ordered ahead of time.