Just north of Railroad Square in Santa Rosa, at Eighth and Davis streets, there’s an elementary school on one corner and a chiropractor’s office on another. Across the street, adjacent to the humming freeway, is a nondescript sand-colored building, a converted warehouse whose outer appearance offers no hint of what’s hidden inside.

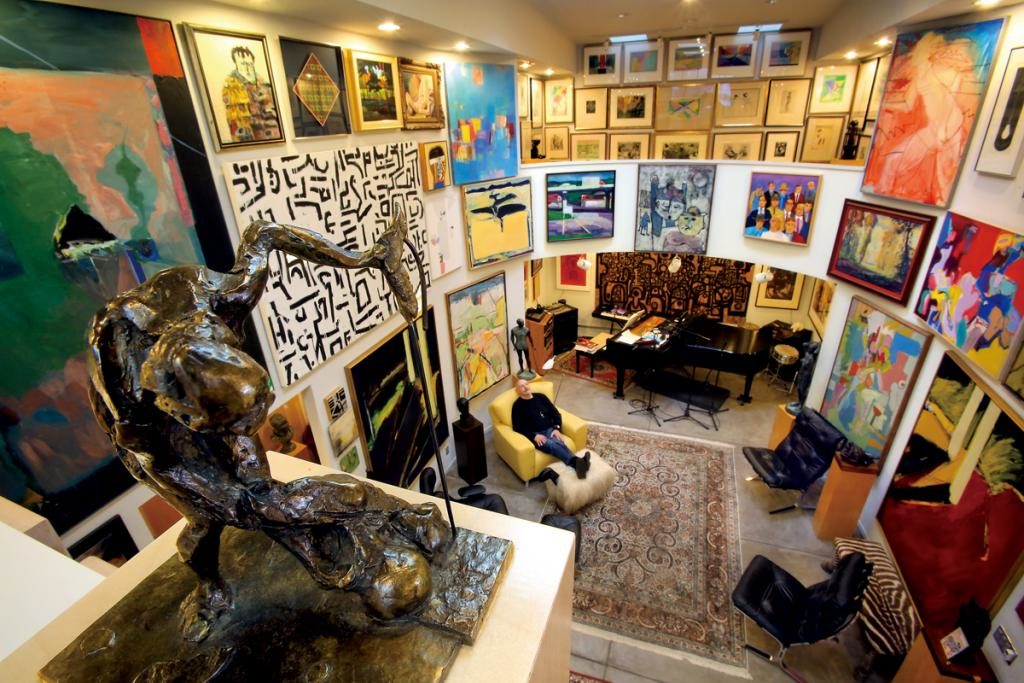

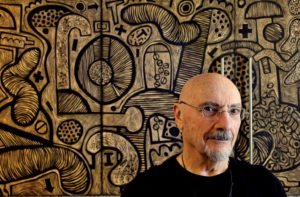

Jack Leissring, 78, an artist and a former owner of the McDonald Mansion in Santa Rosa, has converted the warehouse into a luminous gallery for his wide-ranging, museum-quality art collection. It’s a high-ceilinged, two-story space with a startling variety of paintings, drawings and photographs covering every wall. Yet somehow it doesn’t feel cluttered.

“Almost every extra penny I have I spend on art; the other pennies I spent on women,” Leissring said, then paused and added, “I still have the art.”

Throughout the space are tables with sculptures and busts, many made by artists who have become his friends. Most pieces are by artists who work under the radar, not those celebrated by museums and top galleries.

“Every piece I’ve ever purchased is because of an emotional response,” Leissring explained, tapping a fist to his heart. “There’s a lot of love here; I’m emotionally involved with probably every piece.

“I have some big names, but that’s immaterial to me. This tendency we have to adulate some and ignore others is a tragic flaw.”

Leissring calls the warehouse the “emergency landing field” for his art, “in case I lose my house.” He lives next door to the grand mansion on McDonald Avenue, in its former carriage house, surrounded by his own sculptures and other artwork he’s created.

He purchased the McDonald Mansion in the mid-1970s and sold it in 2005, which he said was a relief. “It was too expensive: I was doing it for the city,” he said. The 19th-century home burned in the late 1970s. Leissring, who’s also a designer, restored it, saying it was “the best toy a boy could ever have.”

He purchased the McDonald Mansion in the mid-1970s and sold it in 2005, which he said was a relief. “It was too expensive: I was doing it for the city,” he said. The 19th-century home burned in the late 1970s. Leissring, who’s also a designer, restored it, saying it was “the best toy a boy could ever have.”

As a 12-year-old living in Milwaukee, Leissring acquired his first painting, in 1947, when the only collections his peers were interested in were baseball cards. A year later he commissioned a painting for the first time.

Leissring’s fascination with art deepened when he began to study the works of Michael Ayrton, a 20th-century English sculptor, painter and author. Leissring calls Ayrton “the most intelligent, loquacious, talented polymath I’ve ever encountered, and I’ve been drawn along a pathway largely due to his influence.”

Winding through the warehouse are rows and rows of shelves containing thousands of art books. They’re organized alphabetically by subject; a random glance takes in large-format tomes about artists including Frida Kahlo, Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, René Magritte and Joan Miró.

Walking through the building, which Leissring completely remodeled about eight years ago, is like traversing a maze. The room dividers and shelves are made of bamboo flooring slats; square skylights large and small evoke a painting by Piet Mondrian.

Etchings are displayed so they can be seen up close. But Leissring says only 2 to 3 percent of the 6,000 to 7,000 items in his collection is visible. Thousands of drawings are housed in wide drawers in the warehouse.

Etchings are displayed so they can be seen up close. But Leissring says only 2 to 3 percent of the 6,000 to 7,000 items in his collection is visible. Thousands of drawings are housed in wide drawers in the warehouse.

Though his art is lovingly displayed, Leissring’s warehouse is not a museum (it’s not open to the public) and it’s not a gallery. But every few months he welcomes visitors for an afternoon viewing because, he said, “Eyes need to see this stuff.”

Some visitors ask him to put up written descriptions next to the artworks, “but I say no,” Leissring said. “That would miss the point of it; either you’re moved by the image or you aren’t.”

Among his most treasured works are paintings and etchings by French cubist Jacques Villon, but Leissring is considering selling his entire collection of Villon’s work, 358 pieces, to help pay the bills. “I’d love to sell it all because I think it belongs together,” he said, adding that the Villon collection is likely worth $1.2 million.

The retired physician, who worked for three decades at Santa Rosa Memorial Hospital as laboratory director, reiterated that he doesn’t buy art to deal it.

“I’ve never bought anything for resale. … It puts art in the position of being commoditized. But I have two pieces of real estate, both with mortgages,” he said, which can’t be covered by his Social Security benefits.

As the impromptu warehouse tour continued and midcentury jazz poured through small speakers in every room, Leissring described a table of heads by the sculptor Jerrold Ballaine. His second-floor desk overlooks his collection like the captain’s wheelhouse on a ship.

As the impromptu warehouse tour continued and midcentury jazz poured through small speakers in every room, Leissring described a table of heads by the sculptor Jerrold Ballaine. His second-floor desk overlooks his collection like the captain’s wheelhouse on a ship.

A mezzotint engraving by Leissring’s grandfather, John Cother Webb, is so precise and realistic that its quality is almost photographic. Near that classic work is a more modern piece, a luridly colored painting called “Wild Dog,” by Mexican artist Rufino Tamayo.

“They don’t have to be of a type to hang together,” Leissring said. “They just have to be good.”

Today, Leissring spends most of his days ensconced in his collection. A true Renaissance man, he arrives at the warehouse early in the morning, draws for an hour or more, then plays piano.

Today, Leissring spends most of his days ensconced in his collection. A true Renaissance man, he arrives at the warehouse early in the morning, draws for an hour or more, then plays piano.

He has published dozens of books about artists he admires through his J.C. Leissring Fine Arts Press. When asked where the books are sold, Leissring exclaimed: “Nobody buys them!” and then conceded some can be purchased online as print-on-demand books.

The warehouse is equipped with a kitchen, washer and dryer, making it move-in ready if Leissring needs to — or chooses to — give up the McDonald carriage house.

Asked if he’s been approached by museums or galleries about his collection, Leissring laughed. “Nobody knows about me. I’m not waving my flag. This is just something I had to do, and I did it.”

Learn more about the Jack Leissring Fine Arts Collection by visiting jclfa.com or jclfineart.com.