built into a mountain comes true.

Matthew Tudor-Jackson affectionately calls his new home “the lair.” He refers to that certain James Bond mystique surrounding his masculine hideaway, set on the lip of a mountain with a wing-like roof that makes it appear as if it could soar over the forested canyon beyond like a large raptor.

While it seems like it’s hundreds of miles off the grid in some ruggedly exotic locale patrolled by eagles, this house is just a 12-minute drive from a Safeway store. And Tudor-Jackson is no villain evading the law, but an artist and designer with a reverence for the warm, free-flowing architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright.

The organic materials, an economic use of space and a deliberate harmony with its natural surroundings captivated Tudor-Jackson the first time he saw this ivy-cloaked house hiding in Los Alamos Canyon, near Santa Rosa’s Hood Mountain.

“When I first came up here I totally fell in love,” he said. “You feel like you’re completely out in the boonies, like you’re going to run into a moose.”

It was no coincidence that the house, to Tudor-Jackson’s eye, had a come-hither look. The two-bedroom, two-bath home was designed by Gary Tucker. As a young student of architecture at UC Berkeley in the 1950s, Tucker spent a year as an apprentice at Wright’s headquarters in Wisconsin and Arizona, Taliesin East and West.

Tucker was turned on to Wright, regarded by the American Institute of Architects as the greatest U.S. architect of all time, when he was a high school student in Southern California.

“I was sitting in the waiting room of a doctor’s office and picked up a copy of some home magazine and there was a freshly minted picture of Fallingwater in Pennsylvania,” Tucker said, referring to the home breathtakingly cantilevered over a waterfall that is one of Wright’s most recognizable works. “I saw that house and decided that’s what I wanted to be. I spent a lot of time in the library reading up on his work and finally decided after I graduated that I would go and interview with him.”

Apprentices met directly with the master, who by then was at the end of his life. Wright died a year after Tucker completed his internship in 1958.

“You interviewed with Mr. Wright and if he liked what he saw in you and your work, you were accepted,” Tucker recalled. “He was so brilliant as a designer that for young architectural students who were inclined to that kind of work, it was nirvana working with him.”

Tucker went on to establish his own practice in Marin County before moving north in 1977 to Sonoma County. He designed many homes in breathtaking locations with dramatic geometric lines. For a home at Timber Cove, he created a long, narrow walkway that cantilevers in a heart-stopping way, out over the rocky cliff. A house on a golf course in Santa Rosa has curvaceous walls and pyramid roofs.

He relishes the challenge of difficult sites, as was the case with the property in Los Alamos Canyon, where Tucker chose to build his own live-work dream house in 1984.

“Basically, the intent was to make something that was totally in agreement with the beautiful setting, which meant a partially subterranean house dug into the hillside and opening out to big panoramic views on both sides,” he said.

The site was so steep that Tucker enlisted MKM & Associates in Santa Rosa to draw up plans, which called for bolting the house into a cement block, itself bolted into the mountain with steel and concrete piers.

“There’s nothing more boring than a flat piece of dirt,” said Tucker, 83.

He designed a 1,750-square-foot house that served his and his wife’s needs, with nothing superfluous.

“Our budget was restricted and we didn’t have any kids. We could make it into an adult’s environment and kept it compact for that purpose,” he said.

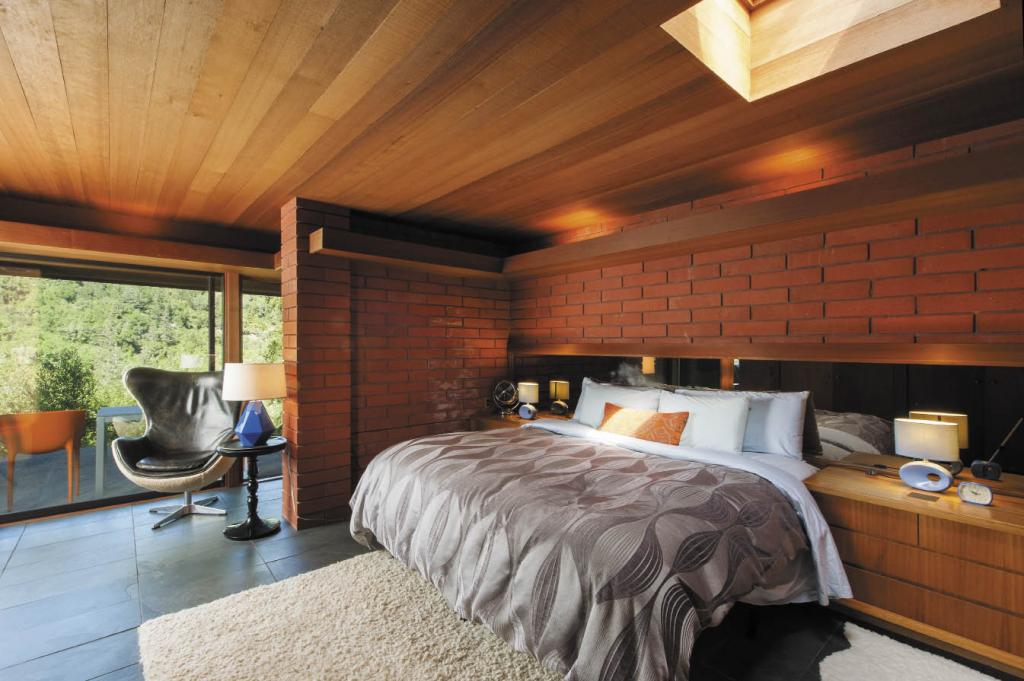

There is a cathedral-like quality to the design, with a central living room and kitchen under a 16-foot-high gabled roof with a rounded skylight along the spine. The two interior spaces are separated only by a formidable fireplace of red-brick blocks with ceramic brick facing. Two wings extend in either direction, like transepts from the nave of a church. On either side is a bedroom and bath, although one of the rooms served as Tucker’s work nook.

In keeping with Wright’s design principles, Tucker made use of different ceiling heights to create distinct spaces while keeping everything open. The bedroom and office ceilings drop to a cozy 8 feet.

Tucker continued to live and work at the Los Alamos Canyon house until age and a mild case of Parkinson’s disease made it too difficult for him to manage the steep slope and many steps. He moved to Oakmont and put his house on the market.

When Tudor-Jackson first saw the home, it seemed as if the forest had reclaimed it. Tucker had designed a living roof and planted ivy, but the vines had all but covered the structure. A long series of steps leads down to the front door from a parking terrace. Looking down from above, it appears like a hobbit house snuggled into the earth.

Tudor-Jackson and his spouse, Douglas Atkin, who works for Airbnb, were living in San Francisco and in the process of giving up a 200-year-old farmhouse and estate in upstate New York when Tudor-Jackson felt a pull back to the country.

It was a chance stay at an Occidental Airbnb cottage owned by Virginia Rago, a project planner and designer, that drew him to Sonoma. He returned to the cottage several times and the two became friends. At one point he told Rago, “I have to live in Sonoma County someday.”

“I went onto Zillow and for six months every morning I’d spend my coffee time looking all over California for just a cabin in the woods somewhere,” Tudor-Jackson said. “And then I saw how much property cost in California and I got really discouraged.”

In all that time, the only listing he bookmarked was an intriguing house in rural Santa Rosa. But when Tudor-Jackson called to inquire, it was already under contract for sale. He arranged to see it anyway, selling himself as a potential backup if the deal fell through. The day he met Gary Tucker at the house in December 2013 was the very day escrow closed on his 200-acre farm in New York, leaving him feeling both wistful and hopeful.

“When I was standing outside with Gary, I don’t know what it was, but we really connected,” Tudor-Jackson remembered. “Here he had designed and built it himself and lived in it for 30 years. I expressed to him how I understand what that means and that although it was already in contract, I reassured him — telling him it was going to be mine and that I’m going to take the best care of it in the world and love every corner of it.”

The next day the first offer fell through. The house was Tudor’s for $700,000. But until escrow closed on Jan. 31, 2014, he was “manically obsessed.”

“There wasn’t a day I wouldn’t look at a picture of the house and say, ‘You’re going to be mine,’” he said.

He immediately set to work restoring it, enlisting Rago to help. With a math degree from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, N.Y., she has a mind for engineering and construction challenges and even knew some of the contractors who had worked on other Gary Tucker homes.

“My heart is in the structure. I do furnishings, but that’s not my love,” Rago said. “My love is in the lines and making it work, making it flow. This is not a house you can show to just anyone and say, ‘Help us fix it.’ Most people don’t understand how it’s put together. But we were able to find the people who had worked on it.”

Tudor-Jackson’s work, nonetheless, has been mainly cosmetic, intended only to enhance what is already there. He cut back the overgrown ivy to reveal the striking geometry of the house. He replaced the ivy on the roof with a planting of wildflowers. Indoors, he applied beeswax, orange oil and a steam mop to bring out the beautiful grains of the woodwork. Rather than replace the studio tile, he meticulously brought it back to life with a wire brush. One of the few changes he made was to rip up the shag carpet and replace the concrete floor underneath with brick-shaped African black slate.

The furnishings, including an Eames coffee table and chair, also speak to the modern period. Tudor-Jackson’s pride and joy is his dining room set, a 1966 design by modernist Vladimir Kagan that was featured on “Star Trek.” He found it at a consignment shop in Marin and loves the fact that they were born in the same year.

His most recent project was a complete renovation of the swimming pool. It now has Mediterranean-blue plastering and is tiled with black slate that matches the redone flooring indoors.

Tudor-Jackson still makes his primary home in San Francisco and rents his “lair” on Airbnb when he’s not inhabiting it himself. He made Tucker’s desk into a daybed for guests, and the living room couch converts into a queen-size bed. It’s not the kind of house, he said, that is simply a spot to alight after flitting among restaurants and wineries. Mostly, whether he’s there alone with his two little hounds, Lady Margaret and Sir Oliver, or with friends, they all hunker down like summer camp. “We’re here. We dive into the pool and when we go out, we go hiking and then we come back and dive into the pool.”

Although there is more work ahead to preserve and restore Tucker’s dream home, Tudor-Jackson vows to never touch the architecture itself.

“I’m going to restore it like someone would clean a fine painting or revive a fresco,” he declared. “To me, it’s like a sacred art piece.”