In early October, a series of devastating fires ripped through Northern California. Now, with the fires at 100 percent containment, the region faces a new challenge: recovery.

For restaurant owners, who rely on Sonoma County’s tourism to sustain themselves and their employees, the fires threw things previously guaranteed–a steady stream of tourists during harvest season as well as a place to live–into upheaval.

We talked to Sonoma County restaurateurs who helped others as they grappled with uncertainty and their own personal losses during the fire, about their experiences and plans for the future.

Terri and Mark Stark

Willi’s Wine Bar was Mark and Terri Stark’s first restaurant. It was inspired by their second date, where they sat at the bar instead of a table, happily chatting with the staff and each other over a collection of smaller dishes. Their dream of opening a place like that was realized in 2002, when they had finally saved enough money to open Willi’s in an old Santa Rosa roadhouse. The Starks would eventually go on to open five more restaurants, but there was always something special about Willi’s. It was one of the first places to offer a now-popular selection of small plates, and more importantly, it had a distinctly local, comfortable feeling. You could enjoy a glass of local wine with friends, with no snobbery and no dress code. Dogs were welcome, as were small children.

Willi’s burned down in the early hours of Monday, October 9. That morning, Terri Stark was woken up by a call from their director of operations. She was fleeing from her home in the burning Coffey Park neighborhood and arrived at the Stark’s house with just her pajamas and purse. Soon, the Starks received another call. The manager who shut down Willi’s that night had heard about the fire, and raced back to turn off the restaurant’s gas. He then climbed on the roof to hose it down. He decided it was time to leave when he started noticing that the cars speeding down Old Redwood Highway were on fire.

The Starks didn’t know for certain if Willi’s had burned until around three in the morning, when local newspaper the Press Democrat posted a picture of the burning restaurant on their website. Their next days were spent in what Stark calls, “true survival mode,” as they hosted a house full of evacuated friends and were ready to evacuate themselves at any moment. On Thursday, they opened their other five restaurants (they had tried to open Wednesday, but the smoke was too thick.)

“It was really to get people back to work,” Terri Stark said of the decision to reopen. Her staff–the Starks employ over 400 people across their restaurants–was grappling with the same trauma and loss as everyone in the county, but as service industry workers, any time to the restaurant was closed meant a dip in their paycheck. “Our community needed a place to go again to have that meal or some semblance of normalcy,” she said. “I just felt like it was our duty to get the restaurants open as soon as possible.”

From Thursday to Sunday, the Starks provided free meals to evacuees and first responders at their remaining restaurants. Stark also started the daunting task of finding jobs for all 52 displaced Willi’s Wine Bar employees at their other restaurants. (As of our interview, she had succeeded.)

“The restaurants are our employees’ second home. And within each restaurant, they make up a family of their own,” she said. “For them to be around each other, it was really powerful and important.”

The Starks are still trying to find out if they can rebuild Willi’s–the historic nature of the property means it requires a host of improvements before it can operate as a commercial space–and in the meantime, they’re doing everything they can to ensure their guests have a great experience, so that Sonoma County remains a destination for tourists.

“Much of what Sonoma has to offer as far as wine country experience is still here and beautiful,” Stark said. “It would be even a bigger tragedy if businesses couldn’t survive in the aftermath of this and people lost their jobs. The trickle down from that is just going to add to the devastation.”

Dustin Valette

Dustin Valette grew up around airports. His mom flew for for REACH Air Medical Services, his dad for Cal Fire, so he’d end up waiting for them at the airport, washing planes and doing other chores. Sometimes during those trips, the airport would receive news of an airplane crash. Valette would be quickly shuffled away to his grandfather’s house, where he’d spend hours worrying, not knowing if the plane that had gone down had been carrying his parents, or one of their coworkers that had been over for dinner the previous Sunday.

Valette didn’t follow his parents’ path. He became a chef instead and opened Valette in Healdsburg in 2015. But his experiences growing up gave him an intimate knowledge of not just the uncertainty that comes with loving a first responder, but the logistics of their deployment. So when he was woken up early Monday by his young daughters, and started to hear about the fire’s horror from his friends, he knew that all firefighters would be deployed to fight it–except for one, who would required to stay back and cook for the rest of the team. What if, Valette thought, he did what he does best–cooking–so as many firefighters as possible could do what they do best?

That Monday, Valette went to his closed restaurant, took stock of what he had, and started cooking meals for the first responders like his dad, still a Cal Fire pilot. “Monday, those first responders had Kobe steaks, lobster and caviar, because that’s what we had in our walk-in,” Valette said. They made 150 meals that first day, and by the end of the week, with the help of friends, they were making about 400 dinners a night for the first responders, a pattern they continued for about a week and a half. At one point, a crew in Geyserville loaded up one of their trucks with the food, and brought it up to the middle of the fire so the crew could take a break.

The meals didn’t just provide sustenance but an injection of morale, Valette said. “When we showed up on Wednesday afternoon, they were eating government-issued peanut butter, and government-issued bread. So basically, hell,” he said. “To see them go from [a] piece of peanut butter and cold bread to eating roasted pork and braised chicken…[we gave] them a sense of something to look forward to at the end of the day, fuel that wasn’t just calories, but a sense of enjoyment.”

“The morale changed instantaneously. It was like…kids at Christmas,” he continued. “Everybody came running out of the tents, everyone’s clapping, and these are people who are risking their lives. Jumping out of helicopters into burn zones to put out a fire, with nothing but a rake. And here they are, coming right up like little kids clapping, because it was such a huge thing for them.”

The fires are now contained, but Valette still has plans to help the first responders. He’s working at Chefsgiving, a chef-driven fundraiser, and he’s also the chair of Rise Up Sonoma, a December fundraiser featuring food, wine and a silent auction.

And while his restaurant is safe, as is his home, he’s still recovering in other ways.

“We’re definitely nervous. I mean, in the first two weeks our restaurant lost $60,000. And that was just because we were putting a lot of money out for first responders, but also because the sales, the revenue, wasn’t there. And I think everybody, in the industry, is nervous,” he said. And It’s not just the obvious–hotels and restaurants–that will be affected by a drop in tourism, he added.

“Our cheese lady. Simple and funny as that is, our cheese lady, who we buy cheese from…We didn’t order cheese for a week, because we didn’t have people buying the cheese,” he said. “So, all of a sudden, she’s not selling the cheese, she has to cut back her staff, and then, the delivery driver who usually gets paid 100 bucks to go drive here and drop it off, well, they don’t need him, so he doesn’t need to work, so his hours [are] cut. It’s just a huge trickle-down effect.”

The Ochoa Family

On the night of Sunday, October 8, the Ochoa family, owners of popular downtown Santa Rosa taqueria El Patio #2, watched a movie together at their Fountaingrove home. The daughter, Maria Ochoa, fell asleep during the movie, and afterwards, when the rest of the family headed to bed, she wasn’t tired. So she stayed up, watching YouTube videos late into the night. As it grew later, she started noticing things. The people talking outside her window still hadn’t left. People were starting their cars. The smell of smoke her family had noted earlier still lingered.

“I couldn’t go to sleep,” she said. So she stepped outside. “Once I went out to see, I felt this heat wave.” That’s when she went back in and woke up her mom.

-

Maria Ochoa, daughter of the owner of El Patio in Santa Rosa. (Wendy Goodfriend)

The Ochoas decided to leave for another property they owned that they usually rent out, but was currently empty, They gathered their cats and dogs, but Maria’s mother was forced to leave her beloved pet birds behind as they fled. The next morning, her mother returned to the neighborhood for them, but the road was blocked off. A police officer took pity on her, and escorted her back to their house.

“She was the first one to notice that our house was gone,” Maria said. “She came back crying and she told us all that our house was gone.”

The Ochoas didn’t open El Patio on Monday or Tuesday. But on Wednesday, Maria and her father, Sergio Ochoa, El Patio’s owner, were back with their employees, making tacos and burritos for their customers as they adjusted to their new life. A friend of the family noticed their dedication, and posted about Sergio’s return to work on Facebook in a post that quickly amassed more than a hundred supportive comments.

“It was really amazing,” Maria Ochoa said, of the post. “I didn’t know people showed that much love for us, especially [for] my dad. I couldn’t believe it. I couldn’t stop smiling.”

As word spread, the Ochoas have been inundated with gifts of clothing and gift cards. The support surprised Sergio, who didn’t expect people to be thinking about him. It’s a role reversal for Sergio, who is usually the one helping others–in particular, the homeless people who occupy the park across from the restaurant, who Ochoa regularly feeds, passing out burritos to those who seem hungry. “I had a little change five years ago,” Ochoa said. All of a sudden, he started “worry[ing] about other people on the streets. And I started giving some meals, and I’m feeling good.”

Like a lot of people, the Ochoas aren’t sure if they’ll rebuild their home. They’re slowly returning to normalcy, one order at a time, adjusting to their new routines, new housing situations, and–for Sergio–the new feeling of someone worrying about him. “A lot of people are helping people right now. I am so surprised…[it’s] very nice.”

Erik Johnson

Marissa Alden was in China on a business trip when she found out about the fires. A neighbor sent her a message: the fires were getting closer. Was her family evacuating? Frantic, she called her husband, Erik Johnson. He didn’t get the message, thanks to their Cloverdale home’s spotty cell reception. She finally got through to his parents, who were staying with Johnson to help out with childcare while she was away. After being woken up by his stepdad, Johnson sprung out of bed, and gathered their twin daughters, explaining to them as calmly as he could manage that there was a fire, and they needed to leave immediately. The family evacuated to his mom’s house in downtown Cloverdale, where they remained for the next few days.

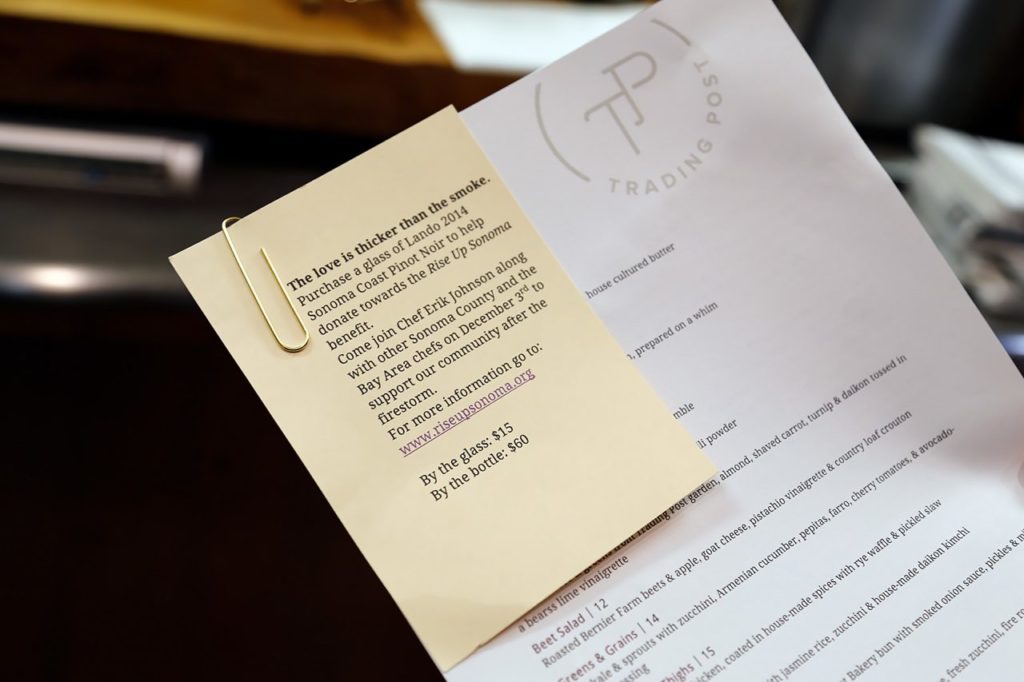

Alden and Johnson own the Trading Post in Cloverdale, and that Monday, Johnson started cooking. The Pocket Fire that affected Cloverdale didn’t cause as much damage as the Tubbs fire in Santa Rosa, so evacuees turned away from the overfilled Santa Rosa shelters soon headed north to Cloverdale to find refuge. For two days, Johnson prepared meals for evacuees staying at the Citrus Fairgrounds evacuation shelter, down the street from the Trading Post.

People quickly joined in. The baker at his restaurant contributed some loaves of focaccia to go with the lasagna he made. His neighbor, a farmer who provides much of the produce for his restaurant, donated greens he turned into a salad. A local market donated some dairy and dry goods.

“We just wanted to cook some home-cooked, sort of comfort food for folks down there. Just to give them a warm meal that hopefully they would enjoy,” he said. “The first instinct that I had was how can I help, what can I do to help? And the obvious way to help was I have a commercial kitchen, and [I could] rally some people in the community around to help donate a little bit of food. It just felt good to do that.”

Johnson and his family were able to return home on Wednesday, but were then forced to evacuate again after the winds shifted. His house was ultimately fine, and he reopened his restaurant on Thursday. “We opened back up because we just knew that there’s a lot of people in town that kind of want normalcy, and wanted to be able to gather somewhere and eat,” he said.

Johnson is participating in the Rise Up Sonoma event with Valette in December, and like Valette, he’s anxiously waiting to see what the long-term economic effects will happen as a result of the fire.

“I wouldn’t say it’s dire, but it’s a little bit slower than usual,” he said. He wants people to know that, “Sonoma County didn’t burn to a crisp, it’s still here. It’s beautiful.”

This story was originally published on kqed.org/bayareabites.