Threats to life. Debilitating fear. Feelings of utter chaos and complete helplessness.

These were some of the emotions North Bay residents experienced during last October’s firestorm. These very same emotions also comprise the American Psychiatric Association’s definition for PTSD, or Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.

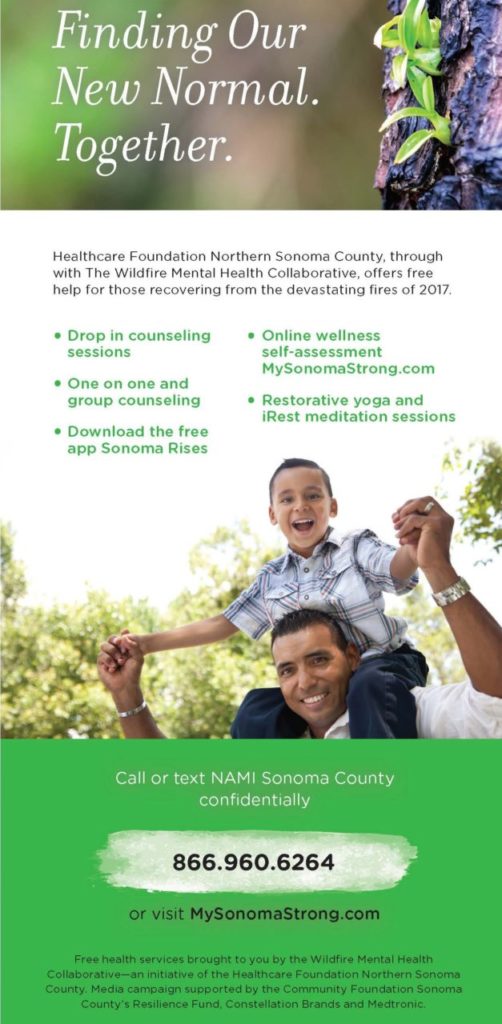

To help fire survivors work through the complex set of emotions that invariably follow large scale disasters, a group of Sonoma County mental health professionals have banded together to form the Wildfire Mental Health Collaborative (WMHC).

The group aims to provide mental health services to survivors while at the same time studying what kinds of treatments work best in addressing the lasting effects of trauma. Ultimately, according to Debbie Mason, CEO of the Healthcare Foundation of Northern Sonoma County, data from this initiative could revolutionize the way communities and mental health providers respond to the lingering effects of natural disasters.

“If people don’t take care of their mental health, nothing else really matters,” she says. “Part of being ‘strong’ at a time like this is being strong enough to ask for help. The whole point of this initiative is to come together in a loving embrace to support each other in our healing.”

Mason’s organization is spearheading the initiative, along with participants from the National Association for Mental Illness Sonoma County, the Redwood Psychological Association, the Redwood Empire chapter of the California Association of Marriage and Family Therapists and independent psychologists and researchers. To date, the $1.3-million initiative comprises a variety of programs, each designed to address a different—and important—aspect of mental health.

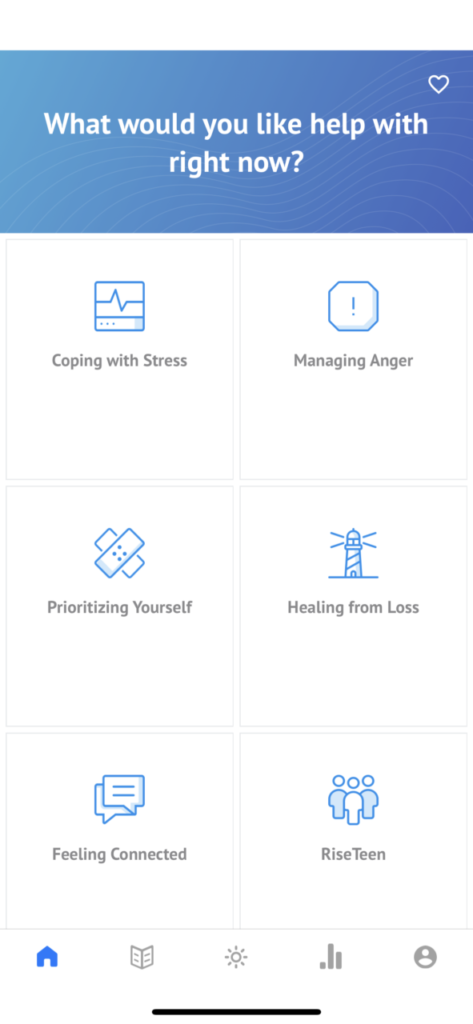

The newest of these programs, Sonoma Rises, is an English-language app for fire survivors which debuted earlier this month. The app helps connect survivors with services across the region, and provides customized, evidence-informed tools to help cope with stress, heal from loss, prioritize self-care, connect with others, manage anger, and track moods using validated assessments over time. The app includes a special section geared for teens; a Spanish-language version is expected soon.

Dr. Adrienne Heinz, a clinical and research psychologist at the VA National Center for PTSD helped develop the app.

“We felt like an app was the perfect medium because people are on their phones all the time anyway,” Dr. Heinz explains. “Someone might have a stigma about going to see a therapist, but the same person wouldn’t think twice about interacting with doctors and other experts through an app.”

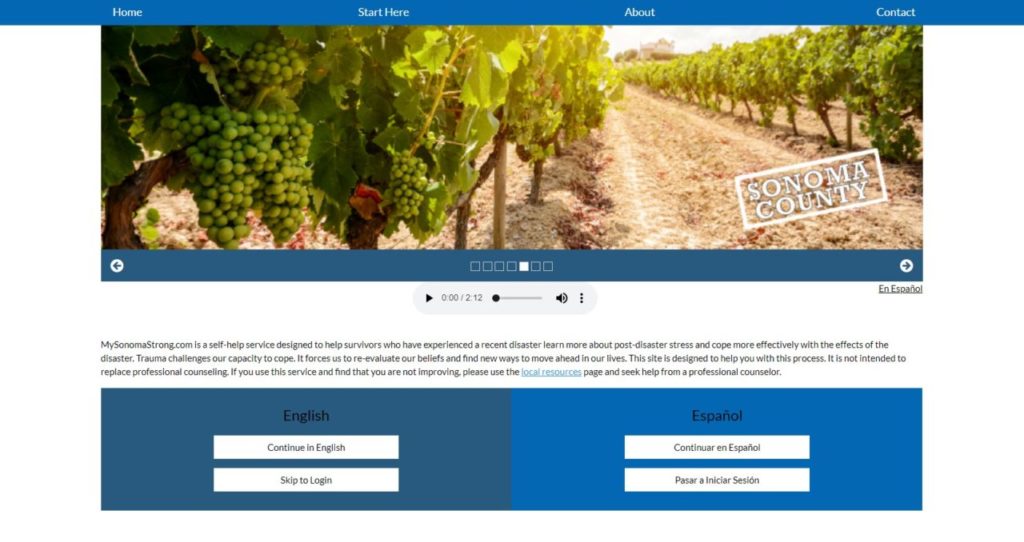

Another technology-oriented effort is the bilingual website mysonomastrong.com. The site provides resources for self-care and for finding free professional therapy in Sonoma County. It also offers tools for users to track moods, and it provides interactive suggestions for relaxing in moments of heightened stress.

In the eight weeks before launch (and with no promotion), the site attracted nearly 1,700 visitors. After a regional ad campaign began on the one-year anniversary of the fires, those numbers have increased exponentially.

Other WMHC initiatives have focused on different aspects of wellness.

In the area of mental health, WMHC affiliates have worked with the FEMA-supported California HOPE Program to set up two groups of fire survivors for ongoing (and free) weekly group counseling.

WMHC team members have also run workshops and webinars to train more than 300 mental health professionals in Skills for Psychological Recovery (SPR), a modular intervention therapy specifically designed to help survivors gain skills to manage distress and cope with post-disaster adversity.

Dr. Josef Ruzek, co-director of the Center for M Squared Health at Palo Alto University and an adjunct professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at Stanford University, was part of the team that helped create the SPR protocols. He notes that these trainings are based on an understanding that disaster survivors will experience a broad range of reactions over differing periods of time.

“We want [therapists] to put patients in the best position to get through all of this,” says Dr. Ruzek.

Once providers complete the training, the WMHC encourages them to offer fire victim clients up to five therapy sessions for free. Dr. Christine Naber, a neuropsychologist in the Neurology department at Kaiser Santa Rosa and president of the Redwood Psychological Association, adds that a critical part of the SPR training is preparing therapists to offer clients “booster” sessions that correlate to milestone anniversaries or other potential triggers.

“Generally short-term treatment is effective, but when there’s trauma involved, people might need a longer-term approach,” says Dr. Naber. “That’s what makes an initiative like this so important.”

The WMHC initiative also addresses physical wellness through yoga. The program currently sponsors a dozen free yoga classes across Sonoma County, and has trained more than 60 yoga instructors in a special type of yoga designed to help people experiencing PTSD.

David Leal, a certified yoga instructor, lost his Coffey Park home in the Tubbs Fire. After the fire, he received “trauma-informed” yoga training through the WMHC initiative and describes this version of yoga as particularly meditative.

Leal says that by slowing everything down, participants are forced to relax their bodies and minds. There’s deep breathing. There’s self-massage. There’s lots of time to think.

“Anything that’s going to calm the breath cycle so that the body’s parasympathetic nervous system can kick back in and relax and release the tension,” says Leal. “People don’t realize how important that is.”

The WMHC group’s goal is to train a total of 500 mental health professionals in SPR; there are a number of workshops left to teach. Yoga training will continue through the winter as well; WMHC officials would like to train 100 yoga instructors by early next year.

Long term, WMHC leadership hopes their efforts will help to establish new data on how people grapple with mental health in the wake of natural disasters. Central to this effort will be reports that patients administer themselves—they’ll answer brief questionnaires about their well-being before and after each session.

Researchers from Stanford and other institutions will then review the responses for possible future application of the data in the field. Eventually, this data could be used to respond to natural disasters in other cities all over the world.

Mason, from the Healthcare Foundation, says she and her colleagues will judge the success of the initiative by how many people it helps. At the same time, she adds, the potential for an even larger impact is undeniable.

“Between the connectivity, peer-to-peer teaching, and networking we’ve seen with this effort, the possibilities for what we can learn and how we can change our responses to natural disasters are pretty incredible,” she says. “We did this to take care of our little community. In the process, we just might end up changing the national conversation about the best way to approach post-disaster mental health.”

The WMHC initiative is aimed for anyone who feels that they need help and coping skills since the fires. Sonoma County residents who are looking for wildfire mental health support services, such as individual or group counseling, trauma-informed yoga, or other support services, may visit mysonomastrong.com; or call or text NAMI (confidentially) at 1-866-960-6264.

To support these services, please contact the Healthcare Foundation at (707) 473-0583 or info@healthcarefoundation.net.