As Jonathan Lee rounded a redwood-shrouded curve on Old River Road near Forestville, he saw a sight that chills any cyclist’s blood: an older-model sedan approaching on the wrong side of the road, headed straight for his handlebars.

“I remember hitting the brakes, but I wasn’t trying to swerve or anything. It was going to happen,” he said. “There was no out. I instantly went, ‘This is going to be bad.’”

“I remember hitting the brakes, but I wasn’t trying to swerve or anything. It was going to happen,” he said. “There was no out. I instantly went, ‘This is going to be bad.’”

The impact bounced Lee, 41, off the windshield and straight into the air, spinning like the blades of a helicopter. He landed flat on his back, unconscious but alive. He survived without broken bones, but he suffered a severe concussion that sidelined him for weeks.

Lee, an avid competitive cyclist from Santa Rosa, said he is grateful for not remembering the impact, which easily could have killed him. He does, however, remember that awful final moment before the blow.

“Honestly, I remember thinking this is death, this is the end,” he said, six months after that perilous encounter in September 2013.

Lee is one of dozens of cyclists injured on the county’s roads last year as Sonoma has exploded in popularity and acquired a worldwide reputation as a cycling destination.

“You’ve got valleys, you’ve got the redwoods, you’ve got the vineyards, you’ve got the ocean all within an easy one day’s training,” said Santa Rosa

cyclist Bob Grove, explaining the draw.

As the number of cyclists grows, so does the tension on scenic back roads, charming because they are narrow and twisting. Often, danger waits around the blind corners on roads simply not wide enough to accommodate both drivers and riders, who range from cycling pros to tourists renting bikes for the day. Encounters sometimes leave motorists and cyclists baffled and more than a little frustrated. Although there is plenty of blame to go around, cyclists themselves admit that sometimes their own behavior contributes to the unease, when bikers fail to stop at lights and stop signs, ride in lane-blocking packs, or pedal down the wrong side of the road.

“I think what happens is a lot of times, motorists get angry at bikers when they act like boneheads,” said Jim Keene, co-owner of Santa Rosa’s NorCal

Bike Sport shop.

The influx of cyclists to Sonoma County started with the pros, who found that the steep climbs of west county roads simulated the grueling mountain

stages of the Tour de France and other iconic races, but with weather conditions that allow year-round training. It moved on to serious cyclists, who flocked to the annual GrandFondo ride established in 2009 by international cycling star Levi Leipheimer. He moved to Santa Rosa and has extolled the virtues of the county’s rugged rural rides such as King Ridge Road, along the steep hills above Cazadero in northwest Sonoma County.

The attraction has now filtered down to the more casual riders, commuters and recreational cyclists who populate the roads in ever-greater numbers.

And it’s easy to see why: sweeping views across the rugged coast from Coleman Valley Road near Bodega Bay; cool, moist redwood forests on Bohemian Highway and River Road near Occidental and Guerneville; rolling vineyards along Healdsburg’s Westside Road and West Dry Creek Road, the fields covered with mustard in the spring and grapes in the summer; roads dotted with wineries, all under the looming bulk of Mount St. Helena on the horizon.

“Look around you. What’s not to like?” asked bride-to-be Karen Runde of Burlingame, who was pedaling a rented bike along West Dry Creek Road with some girlfriends for a bachelorette weekend recently.

“Just these rolling hills, you feel like you’re in ‘The Sound of Music.’ It’s very peaceful. The homes are gorgeous. There’s a lot of character and charm.”

Yet the reality is that Sonoma County’s local road network is, in many places, little more than a patchwork of glorified farm trails, the paved-over remnants of horse cart tracks through the wilderness that were never reengineered to meet the needs of the 20th century, much less the 21st. The sprawling road system is beyond the financial ability of the county to maintain, leaving many of the rural roads in poor condition, as much patch as pavement, even as the population increases (half a million residents and growing), putting even more vehicles on those roads.

The multiplying crowds of cyclists leave the person in charge of maintaining those roads scratching his head.

“I am just amazed that people ride on narrow country roads where the speed limit is 45 or 50 miles per hour,” said Tom O’Kane, deputy director of the county’s Transportation and Public Works Department. “I think that is just a deathtrap. Then they expect motorists to look out for them.”

That growing competition for space has led to a number of high-profile injuries and deaths in recent years, including a 2012 hit-and-run collision in Alexander Valley that left internationally known competitive cyclist Michael Torckler of New Zealand bleeding and broken beside Pine Flat Road, a route widely known as challenging even for pro-level riders.

The accident nearly ended his cycling career. Driver Arthur Yu of Rohnert Park was sentenced to 10 years in prison for hit-and-run and reckless driving.

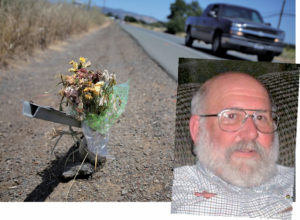

That same year, beloved Sonoma State University professor Steve Norwick, 68, died after being struck from behind by a vehicle on Petaluma Hill Road. That roadway is wide and relatively well-maintained, but cyclists say a combination of heavy commuter traffic, high vehicle speeds and debris accumulated on the shoulders can make it a hair-raising ride.

Sometimes, though not often, the tussle over asphalt degenerates into violence. Perhaps most famously, Santa Rosa motorist Harry E. Smith struck cyclist Toraj Soltani after a confrontation on Pythian Road southeast of Santa Rosa. When Soltani tried to flee, Smith drove off the road after him, chasing him onto the Oakmont golf course, bumping his rear tire.

That threw Soltani from his bike, causing severe wrist injuries. Smith later pleaded guilty to two counts of assault with a deadly weapon and other charges, but was sentenced to five years in a medical center after a doctor testified the then-82-year-old man was suffering from dementia at the time of the attack.

“Sadly, we have had a number of troubling incidents, but that does tend to reinforce the idea that it isn’t safe to ride,” said west county Supervisor Efren Carrillo, who has been an enthusiastic promoter of cycle-based tourism. “Some of these tragedies tend to promote finger pointing … unfortunately, it is divisive and counterproductive, and I do think it is a misrepresentation of reality.”

Penngrove resident Dianne Magliulo is acutely conscious of those sorts of events when she rides the county’s roads with her husband, Wayne, particularly such busy thoroughfares as Old Redwood Highway near her home.

“I don’t like the speed of the cars going by me and the trucks,” she said, taking a break during a recent back-country ride. “It makes me a little bit too stressed to be comfortable driving on those roads, even though they’re accommodating people.”

Although the back roads seem narrower and more threatening to drivers, Magliulo said, from a biker’s point of view, routes like West Dry Creek Road, where the Magliulos were riding that day, are better.

“It’s winding and people are paying more attention,” on the back roads, she said. “But you go down Old Redwood Highway, Petaluma Hill Road, and, I mean, are just barreling down there, 60 miles an hour.”

But, Magliulo admitted, she thinks carefully before she and her husband decide to pull into one of the area’s many wineries, hoping “Nobody will be behind us in a car after going to six of them,” she said.

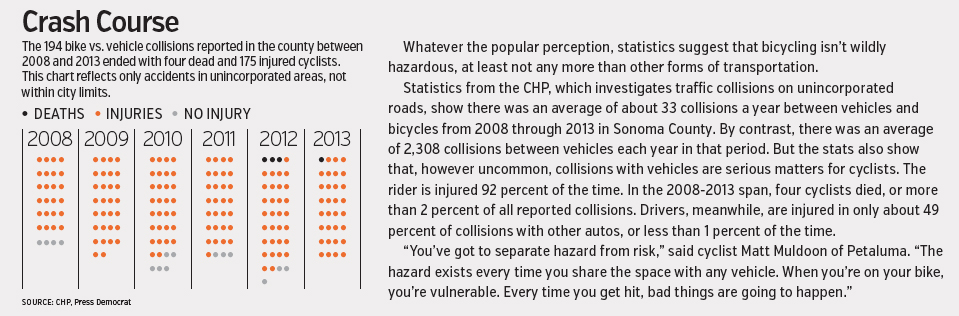

There are an average of 33 collisions a year involving bikes and motor vehicles on county roads, according to the CHP, which does not track accidents on city streets. Deaths, while sensational, are mercifully rare: four cyclists have died on county roads since 2008, three of them in 2012.

But those relatively modest numbers belie the stress on the roadways. Few topics generate as much emotion among riders and motorists alike.

Drivers tend to decry the arrogant, traffic-blocking, law-flouting ways of the cyclists. They travel in packs that block the lanes. They refuse to move to the right to allow traffic to pass. They blow through stop signs and zip around downhill turns in the wrong lane.

“They have been pretty obnoxious riding on some of the narrow roads,” O’Kane said of his on-the-road encounters with cyclists. “I get the Bronx salute or the raspberry salute and I’m on my side of the road and they’re in a group. … I don’t forget things like that.”

For their part, cyclists complain bitterly about clueless or overtly hostile drivers failing to share the road, endangering their lives.

“I have definitely noticed an increase … in really negative emotions from motorists,” said Lauren Lee, wife of Jonathan Lee and a board member of the Red Peloton, a Santa Rosa-based cycling club. “It takes the form of flipping us off, honking at us, getting buzzed.”

Even more alarming, cyclists say, are the motorists who are playing with the radio, using their phone, or simply being unaware of their surroundings.

“We’ve got to get serious about distracted driving because that’s where you get your best return on investment,” said Supervisor Shirlee Zane, herself an active cyclist and the backer of several initiatives to protect pedestrians and bike riders from collisions with motor vehicles.

The growing number of cyclists has caused conflicts between riders and residents of these rural routes, who have been used to having the roads to themselves for decades. In 2010, the swell of cyclists led to a series of emotional meetings in Cazadero, with residents complaining vehemently about being overrun by bikes. They accused officials of caving in to cyclist pressure when the county removed two cattle guards, which kept free-range cattle from wandering off, yet posed a hazard to elite riders who liked to train in the area.

Into the breach stepped longtime resident Charlotte Berry, owner of Cazadero Hardware. She negotiated a truce between residents and cyclists

Into the breach stepped longtime resident Charlotte Berry, owner of Cazadero Hardware. She negotiated a truce between residents and cyclists

that has held the peace to this day.

“Hey, it’s just bicyclists. They have the right to be on the roads, too,” she said, though she admitted that as a motorist, “I understand how scary it is.

Your heart jumps out of your chest when you see a bicyclist.”

She and others say the growing friction between cyclists and motorists is just a stage to a better future, a day when road users are more used to one another.

“It’s the growing pains of trying to make Sonoma County a special place, to make Sonoma County even more bike-friendly,” Berry said.

Yet the squeeze on road space continues on the winery-studded rural lanes west of Healdsburg.

West Dry Creek Road resident Fred Corson has seen the ranks of cyclists swell since he moved to the area in 1998, coinciding with the boom in wineries and the resulting uptick in traffic.

“I think we’re lucky we haven’t had more serious problems,” he said. “I think it is only a matter of time.”

West Dry Creek Road is a nationally known route for cyclists and wine tasters alike, winding through some of the most scenic parts of Wine County. From Corson’s neighbodhood, wineries can be seen for miles, as far as the Mayacamas Mountains on the edge of Lake County. But the road is so narrow that two motor vehicles barely fit side by side. On the west side of the road, hills and fences mark off the homes and farms. On the east, the raised pavement drops off to ditches and fields.

Corson said he has seen a surge in cyclists, going from a trickle to a constant stream on busy weekends.

The presence of large group rides and events makes it slow and difficult to get in and out of the neighborhood.

Corson is not opposed to cyclists, explaining that tourists provide the money that keeps the region rural, yet he still worries about the potential for a

serious accident on the cramped roadway.

“I have a real problem with novice bicyclists, the ones that are the most dangerous,” he said. “They don’t know what to do, they are the most unstable, they fall over in front of you.”

At least some of those less-experienced riders come by way of the booming business in bike rentals and guided tours. Bike shop owners in Healdsburg said they have seen their business soar in recent years. They also said they are making an effort to get their rental customers to follow the rules of the road, respect motorists, and be conscious of the residents of the area.

“We kind of feel like when someone comes to us, we have the chance to give them information on how to make it safer for everyone — ride single

file, respect other users, obey traffic laws,” said John Mastrianni, owner of Wine Country Bikes, which rents more than 8,000 bikes every year. He added, “We caution them a great deal about drinking and biking.”

Richard Peacock, owner of Spoke Folks, which also rents bikes, said he tries to steer customers away from routes that seem beyond their abilities or which might expose them to high-speed traffic, though he acknowledges that customers are free to ignore his suggestions.

“What we say is, ‘Here are the quieter roads,’” he said. “Quieter roads are what you want.”

Tourists are often surprised that Sonoma County has few dedicated bike trails and that the most scenic rides require pedaling on the open road.

“Sometimes they’ll decline to ride because they feel uncomfortable riding on the road with cars,” Peacock said, “but that is really rare.”

Bicyclists remain a small but important customer base for the wineries that line routes such as Westside Road, said Alex Davis, whose family has

owned Porter Creek Vineyards for 35 years. About 10 percent of the customer traffic on busy days comes in on two wheels.

“In the old days, wineries used to discourage bicyclists since they would come in to taste but not buy anything,” he said. With the increasing ease of

interstate wine shipping, however, cyclists are more willing to spend their money at wineries.

Some producers actively court bicycle traffic now.

The 2-year-old tasting room at Martorana Family Winery on West Dry Creek Road advertises its bike-friendly nature by mounting the front wheel of a bike on its sign. Hospitality Manager Wendy Cox said at least 20 cyclists come in every day on a busy weekend, at least 10 percent of the total. Most visitors report safe and enjoyable rides along the rural roads, she said.

As a motorist on the way to and from work, Cox has simply learned to be tolerant, even in cases when cyclists forget themselves and ride two or three

abreast, making it difficult for cars to get by even on the best parts of the road.

“I’ve learned to be patient in my old age,” she said. “It’s not really that important to get there at a particular time.”

Although the roads are crowded, cyclists say the notion that their sport is any more dangerous than other activities is overblown.

“People who haven’t ridden are very afraid to go out on the road and it’s because of the perception of safety,” said Gary Helfrich, executive director of the Sonoma County Bicycle Coalition, an advocacy group for bike and pedestrian safety. “When something can change your life in an instant, like getting hit by a car, we’re very, very afraid of it. When it can ruin your life incrementally, like not getting exercise, we don’t think about it.”

But Jonathan Lee is not so sure about the distinction between perception and reality. As it turns out, that near-fatal encounter on Old River Road in September 2013 was his second major crash in about 30 days.

Lee and a group of friends had been zipping downhill on Occidental Road in August when they came around a turn and encountered a car that had just backed out of a driveway into their lane. There was plenty of room to pull left and save himself, Lee said, but then the unbelievable happened: the car turned back into the driveway, pulling left into the path of the oncoming cyclists.

Lee, in the lead of the pack as was his habit, slammed straight into the side of the car, traveling 40 mph. The impact vaulted him off the bike and sent him skidding along a gravel driveway.

“The hand of God was there and I was banged up pretty good, but miraculously the bike was totally unbroken, and I actually rode home,” Lee said. “The helmet was gone and I was torn up.”

That first crash caused occasional panicked flashbacks, but did not shake his devotion to competitive cycling. In fact, Lee dusted himself off and rode in a race the next day.

But the second crash was too much. Lee and his wife have dramatically scaled back the number and length of their rides. He’s inclined to give up road riding and stick to off-road trails, where cars will no longer trouble him.

“I think,” Lee said, contemplating the ever-crowded public roads, “it is a ticking time bomb.”