A few hours past dawn in the Santa Rosa Rural Cemetery, John Dennison stood beneath a cluster of oak trees with the rest of the Tombstone Trio — fellow retirees Scott Minnis and Henry Katz — as they surveyed the site of their latest graveyard excavation.

“You can hardly describe what it feels like when you go in there and hit something solid,” Dennison said. “Then you start digging like a little gopher.”

Almost glum and dank with dew, the scattered grave markers seemed ill prepared for a radiant sunny morning after decades of hibernation beneath brush and dirt.

Several weeks before, a distant relative of May Sumner, who was buried in 1912, contacted cemetery archivist Sandy Frary through the website findagrave.com, looking for Sumner’s marker. Frary checked the grave registry and map of 5,250 plots and told the trio to look in the overgrown outer edge of Stanley Cemetery, one of several adjoining graveyards, along with Moke and Fulkerson, which make up the 17-acre Santa Rosa Rural Cemetery — just a short block from McDonald Avenue, Santa Rosa’s stateliest street.

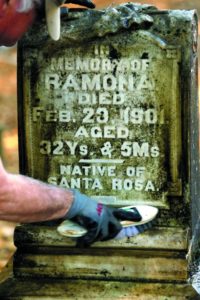

Hitting pay dirt, the men unearthed four graves buried beneath several feet of ivy, bramble and soil. “And here is May Sumner,” said Dennison as he leaned down to wipe off her faded headstone, the engraved letters barely visible.

“Finding graves is about as exciting as this place gets,” Minnis added. “It’s like detective work.”

Over the past several decades, a small army of volunteers has transformed the once-neglected, city-owned cemetery from an overgrown vandal’s playground littered with trash and the occasional marijuana plot, to a sanctuary where neighbors walk and run their dogs and volunteers and thespians hold candlelit tours and period re-enactments.

There’s been no shortage of drama since the cemetery welcomed its first body in 1854. Back then, it was an old cow pasture handed down through Mexican land grants, before Missouri settler Thompson Mize “got drunk and drowned in a puddle,” Dennison said. Other versions call it a pond or a creek, but either way, Mize left behind a family of four to fend for themselves.

Others soon followed suit: The granddaughter of frontiersman Daniel Boone, Jack London’s cook, a popular black barber who ran a way station for freed slaves before the Civil War, still life painter Edward Edmondson and a rifle-twirling vaudeville performer whose body was left behind by her French troupe.

Countless veterans spanning the War of 1812, the Civil War, World War II and the Vietnam War, are buried here. Civil War hero Thomas Morton Goodman, the lone survivor of the Centralia (Missouri) Massacre of 1864, rests here.

There’s also former Santa Rosa mayor, judge and attorney Thomas Rutledge, who once defended the notorious Younger brothers outlaws of Missouri. Hundreds turned out when Santa Rosa’s first female physician, Annabel McGaughey Stuart, “Dr. Dear,” died in 1914. Members of the Grace family that once owned Grace Brothers Brewery are laid to rest beneath a recently vandalized monument (since carefully restored by the Tombstone Trio). And a mass grave from the 1906 earthquake includes several Press Democrat news carriers caught in the mayhem.

Making national news, the cemetery was the site of a famous lynching in 1920. After three hoodlums killed the local sheri and a detective, a mob busted them out of the Santa Rosa jail and hung the trio from the branch of a black locust tree.

Frary is compiling all this priceless history in one massive tome, with the help of co-writer Ray Owen, to be titled “Santa Rosa Rural Cemetery: Burial Listings.” There’s a chance it may be published later this year, but “more realistically” in 2017, she said.

“It’s basically a database, but you can sit down and read it like a book,” said Frary, now retired after more than 25 years as payroll clerk in the Sonoma County sheri’s oce. “It’s going to have all the stories. All of Santa Rosa is going to finally know who is buried here.”

It turns out that Frary’s grandfather was also buried in the rural cemetery. But like more than a thousand other gravesites, she still can’t find his marker, which was likely covered or lost over the years.

“I’ve tried everything,” she said. “I have his inquest, his death certificate, all the stu in the newspaper, but they never say exactly where.”

Her book will also include a few of the lingering ghost stories, including that of Sarah “Neva” Duffin, whose husband apparently tried to kill her, before she died in 1909 of kidney failure.

“It’s been said that she’s tapped people on the shoulder while they’re standing there (in the cemetery),” Frary said.

Former newspaperman Alan Lemmon, who died in 1919, likes to haunt those who come too close to his grave. “One of our volunteers has a photo of her grandson standing by his grave and you can see some kind of ghostlike presence in the photograph,” Frary explained.

She also gathered more than 1,000 wax rubbings of every epitaph in the cemetery for a previous book, “Tombstones and Tales Vol. III: Epitaphs.”

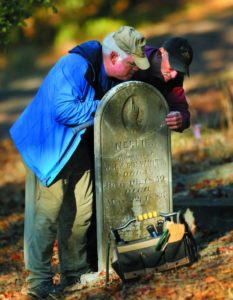

Meanwhile, every Tuesday and Thursday, the Tombstone Trio gathers around 9 a.m. to piece together the puzzle of broken headstones, clean up graffiti and vandalism, and mow under weeds and brush.

At 76, Dennison, a former furniture warehouse manager, is the soft-spoken leader. Minnis, 53, is the designated truck driver and hauler, and also the relative hipster in an Eagles concert T-shirt wrapped in flannel. And the more reserved Katz, 63, has a knack for mixing epoxy, cement and mortar.

Together, they wear the same tattered Santa Rosa Rural Cemetery baseball hats, bearing the logo on the back: “Where History Comes to Life.”

After more than five years working the graveyard beat, Minnis knows how he’s going out when the time comes: “It’s definitely reinforced my notion that I’m going to be cremated,” he said. “I don’t want to give vandals something to tag.”

Said Dennison: “I’m gonna be cremated. I just can’t bring myself to be put in the ground.”