Sonoma-based artist Kathryn Clark surveys a wall of her studio where a hand-stitched assemblage of pale-gray fabric swatches is affixed to a board with pearl-headed push pins. “Homage to Democracy,” as the work is called, is splashed in the light, and Clark, a self-described activist, is contemplating her next move.

The piece will become a 7×7-foot translucent tapestry representing both a map of Washington, D.C., and what Clark sees as the disintegration of government by the people, one cotton-organdy city block at a time. Clark arms herself with densely detailed city plans tattooed with colorful legends, bolts of cloth from one of San Francisco’s few remaining fabric stores, and a list of heady books that illuminate the smoldering social and political fires of the 21st century — predatory lending, demagoguery, money laundering, war-time refugees. From these sources, she produces large-format fabric works that express with quiet urgency the corrosive effects of the world’s most insidious threats, both visible and clandestine.

“There is this chipping away at our Constitution that happens daily now,” she says, gesturing toward what is the first in a series of quilt works that will include cities like Kyiv, Caracas, Hong Kong, Budapest, and London. “I offer a geopolitical perspective on politics through maps of cities where democracy is flailing.”

Clark moved to the town of Sonoma full time in July 2019 with her family after first purchasing her house, just a 15-minute walk from the Plaza, in 2011 as a getaway from San Francisco. “I love Sonoma all year, but fall and winter are really why I love it here,” she says. “The weekend crowds have mostly disappeared, the Plaza lighting ceremony kicks off the holiday season, and the restaurants shift their menus to reflect what’s growing around us.”

Born in Knoxville, Tennessee, and raised in Tallahassee, Florida, Clark is the product of a Bauhaus marriage: her father was an architect, her mother a textile artist who died of leukemia when Clark was only 17. She studied art and architecture and ultimately found her way to urban planning, where she worked under New Urbanism visionary Peter Calthorpe.

While her interest in architecture followed her father’s career, she did not associate her textile talent with her mother until she married, had a child, and began experimenting with painting and photography as a stay-at-home mom. “I remembered my mom’s huge loom,” she says. “And then I had an epiphany: No wonder I wanted to work in textiles.”

In 2011, as she was turning 40, the artist stumbled upon her calling, creating large-scale works that bring light to issues of social justice. “The goal of my work is to provoke a conversation,” she says. “But I’m an introvert, so this is my way of speaking out.”

Clark synthesizes the information she gathers from books, articles, podcasts, and Instagram feeds for months or even years before beginning to execute, vetting ideas and designs with organized peer reviews.

Public institutions, not private collections, are where she strives to have her work shown.

Her “Washington, D.C. Foreclosure Quilt,” was purchased by the Smithsonian’s Renwick Gallery. The quilt-and-embroidery piece, rendered in linen, cotton, and recycled thread, documents the effects of the 2007 recession and the economic distress of the subprime mortgage crisis that lingered long after disappearing from the headlines. Comparable maps for Detroit, Cleveland, Miami, Las Vegas, Albuquerque, and other municipalities followed.

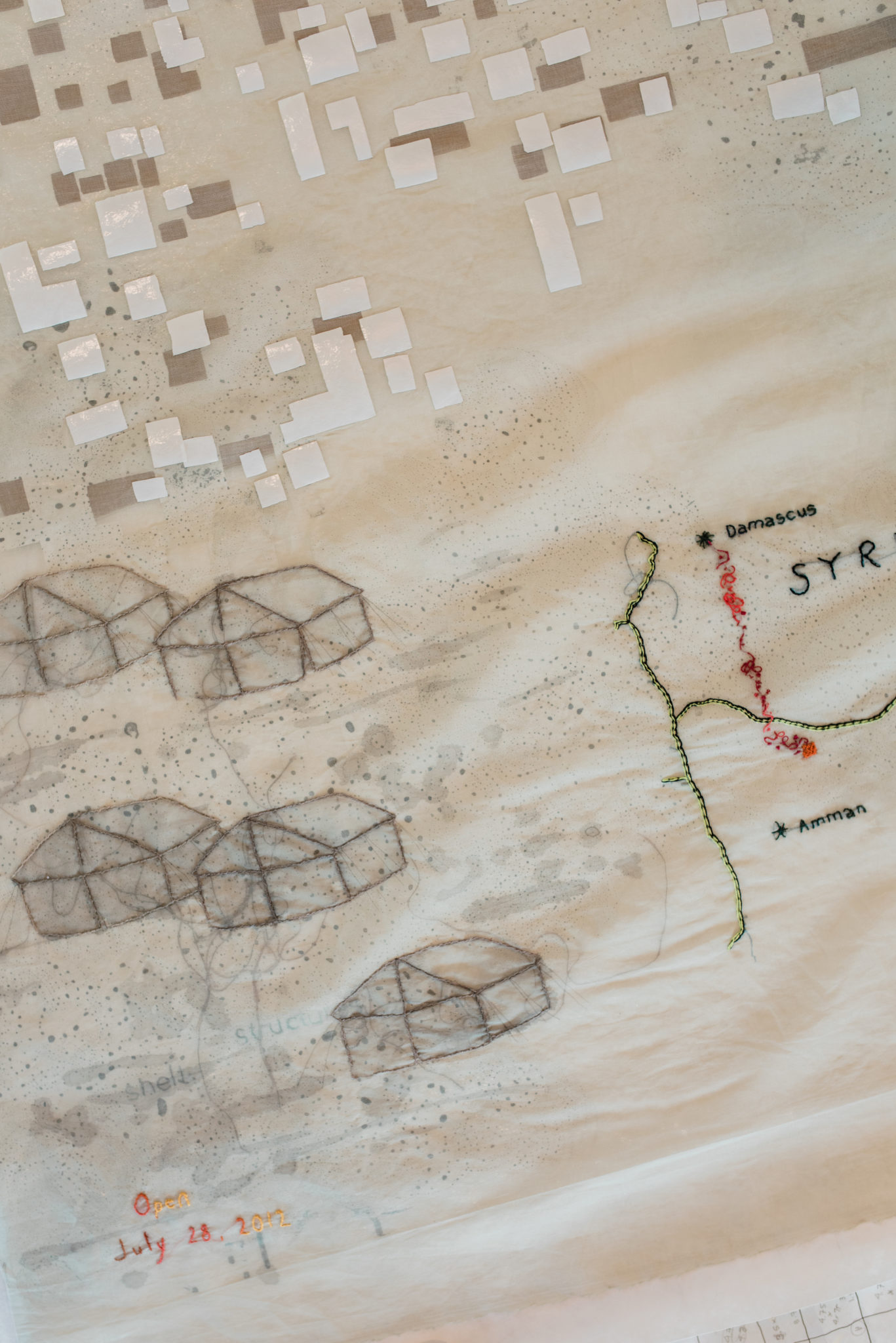

In 2018 she completed “Paul Manafort Money Laundering Blanket,” which depicts the glittering zig-zagging of transcontinental bling from the U.S. to Belgium, Ukraine, Russia, Cyprus, and the Grenadines, in hand-embroidery and beading on cotton organdy and gold silk. Her “Refugee Stories,” shown at the Riverside Art Museum in Riverside, California, uses embroidered panels to illustrate the path of Syrian refugees into Western Europe.

Clark, her husband, Dave, and their daughter had lived in San Francisco’s West Portal neighborhood for 13 years before they bought the home in Sonoma. In the house, she discovered an original hand-colored drawing as well as a photocopy of a magazine feature about the home from April 1948.

The home had come in a kit designed by draftsman Alpha Sehlin, known for marketing “Affordable Swank for the WWII Generation.” Clark’s own take: “Mid-century for the working class.”

Also appealing was the compact, 950-square-foot floor plan, the third-of-an-acre lot crammed with raised garden beds, and a slower pace of life (locals are “more relaxed and less cutthroat” than in the city, she says). Among other improvements, Clark and her husband refurbished the kitchen and planted a dwarf olive tree in an established mini orchard of lemon, plum, apricot, pear, nectarine, and cherry trees.

She also decorated the walls with paintings, prints, drawings, and textural pieces by artists she finds inspiring, including Robert Motherwell, Kiki Smith, Sonya Philip, ReCheng Tsang, and her 83-year-old mentor, San Francisco artist Myrna Tatar.

Then she turned her attention to the yellow tumbledown shed in the backyard. After it was determined to be beyond rehabilitation, she tore it down and designed a gleaming-white, board-and-batten box to her own exacting specifications.

Measuring 640 square feet with a ceiling that soars to 16 feet at its peak, and large windows in loadbearing places that made Clark’s contractor squawk, the studio is a spry younger sibling to the main house across the courtyard. It features a storage loft, a guest bedroom, a small library-lounge, and a large trussed work table.

It’s here in her self-designed and purpose-built studio that Clark’s maps, fabrics, tracing paper, sewing machine, iron, rotary cutters, and spools of thread are scattered about like decorative objects: the tools of an artist whose work is anything but decorative.