This article was published in the Jan/Feb 2019 issue of Sonoma Magazine.

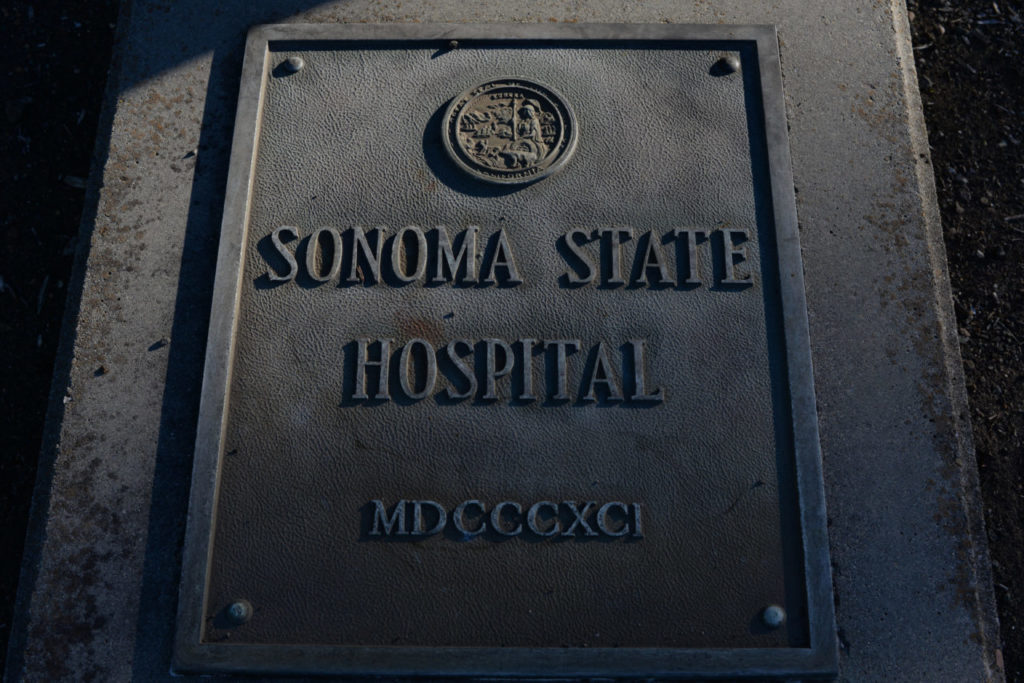

Closed by the state, the 127-year-old Sonoma Developmental Center awaits a new owner and plan for its future. What’s in store for the last big spread of undeveloped land in Sonoma Valley?

The road winding up from the Sonoma Developmental Center toward Jack London State Historic Park is seldom used these days except by fire engines chugging up to a reservoir to fill their tanks for training exercises. Stately oaks stand along each side of the asphalt and wildlife is plentiful: deer trot from meadows into nearby coverts, and acorn woodpeckers yammer and flit from tree to tree. On any given day the road and an adjoining complex of trails are enjoyed by a few hikers, most of them Sonoma Valley residents. Though this is all state land, the fact that it’s open to the public isn’t widely known; it’s not a secret, exactly, but it’s a cherished destination little publicized by savvy outdoor enthusiasts.

Not far from the center, the road skirts a cemetery that has been all but abandoned. Most of the gravestones and markers are missing, and an old metal gate stands as an isolated sentinel to about 1,400 bodies resting under the long, yellow grasses of late autumn. They were residents of the 127-year-old campus, the oldest and largest state facility for California’s most developmentally disabled citizens. For the past three years it has operated under a state closure order, winding down an operation that once involved a workforce of 3,000 employees and about as many residents. The few dozen remaining residents were being moved to community facilities late last year and the buildings locked, with only the power and heat left on. The state called it a “warm shutdown.”

On the map the place is called Eldridge, a town encompassing the developmental center and named more than a century ago for retired sea captain Oliver Eldridge, who was charged at the time with finding a permanent home to care for the disabled. Its stately brick buildings, lush lawns, and tree-lined streets still mark it as a place apart, conceived and constructed in an altogether different era. Its large apron of open space — tightly clustered oak woodlands and shaded streams, stretching up toward the western skyline — has framed the northern end of Sonoma Valley since before Jack London rode horseback through the hills of his nearby Glen Ellen ranch. And today, speculation swirls over what’s to become of the site, which has been eyed for much-needed housing, space for university programs and offices, and other community services.

The closure, however, does not mark the end of the story for the Sonoma Developmental Center, the name given only 32 years ago to the sprawling campus that for much of the last century went by Sonoma State Hospital. At roughly 900 acres, the property in the heart of Sonoma Valley encompasses some of the most beautiful and valuable land in the North Bay. Most of it is undeveloped and constitutes a broad de facto wildlife corridor linking Sonoma Mountain on the west to the Mayacamas Mountains on the east. The 100 or so acres that comprise the developed campus contain 140 buildings, some of historic value, many others requiring an extensive retrofit before any reuse.

But it is a real estate gem that no one apparently wants to claim. Its value — in dollars, natural splendor, and historical significance — is indisputable. Its disposition, however, presents such an onerous maze of bureaucratic and financial obstacles that no viable plan has been devised for its future use.

The state wants Sonoma County to take the property but has been disinclined to pledge the millions of dollars needed to renovate existing facilities and implement a comprehensive management plan. The county, already stretched beyond its means by the 2017 North Bay fires, has backed away from taking responsibility. Conservationists, SDC patient and housing advocates, and others have reached consensus that the open space should be preserved, with “appropriate” development on the existing built-out footprint. But opinions differ widely on what “appropriate” means and no practical means for funding a large-scale remodel exists. The estimated cost of rehabilitating the salvageable fund to deal with infrastructure issues, buildings and electrical, water, and sewage systems amounts to $115 million, according to the state Department of General Services.

Meanwhile, the clock is clicking on the shutdown and eventual withdrawal of state funding. The state’s budget for the SDC was $88.6 million in fiscal year 2013-14, but dropped to $62 million by 2017-18. This year, state support will fall to about $1 million a month for maintenance until July, when the property will be transferred to the Department of General Services for disposition. An extension of the shutdown funding beyond that is possible but uncertain.

The tight deadline has interested parties fretting that the property — the last large tract of pristine open space in Sonoma Valley, one of Wine Country’s most scenic and popular destinations — could be lost or snared indefinitely in a politically driven process that overrides the public interest and discounts the value of the open space.

“The SDC is a diamond in the rough, but it’s still a diamond,” said Susan Gorin, the Sonoma County supervisor whose district includes the SDC and who has helped spearhead the coalition weighing in on the property’s future. “It has great potential for interim and low-income housing, watershed and wildlife protection, recreation and carbon sequestration, even for the development of major conference complexes for climate change, conservation, and water recovery.”

But, aside from being the last unsecured expanse of public property in the valley, the property is also part of the living history of the region. It was once the largest employer in the county and the largest community in the valley north of Sonoma, with everything from its own police force to a self-contained steam-driven power system. The people who lived and worked here were deeply woven into the civic structure and daily life of the region. Honoring that legacy, many agree, must also be a component of any future development plan.

“It’s a tough situation,” said John McCaull, the land acquisition program manager for the Sonoma Land Trust, which has taken a lead role in talks about the site’s future. “It’s clear the state wants to get out from under the property, but they can’t offer enough money for the county to take it on. The county’s position is that it isn’t set up to be a developer, at least for a property with these kinds of issues. The infrastructure is in terrible shape, including the ancient steam system that provides the heating and cooling. The county asked the state for a $150 million contingency but the state turned them down. So we’re at an impasse right now.”

Future use of the property does not call for the scale of care once provided to generations of developmentally disabled men, women, and children. But their long-standing claim to the place must be recognized, say advocates, and to date such acknowledgment has been wanting.

“SDC wasn’t perfect,” said Kathleen Miller, a co-president of the Parent Hospital Association, a group that has served as a strong voice of SDC’s residents and family members. Her adult son recently left the center for a community facility, and Miller said she’s satisfied that he’ll continue to receive good care, though she’s concerned that won’t necessarily be the case for all former residents, especially those with behavioral and severe medical issues.

At SDC, “there were problems, including with the staff at times. But everything considered, it met needs pretty well. It certainly did for my child,” Miller said. “We intend to follow these residents as they move into new homes to make sure they get the best care possible. We’re not going to fade away just because SDC is closing.”

Sonoma Valley resident Walter McGuire, who is president of the San Francisco-based Environmental Policy Center and former director of the California State Office in Washington, D.C., said some groups have made productive proposals for the property. The Friends of Jack London State Historic Park, for example, have offered to acquire and manage the western portion of the undeveloped area that abuts the park, and many community activists are pushing for low-income and interim housing in the developed zone. But such suggestions are tentative and don’t address the disposition of SDC as a whole, McGuire said.

“The state wants to do a complete deal all at once,” he said, noting that officials have turned aside offers to deal with the open space first and the developed acreage later. “They don’t want to approach it in a piecemeal fashion.”

Sonoma State University has been suggested as a lead management partner for the site, but that’s unlikely to happen anytime soon, said Paul Gullixson, the vice president for strategic communications at SSU. It can make sense for a state university to assume authority over a development center, he said, citing Cal Poly Pomona’s annexing of the Lanterman Developmental Center as an example.

“But Lanterman was very close to Cal Poly, and the SDC is about 20 miles from SSU over winding roads,” Gullixson said. “It’s true, SSU is actively seeking out housing for our junior faculty and staff. We just bought a 90-unit apartment complex in Petaluma. But the distance to SSU is significant, and the costs of rehabilitation — including dealing with asbestos, lead, and possibly other toxins in some of the buildings — would be prohibitive, considering the state isn’t at all likely to provide funding. We agree that the open space must be preserved, and there could be good options for redevelopment on the campus. If a role for us becomes clear in the future, we’d like to pursue it, but we just don’t see that nexus right now.”

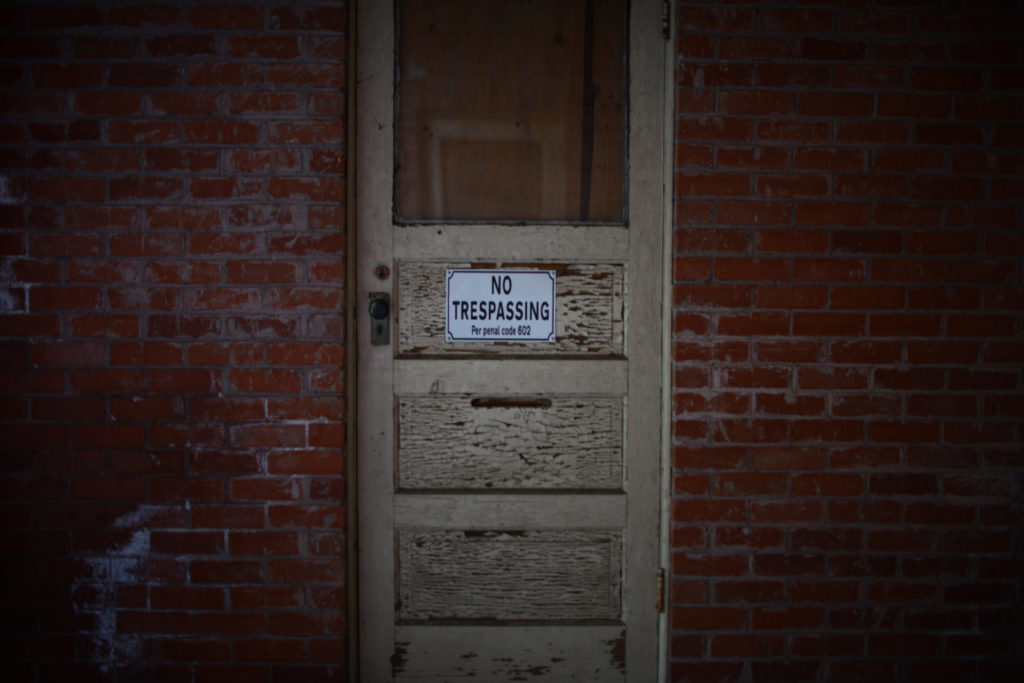

Meanwhile, the state will proceed with its “warm shutdown,” paying about $1 million a month for a skeleton staff that includes police and fire coverage to ensure vandalism and trespassing are kept at bay and basic services are maintained.

The Presidio Trust, the organization formed to oversee the transition of the former Army base in San Francisco into a national park encompassing private homes and businesses, has been floated as a possible model for the SDC. At the time of its decommissioning, the San Francisco Presidio was one of the most iconic properties in one of the most expensive and glamorous cities in the world. It had hundreds of buildings in good condition that drew the attention of thousands of prospective tenants. Even antiquated structures were in high demand: George Lucas tore down the old hospital to build his renowned Letterman Digital Arts Center.

That model holds some potential, say McCaull and McGuire. But while the SDC boasts undeniable cachet of its own, it hasn’t nearly the number of habitable buildings that were on Presidio land at the point of its transition, and the attendant infrastructure is in far worse shape.

Before anything is attempted, a thorough and objective analysis must be done on the developed footprint, say some observers.

“I’ve worked a little in development, and I know a bit about older structures like these,” said Sonoma-based developer and lobbyist Darius Anderson, whose real estate firm, Kenwood Investments, is a leader in the massive redevelopment project envisioned for San Francisco’s Treasure Island.

“I probably tend to look at this differently than somebody who starts out determined to do something specific, like build low-income housing,” he said. “I think the first thing needed is a detailed assessment of the historic value and preservation costs of every building out there so we can determine what has to stay and what can go. Then we can definitively say — for example — how much affordable housing the existing or renovated infrastructure will support.”

Anderson, managing member of Sonoma Media Investments — owner of Sonoma Magazine and The Press Democrat — stressed that he had no current involvement and “absolutely no desire, zero interest,” in working on any SDC project.

“But I live in the valley, I’m deeply interested in the region’s history in general and Jack London particularly, and I want what’s best for the community,” he said. “Whatever happens, we have to be sure of a few things — that we preserve the historic integrity and the open space, and that we don’t create a lot of new traffic.”

Looking into a cloudy future

A good general analysis of possible scenarios for the developmental center is already available. In 2015, Governor Jerry Brown’s administration ordered a decommissioning of the facility amid a string of funding setbacks and scandals at the state’s five developmental centers that involved patient deaths and abuse. Two years later, the state Department of General Services contracted with Wallace Roberts & Todd, an urban planning and design firm, to assess the property.

“We didn’t recommend specific uses,” said Jim Stickley, a principal at WRT. “Instead we focused on ‘possibilities and constraints.’ Among the things that stood out were the remarkable natural resources and the opportunity to encompass those into a regional ecological framework. The property links Sonoma Mountain with the Mayacamas range — it’s an extremely important wildlife corridor, perhaps the most critical linkage for the whole area.”

But the undeveloped portion of the SDC doesn’t necessarily require a completely hands-off approach to retain key ecological values, said Stickley. In certain portions of the property, seasonal grazing or other low-impact agricultural practices could be allowed without negative impacts to wildlife.

The report also identified opportunities on the developed campus to preserve buildings of historic and cultural significance and retrofit others for housing or other uses. Significant constraints exist as well, Stickley said, including the mediocre-to-poor condition of utility networks and the decrepit condition of some buildings.

“Some of the buildings that you may want to preserve the most — such as the brick Professional Education Center in the middle of the campus — are in the worst condition, with the floors literally falling through,” Stickley said. “So in these cases, the challenge is how do you attract the funding and use it to bear the burden of restoration?”

The SDC falls within the jurisdiction of two California state senators: Mike McGuire and Bill Dodd. McGuire’s district encompasses the developed campus, while Dodd’s covers most of the open space. McGuire said legislators and state agencies instituted a three-part process following Gov. Brown’s closure order.

First, state regulators and private stakeholders collaborated to ensure that all SDC’s residents had secure homes and adequate care, the Healdsburg Democrat and former Sonoma County supervisor said. The process is now moving on to its second phase: actual disposition of the land. But this isn’t a standard divestment of state surplus land, which typically involves the expeditious transfer of property to county or city agencies for pressing local needs, such as housing or recreation. Parts of SDC could qualify for either or both uses, McGuire said.

“SDC is a special site both in terms of its beauty and history, and it demands special treatment,” McGuire said. “So we’re having in-depth discussions with the County of Sonoma to determine how to take the SDC into the next century and beyond… My position is that this must be done right, not fast. The community will have a seat at the table the entire way.”

The third phase, McGuire said, will be adoption and implementation of a plan that emerges from that collaborative process.

“One bottom line is that the open space must be protected in perpetuity,” he said. “I think there’s already broad agreement on that.”

Sen. Dodd of Napa concurs generally but is more pointed about the need for the county and local advocacy groups to put some skin in the game.

“Unless the community steps up, it’s hard to think of a scenario that doesn’t involve a developer,” Dodd said. “The costs [of rehabilitating infrastructure and buildings] will be significant. I understand the county doesn’t have unlimited resources, but neither does the state. We do need to let the process play out in determining what gets built. But maybe we should engage with a local developer to work with the community to define the art of the possible.”

Supervisor Gorin has been working for six years with a broad group of community advocates, the SDC Coalition, to forge a long-range development and management plan for the property. Originally, the group hoped to keep the center open, given the critical services it provided to a vulnerable population and its value to the region as a large employer offering well-paying jobs. When it became clear that the center would be closed, Gorin said, she and her allies cooperated on the assessment produced by Stickley’s firm.

Shortly after that report was issued last year “the state told us that the county had to pull something together in a few months to take over the center,” Gorin said. “We were surprised… It’s widely known that the county’s budget and general fund have been depleted by the North Bay fires, that we’re short on staff — that we just don’t have the finances or people needed to take on something like this.”

The state’s declining investment in SDC infrastructure, Gorin said, means the county is ill-equipped to bear the expense of retrofitting.

“It’s time that the community and the Board of Supervisors state publically that the State of California has the responsibility for this site, that they just can’t abandon it or sell it to the highest bidder,” Gorin said. “[The state] has promised strong community support, and they need to follow through. I understand they want to move forward as quickly as possible with as little public investment as possible, but they have a responsibility to shepherd this process with adequate resources.”

The state has been clear about its commitment to a publicly driven process to decide the property’s future, said Monica Hassan, deputy director of the California Department of General Services. “We understand that there is a great deal of community interest — and concern — over the future of the campus: When its future will be decided, how the community will get to weigh in, and what the state of the campus will be in the interim. We understand these concerns and continue to evaluate next steps. Unfortunately, the issue is complicated, and since it is subject to the state’s annual budget process, it will take time.”

So where from here? That, of course, is the crux of the problem. The SDC was integral to the community, its disabled residents, and their families in multiple and interconnecting ways. That value must be preserved in the property’s future, said Miller, the Parent Hospital Association co-president.

Further, PHA members have some specific things they’d like to see implemented, and restoration of the cemetery — an act both material and symbolic — is foremost among them.

“It’s completely abandoned,” Miller said. “There were once concrete markers on the graves, and they’re all gone now. Supposedly, a lot of them were used to shore up some land along a creek. It’s just disrespectful, callous even, what happened there. These were human beings. We want the debris cleared and the markers replaced. We want to turn it back into a quiet, peaceful, and well-maintained place where family members can go and be with and think about their loved ones.”

Virtually all parties involved in the SDC agree that something must be done to forge a new era for the campus. Most are convinced that it will be done. The alternative is hard to fathom. Failure to preserve the open space and develop the campus in a way that serves the community and speaks to a progressive and all-inclusive vision is somehow unthinkable.

“There are no bad guys involved in this,” said Walter McGuire. “Everyone has good intentions. But somebody has to step up and cut the Gordian knot.”