Santa Rosa photographer Kaare Iverson was on a photo assignment for a winery along Dry Creek outside Healdsburg when a colossal construction project caught his eye.

“I found these mysterious wooden pillars sprouting from the edge of the creek,” he remembers. Iverson later learned the pillars were part of a project to create habitat for endangered salmon. “I felt such an immense sense of pride in my community, that we would exert such enormous effort at such expense for conservation.”

Iverson grew up in a commercial fishing family in the Prince Rupert region of northern British Columbia, where a healthy salmon population makes annual returns in prodigious numbers. After moving to Sonoma County, Iverson became curious about the natural history of the Russian River watershed and, he says, “a bit obsessed with the idea that it once held, and could again hold, enormous runs of coho and chinook.”

Sonoma’s Russian River watershed was historically home to hearty populations of native salmon like those Iverson was familiar with in British Columbia. After Russian River surveys in the early 2000s revealed that local species had dwindled to dangerously low numbers, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Sonoma Water and other local agencies have spent the past two decades trying to preserve the unique genetics of native coho salmon.

The contrast between the waters where Iverson grew up fishing with his father and the Russian River, where salmon populations have been so depleted, has led Iverson to consider what it would be like to live in a world without wild salmon. “I know what this place could be like… and I recognize that it’s going to take a considerable shift in public perception to get it there.”

For the project, Iverson photographed at the Warm Springs Fish Hatchery west of Geyserville, home to native coho breeding programs, as well as at several restoration locations in the Russian River watershed. He used both modern equipment and a large-format Ansco camera that, remarkably, once belonged to Ansel Adams. Iverson’s stepfather’s cousin, who worked in a framing shop in Carmel, acquired the camera in the 1980s and later passed it to Iverson.

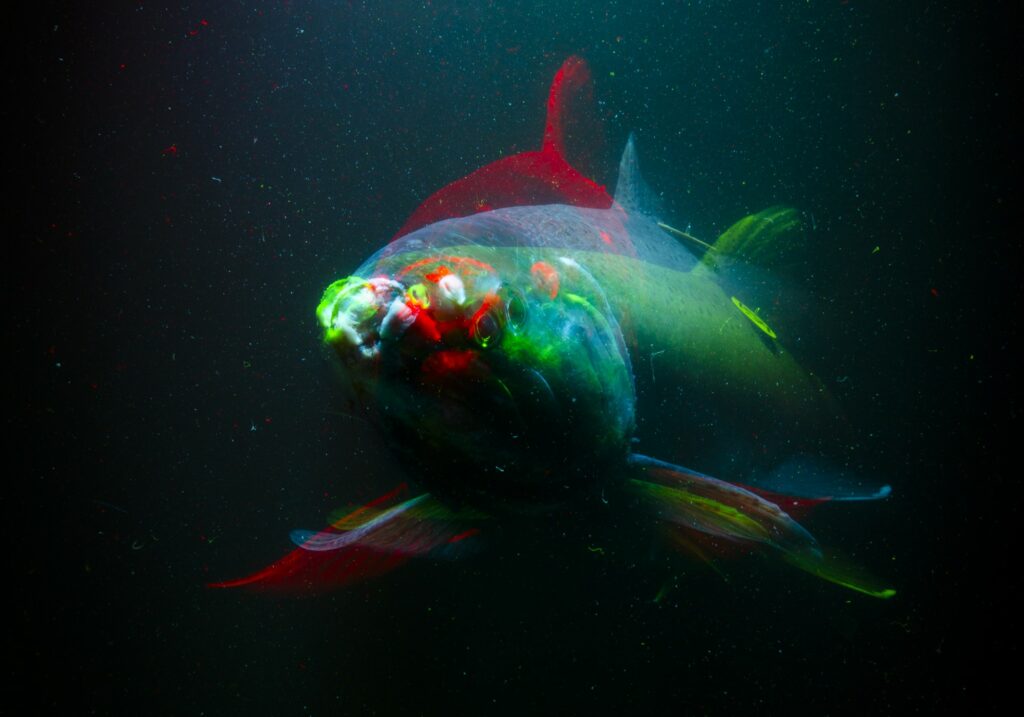

Iverson’s portraits of the salmon — and the people working to save them — convey his belief in treating overlooked populations with the same reverence reserved for charismatic, keystone species like bison and grizzly bears. Iverson says he wanted to create portraits “that give these fish a sense of personality, going so far as to anthropomorphize them in a way that feels human, personal and conversational.”

Beyond composing his alluring images, Iverson brings a strong sense of purpose to the work, connecting viewers with the roots of their natural history — “so that the knowledge of what this watershed could be is not lost, and so that we can all remember what it is we should be fighting for.”

Precocious Jack

A precocious jack is a salmon that reaches sexual maturity at age two rather than the typical three years, a natural adaptation that leads to greater genetic diversity.

Iverson had been granted a single day to shoot at Geyserville’s Warm Springs Fish Hatchery. But the water that day was filled with silt, too opaque to create the portraits he’d envisioned. Fortunately, a biologist remembered they’d frozen about 20 gallons of clearer lake water, “just enough to fill the aquarium we were using to hold the fish,” Iverson recalls. The lake water still contained a small amount of silt; those are the flecks in the photo.

“After a few test images, I realized I could modify my lighting such that the silt would catch the light and create a bit of a vignette around the fish,” he says. “And it added depth and a sense of the water itself that I appreciate more than the original idea.”

A Brighter Dawn

Water trickles into one of dozens of new enhancement sites along Dry Creek. Seeded with native flora and studded with wooden poles, this development will form a year-round, cool-water refuge for young salmonids and other native animals. Before the first sprout broke through the burlap, the location was already occupied by fish-eating birds, a sign of the ecosystem coming back to life.

“I loved watching this site develop,” Iverson says. “To see a landscape torn apart by machines meticulously reassembled with engineered waterways, and ultimately repopulated by native animals, was inspiring. An untrained eye could easily mistake this site for a devastated clear-cut landscape, rather than a setting for potential ecological energy. There’s a definite sense of momentum.”

Handle with Care

At Warm Springs Fish Hatchery, biologist Ken Leister grips a female salmon. As part of restoration efforts, mature female salmon who return in winter to the Russian River watershed to spawn and die are instead euthanized at the hatchery. Their eggs are harvested and mixed with the milt, or sperm, of male salmon with desirable genetics, and the resulting juvenile fish are returned to local waters.

Leister holds the female salmon gently — any blood or fluids that contact the unfertilized eggs could damage them. “Each egg is important to the survival of the population. The margin for error in the recovery of these fish is slim,” Iverson says. “There’s a preciousness to how all this biological potential is handled, love and care and death and rebirth all happening at once.”

One Fish, Two Fish

A Sonoma Water staffer cleans the viewing window at a diversion dam below Wohler Bridge on the Russian River. This narrow passage in the dam’s fish ladder allows for an accurate count of returning fish, including both hatchery-bred fish and those born in the wild. Iverson had hoped to photograph fish going up the ladder, but few fish have returned in recent years. When he made this image in early 2023, it was already apparent that the coho that year were either unusually late in their return, or perhaps not returning at all.

“As I watched them clean the viewing window, I was immediately struck by the mix of futility and hope these scientists were harboring,” says Iverson.

Breeding for Diversity

Biologist Emily Van Seeters places fertilized coho eggs into spawning racks at Warm Springs Fish Hatchery. In winter, during spawning season, the racks are fed with a constant stream of fresh water coming out of Lake Sonoma. Each female is spawned with up to four different males for genetic diversity, according to the California Department of Fish and Wildlife.

A juvenile coho raised at the hatchery is weighed before being fitted with a tracking tag. The hatchery’s conservation work was honored as part of the Lake Sonoma Steelhead Festival on Saturday, Feb. 8 (steelheadfestival.org).

Human-made “Natural” Habitat

Large-scale dams such as Warm Springs are primary culprits in the decline of salmon populations. But as water temperatures rise in local creeks due to climate change, cooler water released from the depths of the reservoirs can help salmon. The problem is that high flows also wash away the gravel beds that females need for spawning, as well as stands of woody debris where juvenile salmon can shelter and grow.

“Without a place to rest, small fish would be blasted out into the main stem of the river where they stand little chance of surviving,” Iverson says.

Local agencies and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers are driving wooden poles into the riverbank and piling up brush to simulate natural habitat, as well as installing metal blockades to slow the course of the water. The first 3 miles of a planned 6-mile restoration along Dry Creek is nearly compete.

Cycle of Life

This hatchery salmon, after it died, was planted in Green Valley Creek by volunteer Doug Gore. Salmon typically spend their first year in a river or stream before migrating to the Pacific Ocean to live for two years. In the winter of their third year, they return to the stream where they originated to spawn and then die. Their bodies become a part of the food web, providing nutrition for small invertebrates, younger salmon and otters.

Gore tells Iverson he’s seeing less invertebrate life in the streams he visits, a concern echoed by biologists worldwide. And without the local efforts of Gore and other passionate conservationists, it’s possible that native coho might already have disappeared entirely from the Russian River watershed. That’s a world difficult to imagine. But Iverson’s images of the salmon and those seeking to steward their recovery offer hope for a more bountiful, flourishing future.

Correction (Feb. 21, 2025, 2 p.m.): This story has been updated to correct the type of equipment shown in photos for salmon habitat restoration projects.