Rick Oginz’s house sits on a steep hill on the lowest slopes of the Mayacamas Mountains, rising from and overlooking the Valley of the Moon. It sits just high enough to attain a modest yet clear view of Sonoma Mountain on the other side. Over there, to the north, is Jack London State Historic Park and the ruins of Wolf House, the famed author’s ill-fated dream home that captured Oginz’s imagination and became the subject of more than 20 of his paintings over the course of five years. They recently exhibited inside the park’s House of Happy Walls Museum.

The House of Happy Walls, incidentally, was where London’s widow, Charmian, lived from 1935 until her death in 1952. She might’ve been living in Wolf House during that period after the author’s death in 1916 at the age of 40, except that their forever home — which was to include a sizable workshop and library — burned one night in 1913 just before it was completed, leaving behind only its massive stone walls.

Somewhat like London’s home was intended to, Oginz’s abode — which he moved to in 2020 after living and working in Los Angeles, Oakland, Toronto, and London — serves as a workshop, studio, and gallery.

If Oginz squints in the right direction he might imagine peering all the way across the valley, through the redwood canopy, and into what’s left of Wolf House. He didn’t move here just for an almost-view of an incinerated mansion. “I looked around for a house that would be close enough to San Francisco, and I found this,” he says, but there’s no denying his reverence for the site. “It was the high point of civilization but returned to nature immediately on completion. Its walls and arches reveal ambition that was denied.”

Beyond his aesthetic and symbolic interest in Wolf House, Oginz is a longtime admirer of London’s fiction, having read about a dozen of his books. “His overarching theme is the contrast between civilized and wild,” Oginz explains. “Like a dog becomes a wolf, or a wolf becomes a dog. And, so, the Wolf House, before our eyes, is returning to nature, with all the vegetation growing on it. In one of the fireplaces, there is a pretty large beehive, and you can see bees really active around it.”

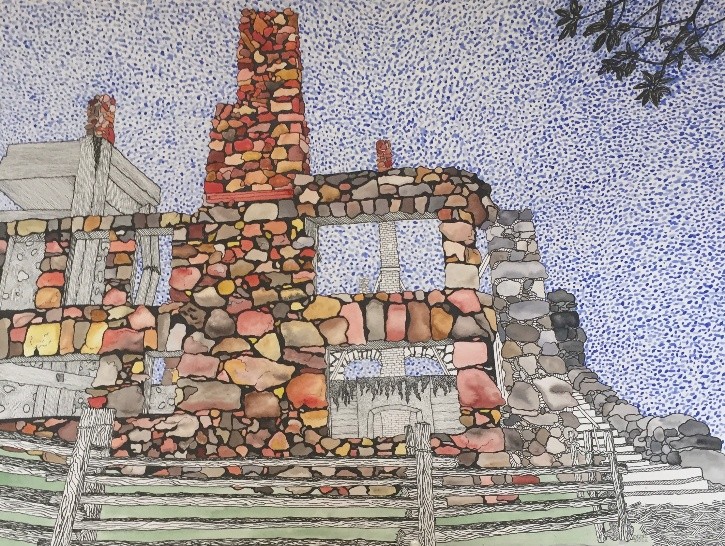

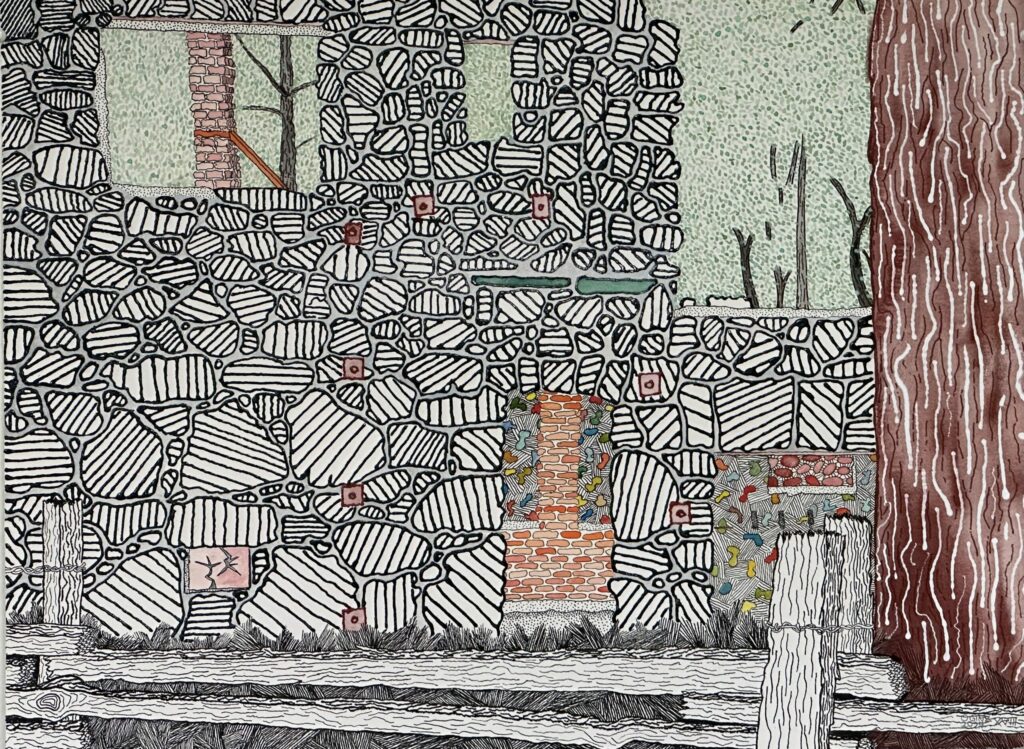

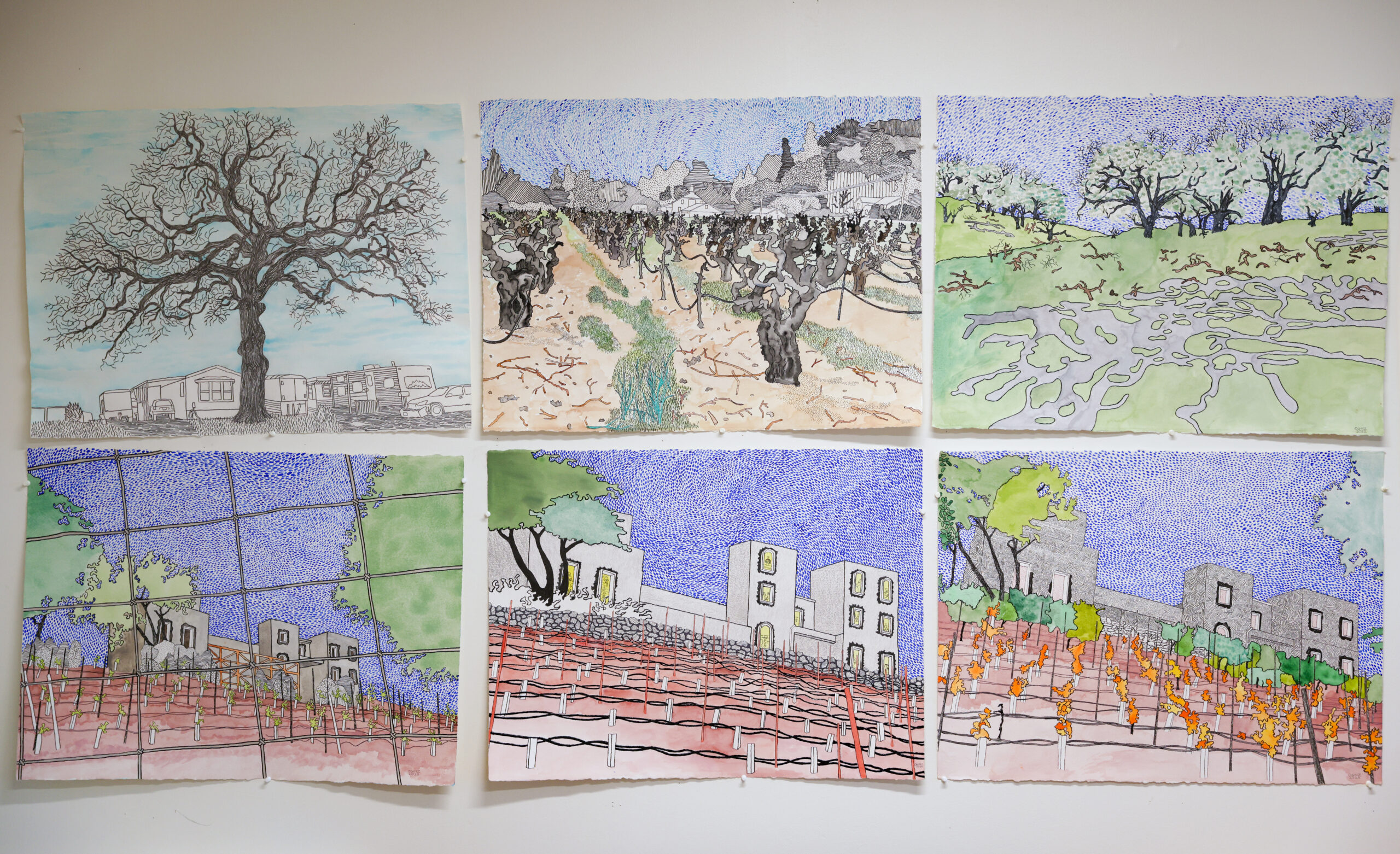

His mixed-media renderings of different aspects and views of the Londons’ house on 22” by 30” watercolor paper combine bold, almost cartoonish color with simple, sketch-like linework that occasionally reveals every stroke or stipple of ink. It’s a divided approach the lifelong artist has used before, but that’s particularly well suited to Wolf House: subject and style both appear simultaneously unfinished and perfect as they are.

In fact, the site is conflicted to its core, positioned at the intersection of past and present, dream and reality, home and ruin. “My house will be standing, act of God permitting, for a thousand years,” London wrote during its construction, a sentence that now reads more like an order than the hubristic prediction history has revealed it to be.

Oginz plays with this further by including steel braces and other supportive structures in his drawings, as well as the wooden and chain link fences that surround and protect Wolf House. This lets the viewer experience the site as Oginz did — or as would any member of the general public — and also captures its fragility.

The Wolf House works are thus documents that interpret and preserve the landmark at a specific point in time. The structure itself may not be standing in another 900 years — certainly not as it looks now — but perhaps Oginz’s renderings will, somewhere, in some digital cloud. So will his illustrations of architectural landmarks in other places he’s lived and worked: the Port of Oakland, Tribune Tower, and Bay Bridge; the Watts Towers in Los Angeles; the CN Tower in Toronto.

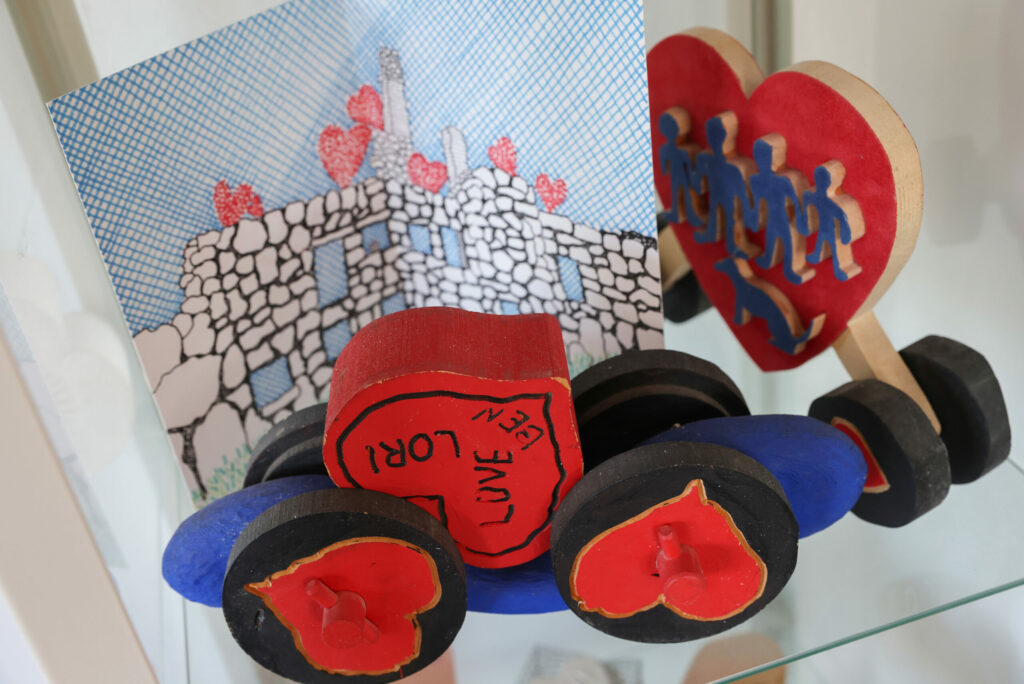

His vast repertoire, dating to the late 1960s, covers many other subjects: industry, technology, transportation, science, biology, nature. He’s proficient in myriad mediums, methods, and materials, having practiced drawing and painting, sculpture and ceramics, wood and metalwork side-by-side for decades. In fact, after Oginz’s exhibition at the House of Happy Walls he began making ceramics at the Sonoma Community Center down the road — in some cases bringing to life three-dimensional designs he’d already drawn.

“My work is autobiographical and journalistic,” he says. “I react to my literal environment by representing it in graphic and/or sculptural form.” Oginz’s reactions to his external environment in turn make up his most intimate one, as the walls, floors, and shelves of the rooms and hallways of his home have become a de facto gallery, displaying a rotating selection of his works spanning much of his career. A framed piece from the Wolf House series is on the west wall, facing Sonoma Mountain.

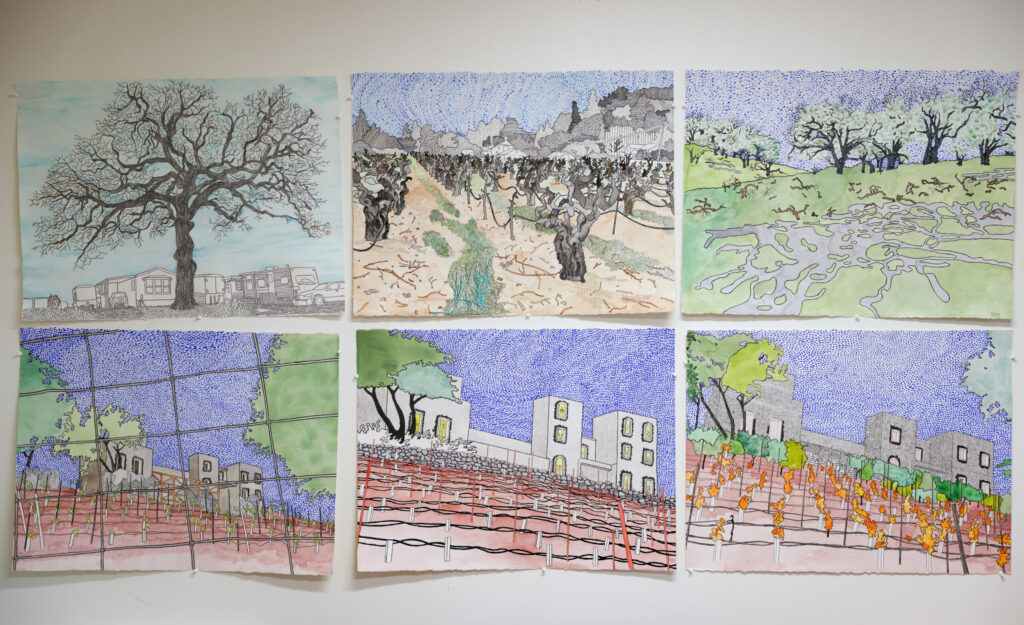

Downstairs, Oginz’s drawing studio is both an archive and a workshop in itself. There, he spends hours on the fine, black linework that defines his style. Displayed on one wall is a series of paintings of his neighborhood’s landmarks, of sorts, depicted throughout the seasons: large, gnarled trees; rows of old vines; and a nearby wine estate under construction that, like Wolf House — and perhaps all of existence, seems in Oginz’s view to be perpetually incomplete.

“It looks very ominous to me, because you can’t really tell if it’s under construction or destruction,” he says. “It’s in that state of flux.”

Learn more at rickoginzart.com.