(photography by Erik Castro)

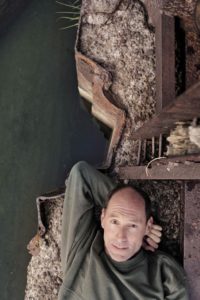

Standing on the dusty banks of the Russian River, Don McEnhill surveys the mostly dry gulch that is Del Rio Woods Beach near Healdsburg in a record drought year.

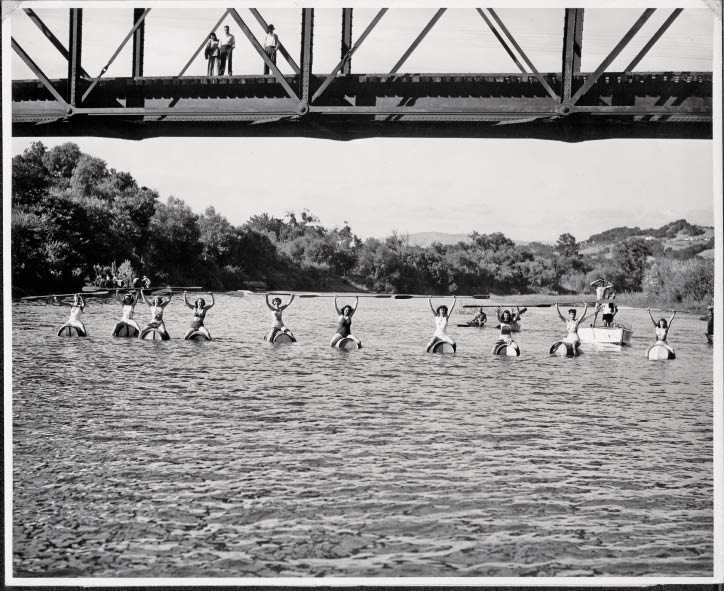

Almost forgotten in the wide expanse of rocks, the speckled ribbon of current, maybe 15 yards across and a foot deep, resembles a creek more than a river. A rusty skeleton of a dam, hunkered down like an abandoned flatbed truck, sits in the middle of the water. Young willows bob for balance in a sandbar as the wind rattles through cottonwoods across the river. A handful of teenagers in bathing suits have spread out towels a few feet from the water.

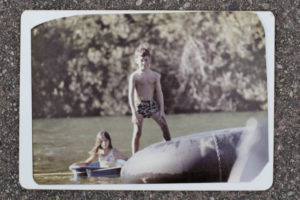

“This was where you could be Huck Finn for the summer,” McEnhill says, looking back on his childhood. “If you didn’t have a canoe, you’d find a log and roll down the river or you’d spend hours just playing with green tree frogs that showed up on the river that morning. You were only limited by your imagination.”

Every summer, just before the dam went up on Memorial Day weekend, a neighbor would drive his tractor along the river bed, knocking on cabin doors and asking owners if they wanted their “beach” bulldozed. For a nominal fee, he’d push gravel and sand to the edge of their properties so that when the water rose from the Del Rio dam, a sandy beach would be waiting at the bottom of the paths that led down from cabins, which had names such as “Jim’s Folly” and “Laf-a-Lot Lodge.”

Now 51, McEnhill was only 7 days old when he first heard the rolling waters of the Russian River, lulling him to sleep in a playpen on a beach six lots up from where he’s standing now. Back then, in the early 1960s, the river was the epicenter of town life in Healdsburg. It’s where kids learned to swim, row a boat and later chase after girls (or boys).

“That’s where you saw everybody — down at either Memorial Beach or Del Rio,” remembers McEnhill, who now does everything he can to preserve the river as executive director of Russian Riverkeeper, a nonprofit dedicated to the health of the watershed. “If it got up in the 90s or over 100 degrees, everybody would literally give up whatever they were doing and show up at the river.”

Summer wine and cocktail hour was on the river. Just in case anyone ever forgot, McEnhill’s Aunt Mary scrawled the “McInerney’s Gin Fizz” recipe on a kitchen wall in the family cabin (nicknamed “End-O-Care”) more than 50 years ago. The drink includes a lemon, “a little sugar,” “1 egg to 2 shots gin” and a kicker at the end: “Then shake like hell.”

Today, the river is hardly the main attraction in town. People flock from all over the world for the tasting rooms and farm-to-table restaurants around the Healdsburg plaza, most only catching a glimpse of the river when their vehicle crosses a bridge. There are locals who have lived their entire lives only miles from its banks and have never soaked their feet, much less splashed, in its waters.

Coho salmon and steelhead trout don’t return in large numbers anymore, but river otters are making a comeback. Old-timers will tell you the water is not as clear as it once was. The last documented freshwater shrimp were caught in 1970 and the last green sturgeon was hooked under Hacienda Bridge near Forestville in the late 1980s.

Yet the Russian River is still a lively summer draw for more than 1 million visitors a year and an adventure getaway for many families. It’s also the last common bond that connects disparate communities like Healdsburg, Forestville, Guerneville and Jenner.

When summer rolls around every year, memories come back in currents for those who grew up on the river. Linda Burke, of Burke’s Canoe Trips in Forestville, remembers getting her “river feet” during hot summers as calluses quickly formed on her soles from the baking river rocks. Suki Waters will never forget learning to harvest the dogbane plant to waterproof homemade fishing line with her Native American grandmother in Jenner. Guerneville historian John Schubert recalls sun-soaked summers in “the fabulous ‘50s, before everything went to hell in a handcart.”

As Clare Harris, the 93-year-old owner of Johnson’s Beach in Guerneville, puts it, “The river is in our blood. It runs through all of us.”

—

From its headwaters south of Willits in Mendocino County, the Russian River snakes 110 miles through gorges and vineyards, across dams and around sandbars before spilling into the Pacific Ocean at Jenner. The Southern Pomo called it “Ashokawna” to describe “water to the east.” The Spanish gave it names such as San Ygnacio and Rio Grande. But it was the Russian name, evolving from “Slavyanka,” that stuck.

As the river rolls south through Healdsburg, past Veterans Memorial Beach where McEnhill and others learned to swim in Red Cross classes, it narrows to its thinnest and least-traveled stretch, surrounded by gravel pits and vineyards. There are just two public access points (at Wohler Bridge and Riverfront Regional Park) in more than six miles, until one reaches the slow waters near Forestville, where Linda Burke grew up among virgin redwoods that tower over the campground and canoe rental business her family founded in the late 1940s.

“I learned to swim here at about 2 years old,” she says, sitting in a fold-out chair overlooking the gently rippling green water. “My folks taught me right here at this very beach. We were tough kids to keep out of the water, so my parents figured 2 is very young, but let’s teach them now.”

Before long she was tying together logs with her siblings to make rafts, fishing with string and frankfurter bait for crawdads, and “frogging” with high-powered flashlights at night.

“I remember in the summer this beach would be filled with hundreds of people, beach blanket after beach blanket,” Burke recalls. “And the kids would run back from the hot-dog stand and jump from blanket to blanket, because the sand was so hot in the noon-day sun. I don’t care how tough you were, you couldn’t make it back without using people’s blankets.”

On the river, a guy glides past on a stand-up paddleboard. Looking back, Burke, 63, remembers the dance-hall-turned-roller-rink where she worked summers, as well as the horse stables and restaurant/cocktail lounge with redwood trees growing through the roof. Before she was born, her parents ran the Mirabel dance hall that held 2,000 people — the largest ballroom north of San Francisco at the time — and booked top performers including Duke Ellington, Helen Forrest and the Dorsey Brothers.

When Burke was a kid, pop crooner Bobby Darin dropped in for lunch one afternoon, but never sang. The resort is long gone, but she still runs the bustling family canoe rental business every summer.

“Times come and times go,” Burke says, “but the majesty of the river is still right here.”

From Forestville, the waters flow beneath the largest grove of redwoods on the river as it slows to a murmur and eases past Rio Nido (pop. 522), where Clare Harris’ family took over the Rio Nido Resort in 1928. It included 100 rentals (cabins and tents), hotel, dining room, bar, movie theater, bowling alley, outdoor stage, fortune teller, soda fountain, ballroom, dress shop, grocery store and service station, luring visitors far and wide.

In summer, the train from Petaluma via Fulton would arrive at the Guerneville station at 5 p.m. every day and hundreds of Sam Francisco tourists would pour out and head for the last rays of sun on the beaches. It was a “more primitive river back then,” Harris remembers, with more horses than cars, wooden sidewalks, and no television, refrigerators nor conventional swimming lessons.

“I was 6 and we were in a rowboat and my father told the lifeguard, ‘Teach him how to swim or he can’t be around the river.’ So the lifeguard threw me out of the boat and kept the boat about 6 feet from me as he kept rowing. That’s when I learned how to swim.”

In those days, Harris explains, “You wore a full bathing suit like a kid’s overall and women wore bathing suits down to their ankles.”

During the 1930s and 1940s, some of the biggest summer nights swayed beneath the resort’s iconic winking moon sign as big bands led by Harry James, Buddy Rogers and Glenn Miller played as the Harris family’s Rio Nido dance hall. By age 18, Harris was helping run the ballroom, collecting 25-cent tickets every night.

“The girls complained about the fellows showing up in dirty corduroys when they’d have nice white dresses on,” he recalls. “So we told (the boys) they couldn’t come in.”

On this day, he’s at Johnson’s Beach Resort, which he’s owned for 47 years. A tractor plows back and forth, getting the sand ready for opening day. Harris has seen the river change quite a bit over the years. The dam used to go up Memorial Day; now it’s June 15.

“The river has been filling in for years. It’s shallower now,” Harris says. “It was much clearer then, too. You could look down and see your feet. And there’s not as much flow as there used to be.”

But the biggest difference?

“You don’t hear the frogs anymore. It would sound like there were thousands of them, almost like a symphonic orchestra. Not anymore.”

Coming of age on the river in the 1940s and ’50s, John Schubert was a city kid who quickly shed his skin each summer and became a river kid. His earliest memory goes back to 1941 or 1942 when as a 4-year-old he made the maiden trek north and “I just remember it took forever to drive up here from San Francisco.”

A saloon owner in San Francisco, his grandfather built the family summer cabin in 1920 in the vacation retreat of Guernewood Park, just south of Guerneville. Learning to swim across the river by age 12 and later tack a “lateen” or triangular sail mounted in a canoe, Schubert quickly became a river rat.

“You had groups of kids who saw each other every summer,” he recalls. “There was the Rio Nido group, the Guerneville group, the Guernewood group and the Monte Rio group. During the winter, they were all rivals. You had kids from Mission High and Balboa, Galileo, Washington or Lincoln (in San Francisco). But when you came up here during the summer, you were all buddies.”

On a cloudless weekday morning, he’s sitting on Johnson’s Beach, across a quiet river from where the community once held its last-gasp summer celebration every September, known as the Pageant of Fire Mountain.

“It was totally politically incorrect,” Schubert says. “They had teepees and white people dressed up as Native Americans with war paint, and buses (filled with people) would come up from the city just to see this.”

Clare Harris’ niece, Laura Wilson, was only a kid at the time, but she remembers being enthralled by the annual pageant onstage across the river. “My father and mother and all their friends were in it, dressed up like Indians.”

The play followed a princess (played many times by “the beautiful Kathy Genelly”) who is kidnapped by a lusty brave. They’re from warring tribes, but eventually fall in love and get married.

“One of the elders officiating the marriage would say, ‘Oh great spirit, give us a sign’ and the local fire department would light off flares and the whole mountainside would light up red,” remembers Schubert. “It’s one of those things you can’t imagine anyone ever doing now.”

—

From Guerneville going south, the river hooks and bends, taking on brackish water as it turns to estuary habitat for juvenile halibut, starry flounder, Dungeness crab, harbor seals, eel grass and pelicans. Flowing beneath the Monte Rio Bridge and past Duncans Mills, it pools in a wide mouth at Jenner, where Suki Waters grew up learning everything she could from her Kashia Pomo grandmother. Josefa Navidad Santos was born in 1904 in the native village at Goat Rock Beach and lived part of her life on Penny Island.

“The island was our family playground,” Waters says.

As a kid, she would row to the island and explore its every cove and trail, retracing the ruins of the old farm that once thrived there. She spent summers fishing for cabezon and “rock-picking” for abalone in tide pools north of the river mouth.

“You knew summer was coming when the little Dungeness crabs would start showing up in April and they started their molt,” Waters remembers. “Then the shad would come in and you’d see them popping in the water and scaring other little fish. Harbor seals have had their babies by then and the males start coming in just as summer starts for the mating season.”

On this evening, she’s huddled on the leeward side of the state parks visitor center on the water, taking shelter from intense winds coming off the Pacific. Penny Island lies directly across the river. Family lore has her great-great aunt reaching into creeks so thick with salmon she “could pull them out with her bare hands,” to fillet and cook dinner for mill workers. Her Uncle Pio, the story goes, was once nearly pulled out to sea by a giant octopus more than 10 feet long, after he reached blindly into a tide pool.

These days, Waters, 53, runs the kayak business WaterTreks Eco Tours in Jenner and takes clients, many of them students, on the water to pass on her appreciation of nature to the next generation.

“When you see the amazement on the faces of 35 science students, it’s worth every second,” she says.

From her grandmother, she learned to harvest huckleberries and make jam. She was taught how to dig for clams with a coffee can and flash-fry sea lettuce picked off the top of rocks, so that “if you do it right, it just crunches and melts in your mouth, and if you don’t do it right, it’s rubbery.” She caught eels in the river and cut them into steaks before putting them in the pan, so the unwanted skin would curl around the edges and could be pulled off.

Back then, respect for the river “was just ingrained in us,” Waters says. “It’s been a through line, a continuous force, from a hunter-gather society, to logging and fishing, to tourism and now hopefully to teaching people about their surroundings and passing on the things my grandmother once taught me.”