On a busy summer weekend, tens of thousands of visitors are drawn to our Sonoma Coast, a rugged environment of land and sea where a single moment of questionable judgment can quickly evolve into a life-threatening situation.

The job of keeping everyone safe falls to a shockingly small corps of firefighters, sheriff’s deputies, and park rangers operating within a tenuous web of overlapping jurisdictions. Somehow, they manage to keep the summer from descending into chaos.

It was a run-of-the-mill ropes operation on the Sonoma Coast—which is to say it was complicated, technical, and dangerous. A Mendocino County resident had stopped for a bathroom break about 8 miles north of Jenner during a nighttime drive in the summer of 2016, and had tumbled down the rocky cliffs in the dark. Members of the all-volunteer Timber Cove Fire Protection District received the call around 10:12 p.m. and quickly set up a system of ropes and pulleys.

Two firefighters harnessed in and lowered themselves into the void. The victim’s family wasn’t sure exactly where she’d gone over the edge, and it took two hours of drifting and scrambling to locate her. Finally, Timber Cove Fire training officer Nichole Lynn found her huddling in a bush.

“She was a little cold, definitely scared, and (had) just a few minor scrapes to her face and her nose from sliding down the rock,” Lynn told The Press Democrat at the time.

It may be a typical medical call, but we just had to hike a half-mile to the beach to get to it. There’s always another layer of complexity.” – Fire District Captain Justin Fox

The relieved klutz licked the firefighter’s face all the way back to Highway 1. Marshmallow was a 35-pound pit bull puppy with a lot to learn about safe pooping practices. The pet owners resumed their drive home, and the Timber Cove crew added one more happy ending to the vast annals of Sonoma summertime calamities.

The warm months are here again, bringing waves of awed visitors to this spectacular coastline. And with them will come capsized kayaks and grounded boats, road-rashed cyclists and limping hikers, victims of dehydration and cardiac arrest, swimmers caught in riptides, cars deposited onto rocky ledges they were never meant to visit and any number of random mishaps that become all but inevitable when you set loose a horde of carefree revelers in an environment of rugged land and sea.

In 2019, before the Covid pandemic took a bite out of tourism, Sonoma County welcomed 10.2 million overnight and day visitors. Not all of them came between Memorial Day and Labor Day weekends, and not all ventured to the coast. It just felt like it.

“As early as noon sometimes, our lots are maxed out—what we call full visitation,” says Tim Murphy, a ranger at Sonoma Coast State Park.

The job of keeping these thousands of daytrippers safe falls to a shockingly small corps of first responders. At any moment during the summer, the on-duty staff of firefighters, cops, state and regional park rangers, California Highway Patrol officers and Coast Guard personnel patrolling the Sonoma Coast might amount to a few dozen.

They cover a twisting, 50-mile stretch of California Highway 1 that unwinds from Bodega Bay north to Gualala. Their beat is a puzzle of beaches, rocky ledges, muddy bays and estuaries, campgrounds, city streets and seaside hills veined with dirt trails— locations difficult to access. “It may be a typical medical call, but we just had to hike a half-mile to the beach to get to it,” says Justin Fox, a Sonoma County Fire District captain at Station 10 at Bodega Bay. “There’s always another layer of complexity.”

And of course, there is always the undulating power of the Pacific Ocean, which lures you with its beauty but cares little for your safety.

It’s a lot to handle. Summer is its own brand of mayhem at the coast for one major reason: There are so many more bodies to be bruised, scraped, and scorched. In other words, for emergency rescuers at the coast, the wild card is humanity itself.

“You get 5,000 people on a beach—that’s our target hazard,” says Station 10 assistant fire chief Steve Herzberg. The vast majority of calls to the Bodega Bay station, he says, are for illnesses and injuries that could happen anywhere, anytime: heart attacks, pneumonia, slip-and-fall fractures, and the rest of life’s painful embarrassments.

For Erich Lynn, chief of Timber Cove Fire District—and father of Nichole, renowned pit-bull puppy rescuer—the hardest thing about a summer emergency can be getting to it. More than half of his station’s calls, he figures, put his trucks on Highway 1. It’s a curving two-lane route with narrow shoulders and too-few pullouts, and it’s packed in summer.

Lynn says a lot of drivers freak out when they see the flashing lights behind them, and just stop in the middle of the highway, clogging up the response. Don’t get the man started on cyclists. “Bicyclists, they just don’t listen,” Lynn says. “They don’t pull over, they don’t stop. And sometimes you’ve got five or six riding together. Once you pull out to pass, you’re committed to the whole string.”

While acknowledging the challenges they encounter, first responders tend to project a similar theme: The system works. These folks have your back, even when you’re floating atop 200 feet of ocean.

The range of “situations” they face regularly is limited only by the imagination and questionable judgment of beachgoers.

Station 10’s Justin Fox recalled an incident a few years ago that seemed almost comical, right up to the moment it turned dire. Firefighters received a call about a citizen in distress. They scoped the ocean with their binoculars, and there he was: a young adult, in shorts and tank top, piloting a pink floatie shaped like a unicorn. He had drifted a halfmile south, and away from the beach. The unicorn was presumably bound for Mexico before they collected him.

In June 2019, a 54-year-old woman drove off a cliff just north of Salmon Creek. Investigators suspected it was a suicide attempt. She survived the crash, crawled out a broken car window before her vehicle burst into flames, and swam out to sea, where she was rescued by a firefighter from Station 10 in Bodega Bay.

In August 2021, a man and his six dogs (including five 4-week-old puppies) were rescued by the Coast Guard near Driftwood Beach, 9 miles south of Bodega Bay, after his boat lost power and he drifted in the ocean for a night. And last June, a driver in a Honda Civic went off the side of Highway 1 and rolled about 25 feet down a cliff just north of Russian Gulch State Beach.

If you’re wondering—yes, alcohol does play a significant role in much of this madness. That’s true anywhere. But it doesn’t help to have approximately a billion liters of available, world-class wine between Santa Rosa and the Sonoma coast.

“I don’t drink, so I can smell alcohol from 10 feet away,” says Timber Cove’s Erich Lynn. “People just get bored when they know the road so well. They get a six-pack in Jenner and head home. And a lot of people camp, drink all weekend and then drive home.”

Faced with such a panoply of unfortunate events, it doesn’t help that the interlocking teams of first responders are getting smaller.

When ranger Tim Murphy transferred from Orange County’s Huntington Beach in 1999, his State Parks division had about 20 sworn officers, he says. Now they’re down to eight, handling a busy jurisdiction that stretches from Bodega Bay north to Salt Point State Park, and inland to Austin Creek, including several campgrounds that must also be monitored. “It does take a toll in terms of a lot of overtime work,” Murphy says. “Call volume has gone up, and we have less officers to cover it.”

Erich Lynn says his fire department in Timber Cove historically had 21 to 23 on-call fire volunteers. He has 18 now.

To meet the coverage challenge, coastal emergency crews throw specialization and territoriality out the window. Agencies here tend to do a little bit of everything, working hand in hand with one another in overlapping jurisdictions.

They certainly do at Station 10. It’s like any other firehouse in America, except this one is perched on a hill with a view of a sliver of Bodega Bay. Visitors are often greeted with the sound of barking seals, carried in on the breeze.

Calling Station 10 a fire department is a bit like referring to George Clooney as a tequila salesman. The description is accurate, but it isn’t necessarily the main thing they do. According to Steve Herzberg, the Bodega Bay firehouse responds to about 20-30 fires a year, compared to 25-40 marine rescue incidents.

That’s thanks in large part to Fox, who helped create the station’s boats program a decade ago.

The Bodega Bay fire crew, a volunteer company until Sonoma County Fire District absorbed it in 2022, was always around the water, of course. Until 2012, however, their jurisdiction more or less ended at the surf line. That didn’t make any sense to Fox, who noted that the commercial fishing fleet anchored at Bodega Bay makes up a big part of the town’s tax revenue. Weren’t the men and women of the local fleet entitled to the same level of care as shop owners?

To meet the coverage challenge, coastal emergency crews throw specialization and territoriality out the window. Agencies do a little bit of everything, working hand in hand across overlapping jurisdictions.

Staffing and maintaining a boat program wasn’t an easy sell for a community-supported volunteer fire department. Why do we need this, residents would ask Sean Grinnell, the station chief at the time. “Because we have an ocean,” Grinnell would answer.

Indeed they do, and it’s a squirrely one. Riptides. Side currents. Sleeper waves. Rocky shoals and sandbars. Drunken boaters. Water temperatures in the mid-50s throughout much of the summer. Beneath that soothing surface lies a video game full of risks.

Not every visitor answering the siren song of Sonoma’s coast understands the nuances of this stretch of the Pacific. That can be true especially of those escaping 100-degree days in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, or vacationers more used to the smaller waves and gently-sloping shores of Santa Monica or the Eastern seaboard.

“While some spots on the coast are quiet and sort of calm in appearance, as far as the water is concerned, it’s still the Pacific Ocean,” says Sonoma County Sheriff’s Office deputy Rob Dillion. “And our coast can be particularly rough. There are scenarios where the weather is absolutely beautiful, but the swells and the water are turbulent. You’ve got currents moving through. People get themselves in trouble. And the ocean is not forgiving.”

There is a Coast Guard station in Bodega Bay, too. The military post has larger boats, including an 87-foot patrol boat, and takes the lead on search-and-rescue operations. The Coast Guard is also charged with ocean law enforcement, in the rare event it’s necessary.

Station 10’s smaller craft can perform shallow-water operations, and unlike the Coast Guard, Station 10’s rescue crew includes paramedics. The bigger of its two craft, not surprisingly, also has firefighting capabilities. It’s the only technical fireboat between the Golden Gate Bridge and Humboldt/Arcata Bay in Eureka.

Seagoing entities from Station 10 and the Coast Guard are frequently aided by Henry 1, the all-purpose emergency helicopter operated by the Sheriff’s Office.

The chopper is stationed at the Charles Schulz-Sonoma County Airport in Santa Rosa and is responsible for a huge coverage area. But Henry 1, like the rest of us, winds up spending a lot of time at the beach during the summer. In fact, the Sheriff’s crew flies regular patrol runs—west along the Russian River from the airport, down the coast, around Bodega Bay and back.

The Henry 1 pilots, Dillion says, are trained to fly in winds that would ground many helicopter pilots. It’s one of the few air units in the region capable of longline rescues, those made-for-TV operations involving a hovering aircraft and an officer dangling on a rope like a stalled yo-yo.

The Sheriff’s Office also has three deputies assigned to the coast—at points north, central, and south. All three live in their assignment areas, turning their homes into de facto substations, and allowing them to develop an understanding of both the people who live around them, and the vagaries of the coast.

Henry 1 pilots often fly in conditions that would ground other pilots. They’re also trained in longline rescues, those made-for-tv operations involving a hovering aircraft and an officer dangling on a rope like a stalled yo-yo.

“They’re witnessing the rapidly changing power of the ocean—and the cliffs and coastal line, and how it’s always changing,” Dillion says. “They’re seeing the flow of people in and out on the weekend, and how the weather plays a role. If something goes wrong, we have people who have been there.”

State Parks plays a huge role, too. They have one lifeguard tower, at Goat Rock, though it’s rarely staffed outside of holiday weekends, Murphy says. Most of the time, State Park rangers not busy elsewhere cruise along Highway 1 or on one of the three beaches they’re permitted to drive—Salmon Creek, Goat Rock and Wrights. The others are too rocky and impassable.

A lot of the public safety net at the coast could best be defined as saving us from ourselves. No one begrudges anyone from visiting. On the contrary, the emergency workers share the compulsion to breathe in a little salt air on a hot summer day. But man, can a rescuer get a little help?

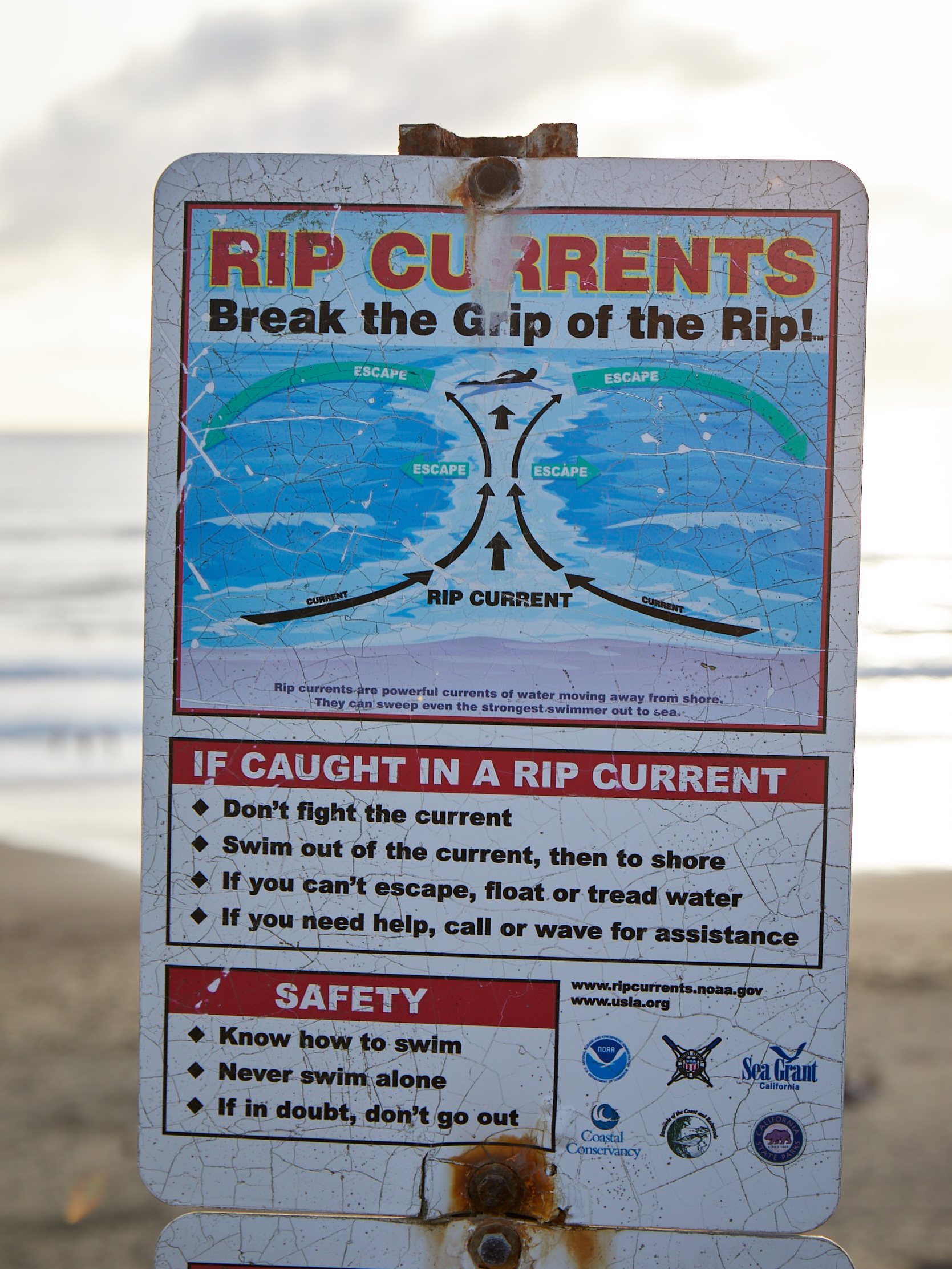

If you’re going out in a canoe, maybe tell your family, Murphy says. Read the signs at the beach; they may be telling you about rip currents or the absence of lifeguards. Spend a minute on the National Weather Service’s website or on windy.com before you set sail.

“Even on a calm day, I really caution people not to turn their back to the ocean,” Murphy says. “I know you can take lot of scenic pictures that way, but if you have a large groundswell, you won’t see it when that powerful water rushes up the beach. That’s probably most of our rescues out here.”

Hearing these stories can make you wonder: Why would anyone sign up to do this work? Stretched-tight resources…traffic hazards…terrain that fights you in a hundred different ways…stupid human tricks, performed daily. It must be the worst job in America.

Except these on-call heroes will tell you it’s the best. Herzberg, long before he was an assistant fire chief, was a lawyer. In that job, he says, he frequently brought chaos to peace. Now he brings peace to chaos, a role he cherishes even at 78 years old. And let’s face it, the outdoor “office” where these first responders labor each day probably has a better view than yours.

“It’s still a beautiful place to work,” Murphy says. “On a bad day, depending on what the circumstances are, just going outside and collecting your thoughts, and seeing the beautiful Sonoma Coast can give you some perspective.”

Common coastal calamities — and how to avoid them

Sneaker waves

The cautionary tale: On September 21, 2021, a large wave swept a 28-year-old woman onto the rocks at Goat Rock Beach. She injured her ribs and head, and was airlifted to a Santa Rosa hospital.

Don’t let it happen to you: Large swells can come out of nowhere. You can’t see the monster coming if your back is turned.

Unstable cliffs

The cautionary tale: On July 27, 2019, a man tumbled over a cliff while hiking near Coleman Beach, sustaining severe facial injuries.

Don’t let it happen to you: The rugged Sonoma coastline was formed by erosion. Stay a few feet from the edge, and you won’t become part of the scenery.

Shark attacks

The cautionary tale: While surfing off North Salmon Creek Beach on October 3, 2021, 38-year-old Eric Steinley felt something clamp down on his leg and drag him underwater. He fought off the shark but wound up with a severed nerve that required several surgeries.

Don’t let it happen to you: Despite the terror they evoke, shark attacks remain rare. That said, it’s always a good idea to swim or surf with others nearby.

Rough seas, strong currents

The cautionary tale: Tragedy struck three boaters, including a child, on July 31, 2021, when their 10-foot aluminum skiff overturned in choppy seas near Salt Point. One adult drowned.

Don’t let it happen to you: Know the ocean currents, check the weather, and make sure you have the experience—and the equipment— for the job.