They appear to sail like boats on an ocean of air. Yet traditional Japanese pole houses are so firmly anchored in the ground that they have withstood centuries of floods, earthquakes and savage winds and multiple generations of use.

These rustic, open-timbered homes, whose architecture dates to the high culture of 16th-century feudal Japan, have a practical and timeless appeal that makes them a fit for the casual Northern California lifestyle that celebrates the outdoors and natural materials.

“Our only regret is that we didn’t do this 15 or 20 years earlier,” said Fredric Frye, who lives with his wife, Brucye, in a pole house they built a dozen years ago on a farm between Cloverdale and Yorkville, near the border of Sonoma and Mendocino counties.

“Our only regret is that we didn’t do this 15 or 20 years earlier,” said Fredric Frye, who lives with his wife, Brucye, in a pole house they built a dozen years ago on a farm between Cloverdale and Yorkville, near the border of Sonoma and Mendocino counties.

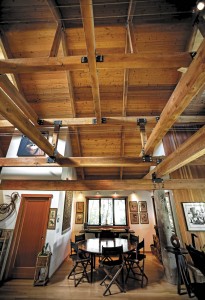

It is a house, he said, that is exceptionally smart in its simplicity, with soaring 24-foot spruce ceilings under a hipped roof and a floor plan so open that only the guest bathroom is completely enclosed. That means that everywhere you go within the house, you can look up in awe at those golden timbers.

The center of the home is the great room, an open expanse unobstructed by load-bearing walls. Perhaps the best feature, however, is the grand engawa — sliding pocket doors that open completely to a covered wraparound veranda where the samurai of the house — in this case Fred Frye — can regard the vast sweep of the landscape and declare it all good.

Although early 20th-century California architects Green & Green and Frank Lloyd Wright were inspired by ancient Japanese architecture, it was the late Gordon Steen of Southern California who brought pole houses to the U.S. in a more commercially visible way, starting in the 1970s. Several of his “Japanese folk homes” are tucked away in Mendocino County, including the Fryes’ home and one built for Pulitzer Prize-winning author Alice Walker.

Now the man who milled the lumber and provided the timbers for some of those homes, including the Frye compound, is carrying on Steen’s vision, but with his own designs and ethos.

Gordon Martin’s Sonoma Pole Houses are completely milled in Healdsburg and shipped in kits complete with hardware, roofing and windows. Instructions for assembly also are included, although all but the most skilled do-it-yourselfers are advised to hire a contractor to set them up properly.

Martin was inspired by Bay Area architect Michelle Kaufmann, who 10 years ago pioneered a new era of high-quality, factory-built homes.

The elegant post-and-beam joinery of his pole houses is stronger than conventional stick framing, said Martin, whose company for years has milled the materials for industrial cooling towers around the world. His Sonoma Millworks in Healdsburg also does re-milling of fine salvaged wood. Among his projects was salvaging and re-milling some 25,000 board feet of old-growth redwood that became part of the new Boudin SF bakery in Santa Rosa’s Montgomery Village shopping center.

Pole houses like the Fryes’ typically are built on heavy poles inserted into the ground. While some people choose not to bury the poles out of concern for rot, Martin maintains that by pressure-treating and encasing the formidable Douglas fir poles in concrete, they can remain safe and sturdy for generations.

Pole houses like the Fryes’ typically are built on heavy poles inserted into the ground. While some people choose not to bury the poles out of concern for rot, Martin maintains that by pressure-treating and encasing the formidable Douglas fir poles in concrete, they can remain safe and sturdy for generations.

With the structural framework anchored so deep in the ground, the building is able to move separately, Martin said, and absorb tremors without breaking. With the living level set so high off the ground, the homes are protected from floods, rot and vermin.

The style felt natural for the Fryes, who made several trips to Japan and were enchanted by Kyoto, a jewel of ancient Japanese architecture. The couple for a number of years lived in a Japanese-style home in Davis, where Fred, a former cancer researcher and comparative pathologist who is regarded as an international expert in reptiles, served on the faculty of the University of California.

He admits his affinity for Asian culture began simply out of necessity.

“When I first got married, Brucye and I didn’t have much money,” he said. “I was going to school on the GI bill. One of the least expensive ways to survive was an Asian diet.”

As they moved up, they began collecting Japanese and Chinese art, a lifetime of treasures that grace the 1,200-square-foot home, a mirror image of their son Erik’s larger, 2,000-square-foot pole house set within what amounts to a family compound.

Together, the Fryes work a farm they call La Primavera, raising chickens and maintaining orchards of antique apples, pears, apricots, peaches, plums and nectarines.

Sonoma Millworks’ Martin has worked on pole houses in Calistoga and Hawaii. But the acquisition of a German-made, computer-operated joinery machine called a Hundegger, which takes up an entire warehouse, now allows him to produce easily and with extreme precision the components for pole-house kits.

The house can be designed in the traditional architect’s CAD software. The Hundegger reads the plans from a flash drive and makes all the adjustments to automatically cut large pieces of wood robotically. The pole houses are available in three sizes: 12 by 12 feet for use as a bonus room or guest quarters, 16 by 16 feet, and 32 by 32 feet. They can be used modularly to make a larger residential cluster and start at about $80,000 for the smallest, most basic kit. That doesn’t include construction or interior finish work.

Ilene Paul first laid eyes on a Japanese country-style building at the Spirit Rock Meditation Center in Marin County. She was so taken by it, with its big overhanging roof and wraparound decks, that she began searching for a way to build one as her own personal retreat.

She and her husband, Don, a contractor, had the perfect piece of land waiting, spectacularly situated above Jenner, looking out at the ocean and some 5,600 protected acres of the Jenner Headlands.

“It’s a world-class location,” Ilene said. “We decided it deserved a world-class house.”

She found a company in Oregon that at the time was selling pole-house kits. Hauling 15 giant poles up the dirt road to their property was so precarious that one trucker refused to go up. Don wound up pulling the big rig up the hill with his little tractor.

It took five weeks to get the foundation in. The couple chose to set the poles deep — three rows of five poles, set 16 feet apart. In process, it looked, Ilene said, a little like Stonehenge.

When finished, the house was 2,800 square feet of living space beneath 22-foot ceilings held up by rough-hewn poles so large that the Pauls can barely put their arms around them. A dramatic open bridge with copper-tube railings leads from a master suite to a second bedroom to Ilene’s

artist’s studio on the “second floor.” Materials are warm and earthy, from the hickory floors to the clay walls.

“There is a Japanese term, wabi-sabi, and it means rustic elegance. The house is not glitzy and shiny, but we consider it has rustic elegance,” explained Ilene, who added Japanese elements such as a stained-glass door she made, inspired by Japanese brush strokes, Asian art and shoji screens.

She described the interior as akin to a temple, a place of “deep peace and calm.”

To Martin, there is something both protective and primal about being in one of these serene homes anchored into the earth and with roofs reaching to the skies.

“It feels like leaving the earth,” he explained. “You are out on the veranda, yet feel protected by the overhang. But when you step inside and look up, you feel exalted.”