You blinked and now the Gravenstein is gone. Already harvested, processed, and celebrated with a glorious town fair, consumed in pies, fritters, ciders, and sauces.

It seems like just the other day banners went up in downtown Sebastopol: “Gravensteins Are Coming.” The annual reminders, hung by Slow Food Russian River revivalists, were quickly replaced by “Gravensteins Are Here” banners.

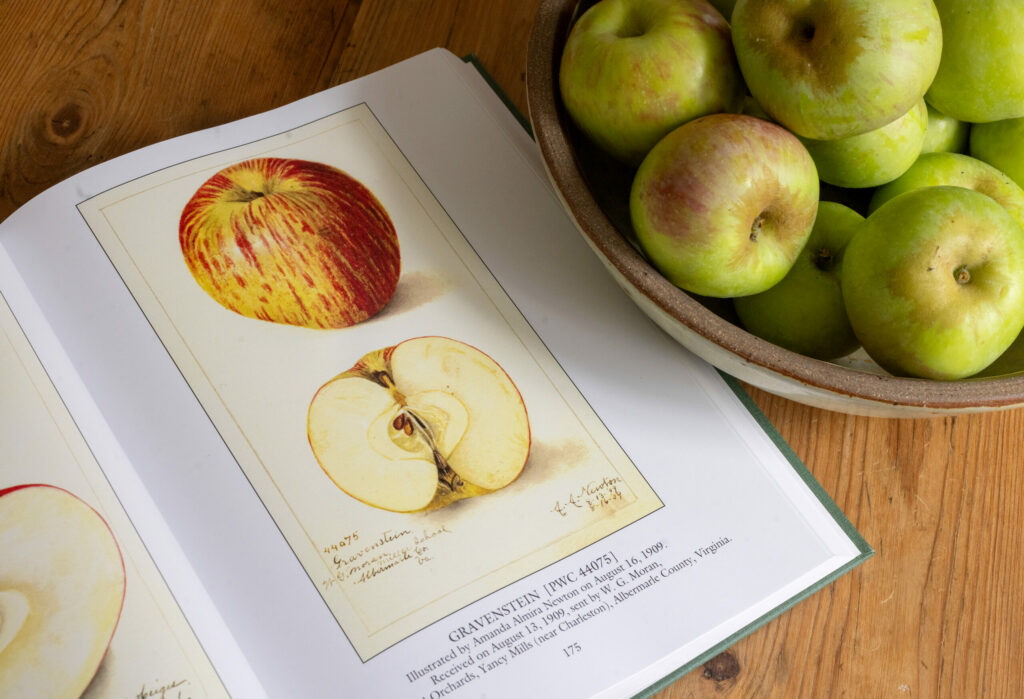

It’s the reason Luther Burbank once said, “If the Gravenstein could be had throughout the year, no other apple need be grown.”

So it goes with the early ripeners, the messy harbingers of a new season that drop around a third of their fruit before harvest. Their window is short. They don’t last long on the counter. It’s why they never made it as a market fresh apple.

Another way of looking at it: “If an apple were a rainbow, it would be a Gravenstein. It’s there, it’s beautiful, and then it’s gone.” That’s how Sebastopol apple grower Dan Lehrer describes it.

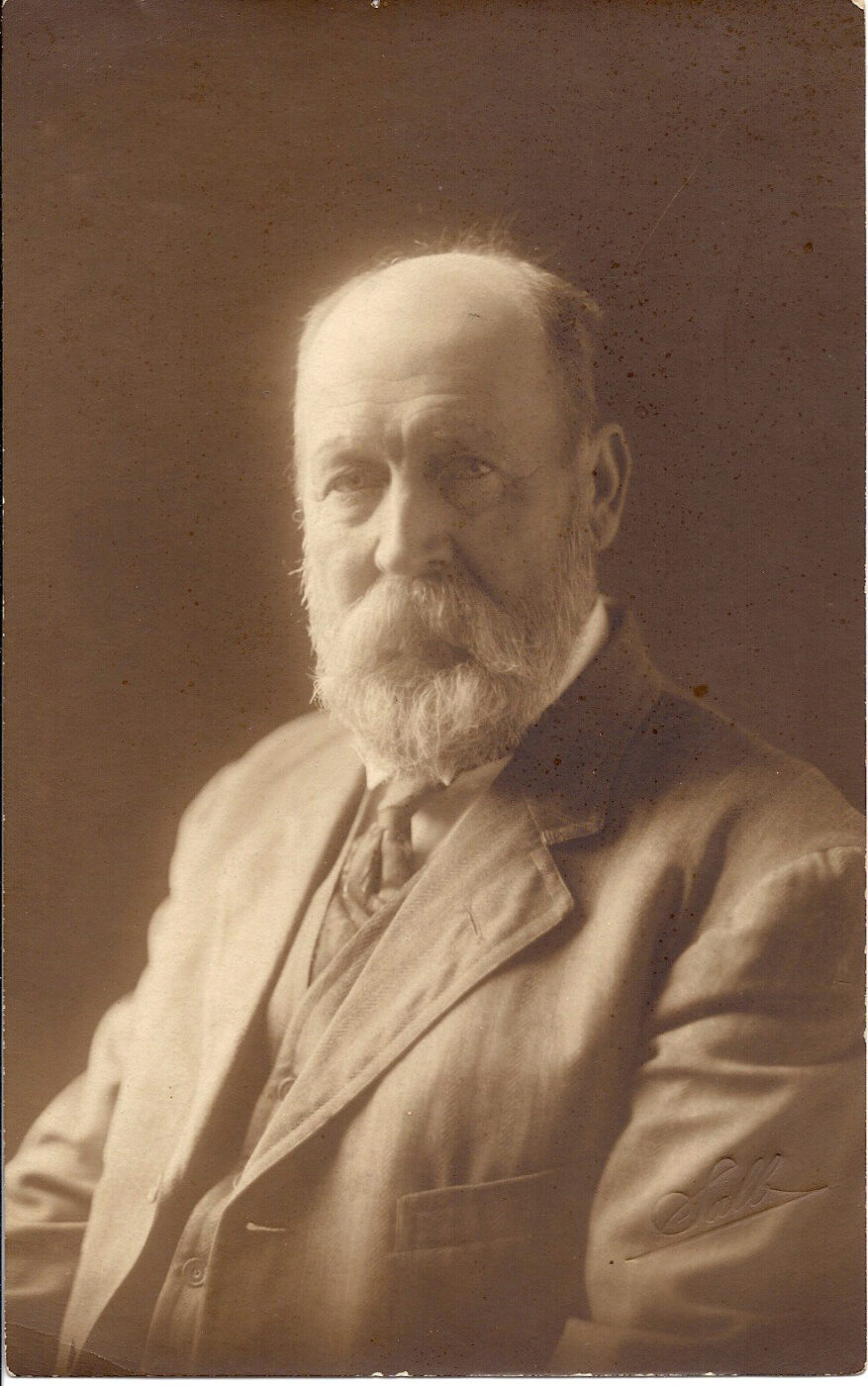

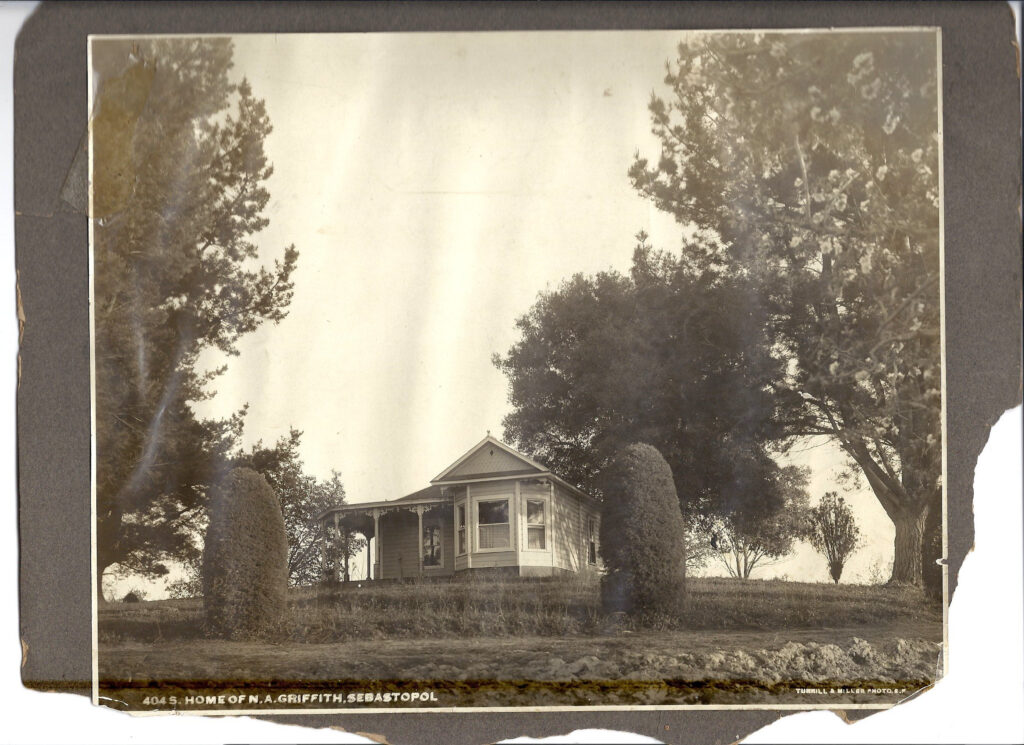

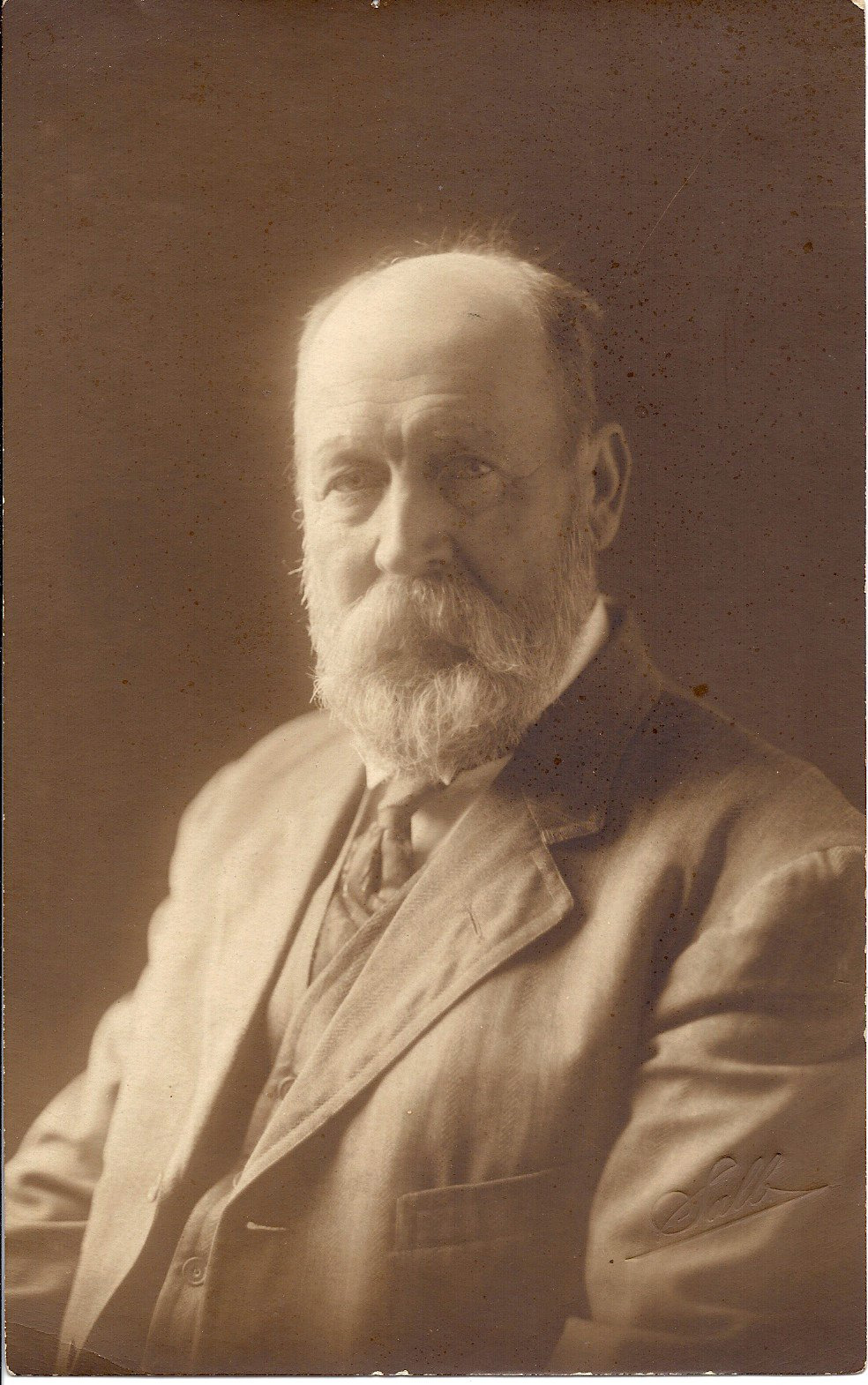

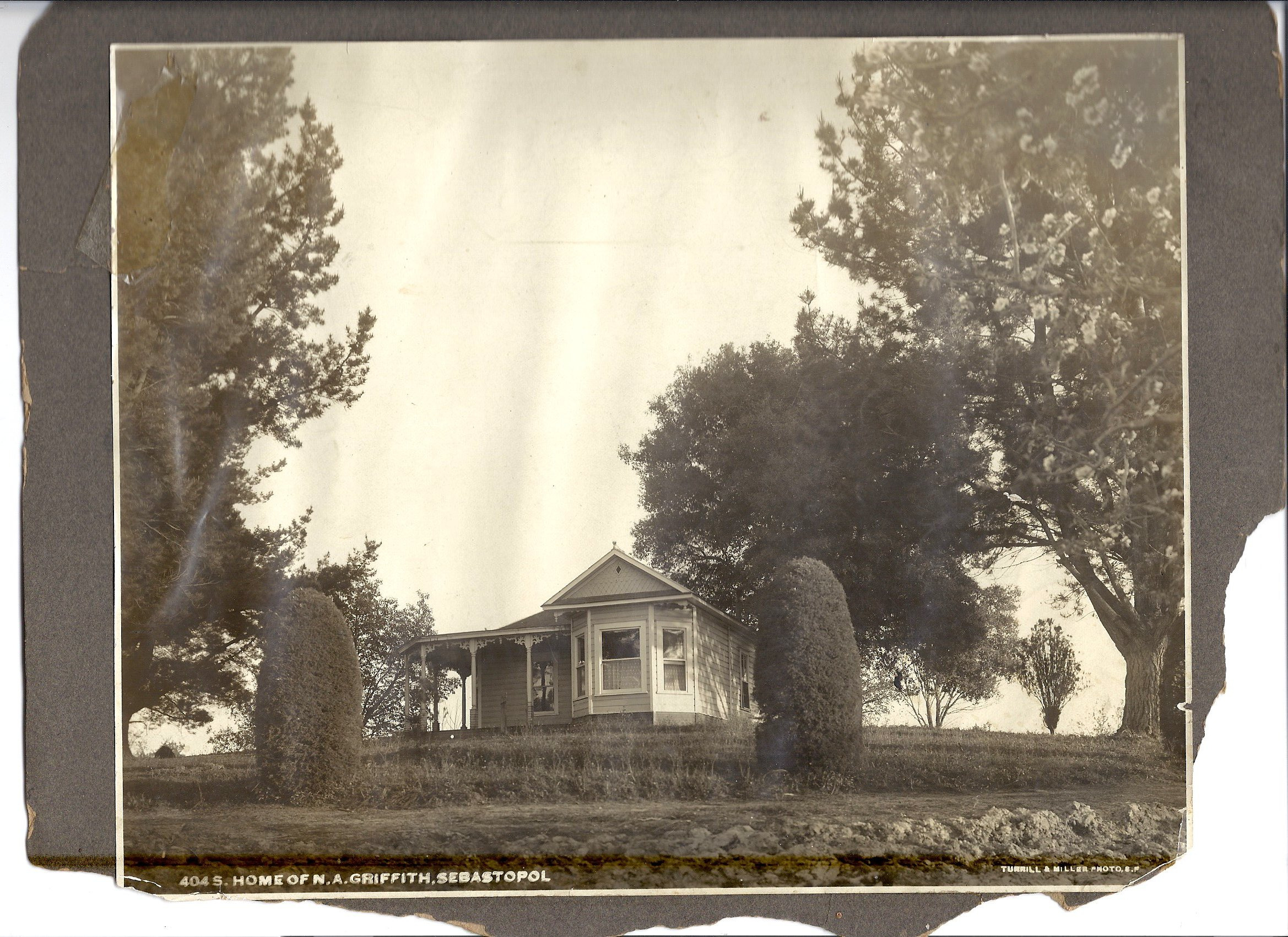

But however fleeting it may be, the Gravenstein is still ours. In Sonoma County, we are very possessive and protective of the Grav. It’s not just the inspiration for the annual Gravenstein Apple Fair, and the namesake of a winding highway and elementary school — it’s a touchstone to another era, well before 1910, when people lined up around the block for the first “Gravenstein Apple Show” under a tent, when our “Grandfather of the Gravenstein” Nathaniel Griffith planted his orchard in 1883 off Laguna Road.

But what if there was another apple out there parading as a Gravenstein? Or maybe a mix-up at birth back in the 17th century, possibly at a royal garden in Denmark. What if there were two very different apples propagating around the world as Gravensteins? It begs the question: Which one is the imposter?

Don’t be alarmed. At this point, it’s only a theory (or scientifically, a hypothesis). One that started in the summer of 2009 as a curious Lehrer strolled the stalls of a Portland farmers market. Whenever he’s traveling, he always checks out the apples for sale.

“There was a guy selling Gravensteins and it was a totally different apple,” he remembers.

Having eaten “thousands” of Gravensteins over the years, Lehrer told the market seller, “That’s not a Gravenstein. And he’s like, ‘Yeah it is.’ I said, ‘No, it’s not.’ And he said, ‘Yeah, it is.’”

So it went, back and forth. Lehrer took a closer look. The most obvious clue was that “it was oblong and very blocky,” he remembers, in contrast to the more squat, round Gravenstein apple that grows in Sonoma County.

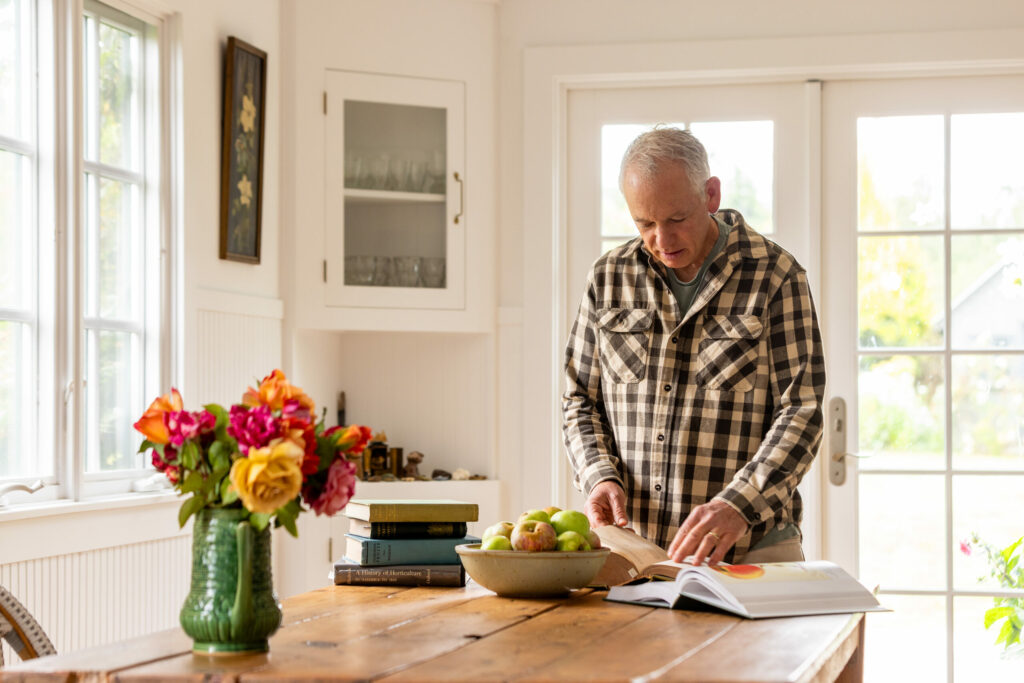

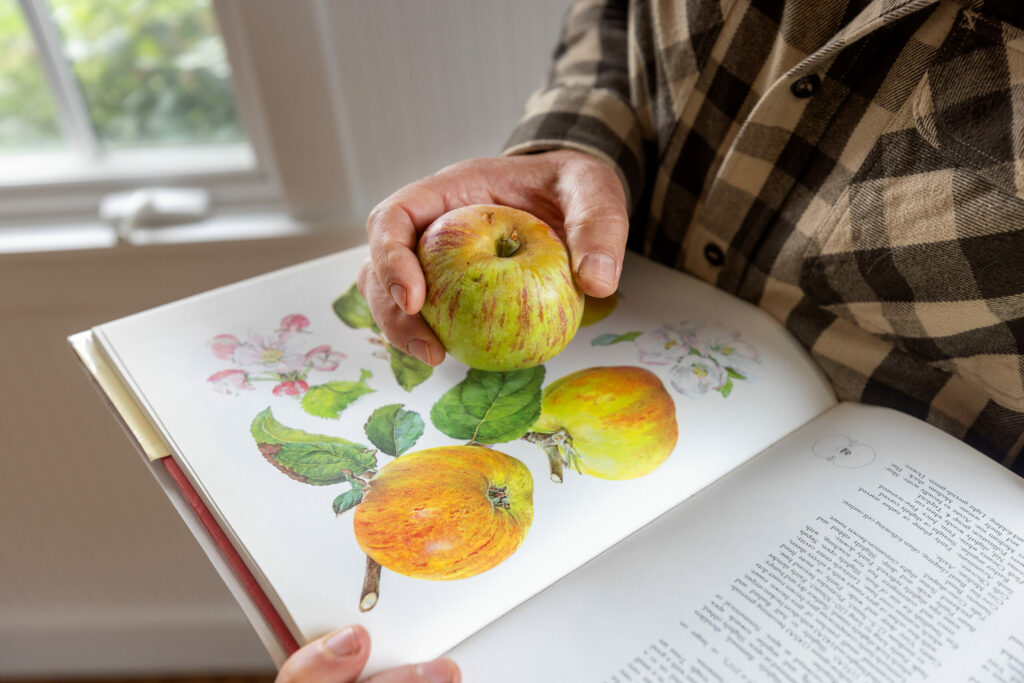

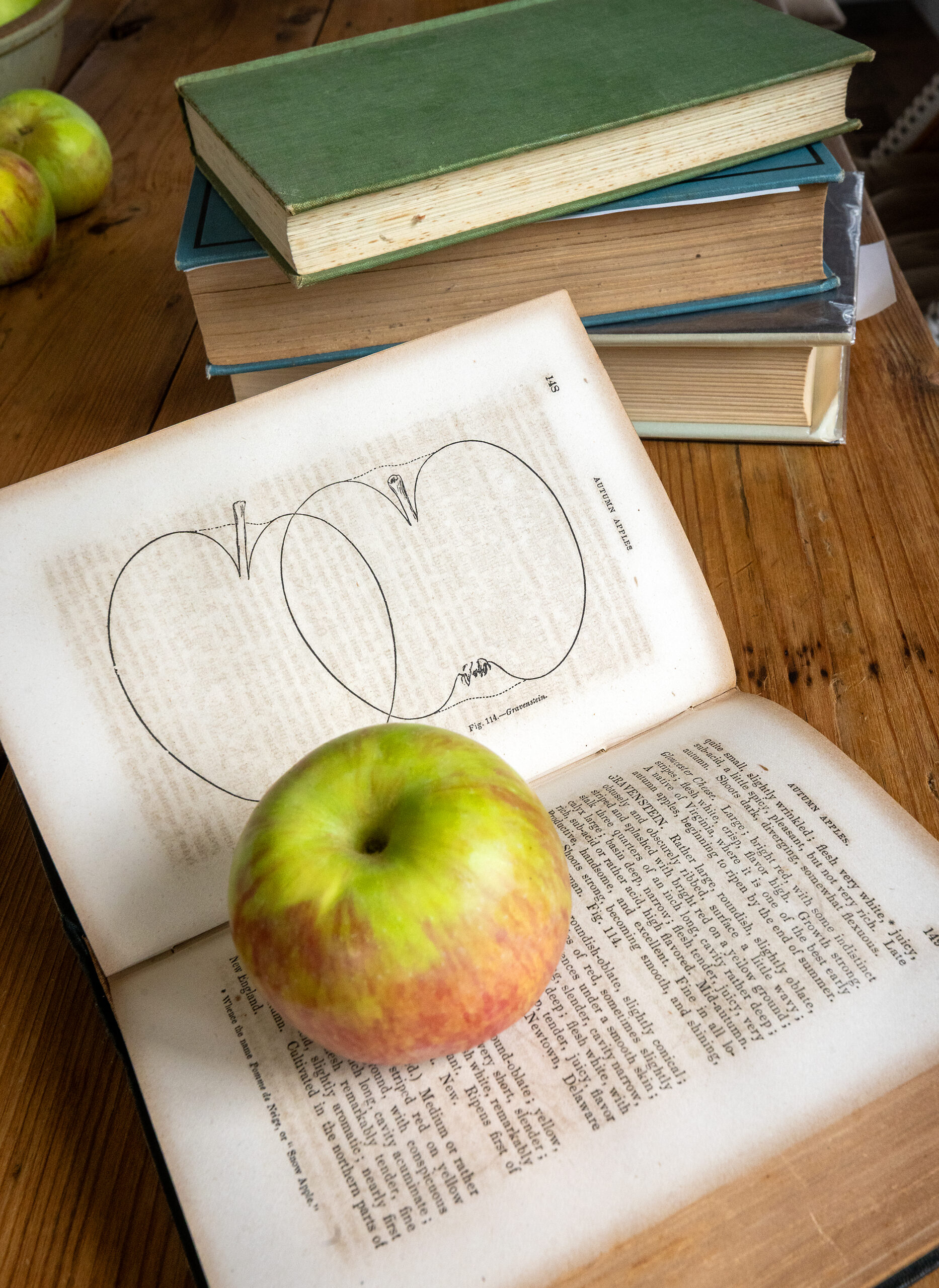

It got him thinking. Although apples are known to produce genetic mutations called “sports” and vary some depending on climate and location, why would there be two such distinctly different Gravensteins? Back home at his 22-acre orchard, where he and his wife, Joanne Krueger, make award-winning apple cider vinegar and other delectables as part of their business, Little Apple Treats, Lehrer spread out his collection of antiquarian apple books on the dining room table. A journalism major at UC Berkeley, he loves a good research project.

He flipped through Edward Wickson’s 1926 book “California Fruits and How to Grow Them,” seeing a description of the Gravenstein as “large, rather flattened.” Other books seemed to concur. But in “The Apple Book,” British apple historian Rosanne Sanders describes the Gravenstein as “oblong, well pronounced ribs running from base to apex” and “rather five-crowned at apex.” Looking at an accompanying drawing, Lehrer says, “This was the apple I saw in Portland.”

Slow Food International, the global grassroots organization promoting sustainable local food systems and traditional foods, with chapters all over the world, has added the Gravenstein to its Ark of Taste, a catalog of “endangered heritage foods.” On its website, there are pages devoted to two different strains of Gravensteins — the Nova Scotia Gravenstein and the Sebastopol Gravenstein.

Paula Shatkin and Carole Flaherty, cheerleaders for the Gravenstein at Slow Food Russian River, said they were not aware of the Nova Scotia version, both admitting they were much more interested in raising awareness about the Gravenstein’s steady decline than distinguishing between variations. They’re more worried about Manzana Products Co. pulling up stakes and leaving town next year, taking with it the last large-scale apple processing plant in the region, and bidding a final farewell to the days when Gravenstein was king.

According to Slow Food International, in Nova Scotia the green versions are often called “Old-Fashioned Gravensteins” to distinguish them from newer red strains, sometimes called Banks Gravensteins and Crimson Gravensteins. Aside from color descriptions, Slow Food doesn’t detail other physical characteristics — particularly shape and size — of the two different types of Gravensteins. But Michelle Cortens, fruit tree expert at Perennia Food and Agriculture in Kentville, Nova Scotia, said the Gravensteins typically found in Nova Scotia are “definitely a rounder squat apple and not oblong.”

The Gravenstein origin story has meandered over the years, but one of the most cited versions is that it was discovered in the garden of the Duke of Augustenberg’s Grasten (“Gravenstein” in German) Palace in mid-1600s Germany, what is now southern Denmark. One of the earliest known descriptions of the Gravenstein is by German academic Christian C.L. Hirschfeld, who wrote that the apple may have originated in Italy, under the name Ville Blanc.

Hirschfeld also wrote about an avid apple grower on a nearby island, Peter Vothmann, whose son, Hans Peter, apprenticed in the garden at Grasten. In researching the history of the Gravenstein, Darlene Hayes, Sebastopol author of “Apple Tales: Stories from the Orchard,” dug up writings by Nicolai Vothmann, son of Hans Peter, who described how apples in his nursery, descendants from the original Gravenstein estate, had begun to change over the years, possibly due to mutations. “In my garden there are still two mother trees, around 60 years old, which my father threaded and planted himself from the mother trees mentioned earlier in Gravenstein’s garden, the most beautiful fruits in their youth, bright yellow, only a little on the sunny side reddish, ribbed and elongated in shape. Now these patriarchs bear nothing but round fruits, heavily shaded with red, which are also noticeably tougher in their flesh than they were.”

It seems he witnessed the variability that Lehrer saw in Portland — in effect starting with a yellow-green oblong shape, then mutating years later into a rounder, redder sport, something like the red Gravenstein we know today.

So how did both types arrive on the West Coast with one more prominent in Oregon and the other dominant in Sonoma County? Over the years, it has been widely reported by local historians and apple growers that Sonoma County’s Gravenstein likely descended from trees first planted by Russian settlers at Fort Ross as early as 1812. One possible scenario is that after the Gravenstein first sprouted in what is Denmark today, word spread about its sweet-tart flavor as a delicious source for pies and ciders, it began popping up at different markets in Europe — and mutations of the apple took root in different regions. One redder, rounder strain might have migrated eastward into Russia and landed at Fort Ross, where it became the Sebastopol Gravenstein.

Meanwhile, around the same time, another Gravenstein sport from Denmark traveled westward, through England and to the Northeastern United States.

So how did the East Coast or Nova Scotia version, that Lehrer might have seen in Portland, wind up in Oregon? Most likely the Oregon Trail. Jeannie Berg, former owner of Queener Farms in Scio, Oregon, just east of Willamette Valley, shared several pages of research she did at the Oregon Historical Society, showing that pioneer farmer Henderson Luelling brought Gravenstein trees to Oregon in his “Traveling Nursery” in 1847.

Sebastopol apple grower Stan Devoto has seen variations beyond what he calls “the standard Gravenstein,” which is green with red stripes, and the red Gravenstein, with a more solid red color, often ripening a little earlier. There’s the Rosebrook Gravenstein (that looks like the standard but with more stripes), ripening a week later than both. Devoto also has a friend who grafted a sport that ripens later in September and named it the Bonner Gravenstein.

But more interesting is a late-ripening Gravenstein that his neighbor Randy Roberts grows. It looks almost like a red delicious with points at the bottom, he says. “And gosh darn, it tastes like a Jonagold.”

Conversations with Oregon growers confirm the wide range of Gravenstein variability in the Pacific Northwest. “The vast majority of our Gravensteins end up having more of a squarish shape to them, with kind of straight sides and a little bit taller,” says Christina Fordyce, current owner of Queener Farms. They call the green ones “traditional Gravensteins.” They’re “a little more tart” and ripen just before the red Gravensteins.

“It wouldn’t surprise me at all if some of the Gravensteins that people have up here in the Pacific Northwest do taste different or look different than the ones that are so famous down in Sonoma, because of climate differences and growing conditions, and the genetic mutations that happen over the decades,” Fordyce says.

Third-generation apple grower Randy Kiyokawa, owner of Kiyokawa Family Orchards in Parkdale, Oregon, says he sells both green and red Gravenstein varieties at farmer’s markets around the state, including several in Portland, possibly where Lehrer first encountered the suspect Gravenstein. Kiyokawa has seen tall ones and smaller round ones. They tend to vary, he says. “Let me know if you find out we don’t have Gravensteins,” he says with a laugh, offering to send a few samples in the mail. “We might have to rename them.”

At this point, DNA fingerprinting might be the only way to solve the mystery. But fully mapping the DNA of a Gravenstein apple is tricky because it’s a triploid variety, which basically means it has three sets of chromosomes, unlike many other diploid apples with two sets of chromosomes like humans, says Rachel Spaeth, a Santa Rosa research horticulturist who studies the genetic makeup of rare fruits.

Her best guess? “I would say the Gravenstein was probably bred in Germany, or somewhere in the middle of Europe, and then it probably went off in two different directions, as somebody got a seedling or a bud sport. And it’s really interesting that it made it around the globe two different ways, and then connected on the West Coast. I think they’re probably two different apples, but maybe they share parentage.”

Fortunately, many Gravensteins throughout the West Coast have already been genetically fingerprinted at the Washington Tree Fruit Genotyping Laboratory, which receives test samples from the public at MyFruitTree.org. Cameron Peace, Washington State University professor of fruit tree genetics, has tested multiple trees from northern California and western Washington and Oregon and he says they all have “the usual Gravenstein DNA profile.”

He has not tested Gravensteins from Nova Scotia, but believes the Sonoma County Gravenstein is a sport commonly known as red Gravenstein. His guess is that the observed differences are “phenotypic differences among sports,” referring to the effects of the environment, like soil and climate, noting that DNA technology can’t differentiate among sports of a cultivar because they produce the same DNA profile.

Digging deeper would likely require whole genome sequencing, which Spaeth says, “would elucidate differences, but the price point difference might be prohibitive.”

In the meantime, “at least people are talking about Gravensteins,” says Carole Flaherty, who tends around 200 apple trees, including several “beautiful red Gravensteins” planted in 1915. She also leads Slow Food Russian River’s Save Our Orchards project. “People need to know what danger our orchards are in.” That applies to all Gravensteins, she says, whether green or red or candy-striped, whether short and squat or tall and “squarish,” whether ribbed with shoulders or no shoulders at all.

But Lehrer remains intrigued, still sleuthing in the archives, looking forward to the next time he spots another bizarro Gravenstein. “The mystery is like a set of Russian nesting dolls,” he says. “Open one and another appears inside.”