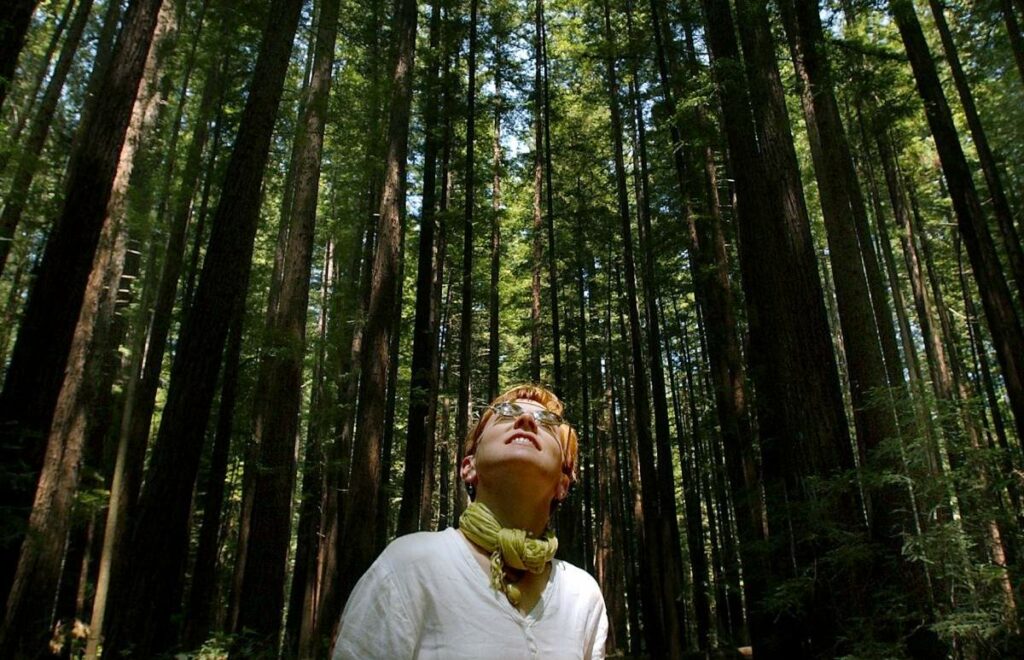

Coast Redwoods love the water — the more, the better, it seems. They love soupy fog so thick it hangs like mist. They love rain that rushes off ridgelines in seasonal rivulets. And they especially love creeks and rivers that overrun their banks to flood flat valley floors, submerging the feet of the world’s tallest trees.

Foggy weather, plenty of rain, a broad-banked river that regularly floods? Check, check and check — Sonoma has a place like that.

“The Russian River was once coated with beautiful virgin redwood stands,” says Brendan O’Neil, an environmental scientist and Chief of Natural Resources for California State Parks’ Sonoma-Mendocino District. “The most famous of all was called the Big Bottom stands, in Guerneville. That area, because it’s so prone to flooding, ended up growing some of the finest redwoods in all of California.”

The name Big Bottom stuck (it refers to the alluvial floodplain upon which the town sits), but most of the massive trees are long gone, having been logged in the late 1800s and early 1900s, many destined for cigar boxes.

Not only do they appreciate a good soaking, but creekside groves also benefit from the loads of nutrient-rich sediment deposited by floodwaters. “If you look at the trunks of a lot of the giants in Mendocino and Humboldt counties, you see that they lack that taper that you generally see,” O’Neil says. “That’s because they have been buried so many times.”

Redwoods respond by sending out a whole new root system to tap into the fresh topsoil and, even more critically, by producing seeds: a relatively rare occurrence for the species, with fire being the only other trigger.

All redwoods, no matter where, react positively and immediately to water availability in the winter. “You can see trees start to swell when it rains. They store a lot of water in their bark and canopy. They’re essentially huge water pumps,” O’Neil says.

But these botanical marvels don’t only take; they also give. Their gravity-defying canopies are home to an entire ecosystem of living things, including other plants, fairy shrimp, salamanders and flying squirrels. In death, redwoods offer valuable habitat as well, and if they are so fortunate as to fall into a nearby waterway, they can provide hiding spots for spawning salmon.

Survivors of the logging boom face a new set of threats today, and predictably many relate to fog levels, rainfall patterns and river flows — natural factors that humans have interrupted through climate change, dams and other alterations to hydrologic regimes, O’Neil says.

“Not to sign off with a story of woe, but it’s something to think about: all the beautiful things we have in this world, and the challenges we face in how we manage them.”