This article was published in the Nov/Dec 2018 issue of Sonoma Magazine.

Editors note: On Wednesday, January 9, 2019, DNA testing confirmed that the partial human remains found on a Mendocino County beach in May, 2018, belong to 16-year-old Hannah Hart, who was killed nine months ago when a van driven by one of her adoptive mothers and carrying her family of eight plunged off a seaside cliff.

The girl who shook Dana DeKalb from her deep sleep came from the blue house next door, but Dana had never laid eyes on her. It was 1:30 a.m. in late August 2017. The girl was small, black, and wrapped in a bramble-covered blanket. Her two front teeth were missing. Her name was Hannah, and she begged Dana to hide and protect her.

Dana’s husband, Bruce, had answered the door and listened in astonishment as the girl wailed about her “racist” and “abusive” mothers. She had then dashed up the stairs to the bedroom, leaving him speechless in the doorway. As Dana rose from her bed and lowered her feet to the floor, she processed the little she knew about Hannah and her family.

Three months earlier, a realtor named Joe Carbajal had introduced himself to Dana in the sloping gravel driveway that cuts through the DeKalbs’ 2.5-acre property in Woodland, Washington, a forested town 30 miles north of Portland. He said new neighbors were moving in next door, a family with “lots of kids” and animals. Dana, 58 and retired, found this news heartening. She and Bruce hoped the family, owners instead of renters for once, would buck the trend of unpleasant neighbors they’d dealt with over their 21 years in Woodland. But after the move-in date, weeks passed without so much as a yell from next door. Eventually Bruce saw two boys — two black boys — taking out the garbage, but no others, and no animals. The DeKalbs questioned whether the rest of the family really existed.

Dana finally met the parents in July, as she was raking gravel at the fork in the properties’ shared driveway. A GMC Yukon rolled down from the house, and a woman, “super bubbly and friendly,” recalls Dana, jumped from the passenger side and introduced herself as Sarah. The woman in the driver’s seat, Sarah said, was Jen, her wife. The car was deep and its windows tinted, so Dana couldn’t see into the back, and for another month, she and Bruce maintained their impression: Two white women. Two black children. Friendly, but reserved.

Hannah’s early morning visit in August quickly distorted that image. Now, over a year later, Dana is haunted by her failure to call the police or child welfare authorities immediately following the incident.

When she finally did call Child Protective Services seven months later, the family reacted swiftly. On March 23, 2018, after a series of imploring visits from one of the boys, 15-year-old Devonte, Dana alerted authorities. The next day, the Yukon tore out of the driveway. Two days later it was found flattened below the sheer drop of a 100-foot cliff off Highway 1 in Mendocino County, a journey of over 500 miles from the family’s Washington home.

First responders pulled the bodies of Jennifer Hart from the driver’s seat and Sarah Hart from the back, and those of three of their children — Markis, 19, and Jeremiah and Abigail, both 14—from the surf. Two weeks later, the body of the youngest, 12-year-old Ciera, washed up on the beach, and 16-year-old Hannah and Devonte, though still missing, were presumed dead. By that point, it was clear that the crash was intentional. Jennifer had driven herself, her wife, and her six adopted children off the cliff on purpose.

MENDOCINO: 2018

The SUV fell from a cliff whose view of the ocean, were it not for the fog, would be endless. Roadtrippers frequently stop at the turnout — 20 miles north of Fort Bragg — to take photographs. Then they resume their drive. North or south, they must contend with a roadway characterized by narrow lanes and blind corners. It might have been easy to judge another family, under different circumstances, victims of the road. But with the Harts, emerging information suggested otherwise.

At around 4:30 p.m. on Wednesday, March 28, Mendocino Sheriff Tom Allman took the podium outside the California Highway Patrol’s cinderblock offices in Ukiah to brief reporters and, through a live Facebook feed, the public. He spoke quickly and conversationally as he named the victims and the missing children, summarized the search being conducted by land, air, and water, and gave shout-outs to the agencies and teams collaborating in the investigation.

Before taking questions, Allman tried to explain what he had observed at the crash site. “I was at the scene two days ago. I can tell you, it was a very confusing scene, because there were no skid marks,” he said. “There were no brake marks. There was no indication of why this vehicle traversed approximately over 75 feet off a dirt pullout and went into the Pacific Ocean.”

In the days following that press conference, with help from the CHP and Clark County Sheriff’s Office (whose jurisdiction includes Woodland), Allman’s team continued reconstructing the family’s final road trip. From cellphone pings, surveillance footage from a Safeway, and an eyewitness account, investigators determined the Yukon drove from Woodland to Newport, Oregon, continued south on Highway 101 until reaching Leggett, California, then switched to the coastal and sinuous Highway 1 — where the Harts, on their way south to Fort Bragg, passed the broad turnout they would return to within 36 hours. They reached Fort Bragg at 8 p.m. on March 24, a day after CPS had knocked on their door in Woodland. Two days later, a German tourist spotted the wreck.

The family’s near-miss with CPS in Washington was by no means the first time a child welfare agency had taken interest in the Harts. In fact, in the weeks after the crash, reports from state agencies, police departments, and the family’s former friends sketched a history of neglect and abuse in every state they had lived in: Minnesota, Oregon, and Washington. In Jen and Sarah’s 12 years with the children, most of those reports went unheeded. When authorities did get involved, the couple managed to dissuade police and social workers from removing the children with a well-crafted appearance and accompanying narrative of victimhood.

But the story of the Hart children starts in Texas, where they were born and placed into the foster system. Their adoption records remain sealed, but family members of biological siblings Devonte, Jeremiah, and Ciera have stepped forward. Their account shows that in Texas, as in Minnesota, Oregon, and Washington, the children’s fate was determined by a consistent dynamic. People who had the opportunity to help them were unable or unwilling to think past their assumptions or respond to their nagging suspicions, even at moments when clearer judgment might have delivered the children to safety.

HOUSTON: 2005 – 2010

Like most regular viewers of TV news, Shonda Jones heard about the crash in early spring, when the story captured national headlines. Early reports mentioned one name, Hart, which to Jones, a family law attorney in Houston, meant nothing. But one night weeks later, as she worked late in her downtown office, she saw a televised update announcing the search status and listing the names of the missing and the dead.

“Devonte … Harris County, Texas … Minnesota …”

Devonte.

The name rattled in Jones’ head — she thought immediately of a former client, Priscilla Celestine, and was shaking as she reached for the phone.

Celestine, 67, was the aunt of Devonte, Jeremiah, and Ciera. Briefly in 2006, she had welcomed them and their older brother Dontay into her home, and when the Texas Department of Family and Protective Services took them from her after only four months, she had hired Jones to help her regain custody.

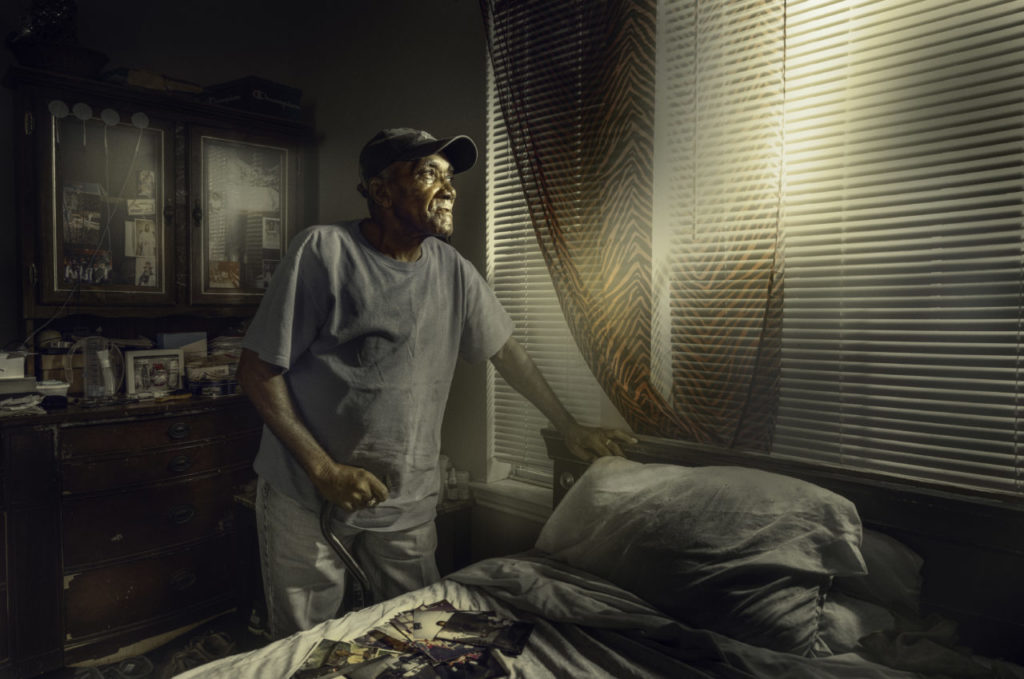

Their mother, Sherry Davis, was addicted to crack cocaine, and had lost custody of the boys when they were infants — in 2002, Devonte’s birth year, and 2004, Jeremiah’s. Both boys had gone to live with Sherry’s husband, Nathaniel Davis. Nathaniel wasn’t their biological father, but he embraced the children nonetheless, diverting a portion of his monthly disability check from a car accident years earlier toward clothing, feeding, and making a home for the children in his South Houston apartment, where he lived alone. But on April 20, 2005, in the delivery room of Houston’s Ben Taub Hospital, two social workers from Texas authorities informed him that his custody had ended. Sherry Davis’ third child, Ciera, had just been born.

Nathaniel is a small man, 76 years old. When he recounts this moment, his voice erupts and he rubs his knee, scarred smooth by five surgeries. “They said that Sherry bossed me, whatever she said would go,” he said. “Since Sherry was on crack cocaine, they said I would let Sherry take over.”

For the next year, Texas child welfare services cycled the young children through foster homes and emergency shelters, and in June 2006 brought them to Celestine, who had agreed to care for them while Sherry’s parental rights were being terminated — which would open the door to adoption without her consent. Jones emphasizes that Celestine had successfully raised a daughter of her own, held a steady job, and had moved into a more spacious home to accommodate the children. She intended to adopt them. In December, a social worker arrived at her home unannounced, and inside she found the children, Celestine’s adult daughter — and Sherry. Celestine had left to take an extra shift at work. The social worker, claiming Celestine had agreed to prohibit Sherry from visiting her kids, removed them on the spot.

The children were returned to foster care, and in 2008, a private adoption agency in Fergus Falls, Minnesota, matched Devonte, Jeremiah, and Ciera with two hopeful parents: Jennifer and Sarah Hart. (Dontay remained in foster care until his 18th birthday in 2014, at which point Nathaniel adopted him.) In the meantime, a crushed but determined Celestine had enlisted Jones, and for the next three and a half years fought to regain custody of her niece and nephews. Jones felt her task, to prove Celestine’s fitness as a parent, was simple, and she’s still baffled by the resistance she met in the process.

As part of her discovery process, Jones asked questions about the home of the prospective parents in Minnesota; any red flags would have supported Celestine’s case. But Belinda Chagnard, the state’s child protective services attorney, objected to each question on the grounds that it “seeks discovery of information that is not relevant to the case.”

During the hearing, attorney Brian Fischer, assigned by Judge Robert Molder to represent the children, painted a misleading picture of the children’s home life in Texas, presenting details in a way that, Jones believes, confused the filthy home of a foster parent with Celestine’s safe and clean one. On the basis of the social worker’s testimony about the unannounced visit, Judge Molder denied the petition, and in 2010, well after Jen and Sarah’s adoption had been finalized, the First District Court of Appeals put the issue to bed: “We see no reason why Celestine should be allowed to have yet another bite at the proverbial apple.”

Fischer declined an interview, and Chagnard did not return multiple calls. Jones, who is black, thinks both were guided by the “automatic assumption” that two progressive white mothers in Minnesota could give these kids a better life than any of their black family members. “Unfortunately,” Jones said, “stereotypes exist, and some blacks live up to, and even exceed that stereotype. … But that’s exactly what you’re trying to prevent. … People, when they really don’t know another group, they just see them as a whole.”

“We’re not stupid,” she added. “We’re not gonna fight to put children with animals.”

When the children went, they vanished — and until this April, their biological family knew nothing about the women who adopted them. They did not know that months after the adoption was finalized in September 2009, the private adoption agency, Permanent Family Resource Center, was cited for violations including failures to conduct adequate home studies. Or that later, in 2012, PFRC was shut down for dozens more such violations. Nor did they know that in September 2008, before the adoption was finalized, and while Celestine was still in court, police in Alexandria, Minnesota, received a call from Woodland Elementary School about 6-year-old Hannah Hart having a bruise on her arm that she told teachers came from being struck by a belt.

“They also have five additional adopted children in the home,” the police report says of Jen and Sarah. “They say Hannah has been constantly going through food issues. … They said they did not know how the bruise would have gotten on her arm, but stated that a few days prior to our interview Hannah had fallen down eight stairs in their house.”

MINNESOTA: 2004 – 2013

Jen and Sarah first met as students in elementary education at Northern State University in Aberdeen, South Dakota. Soon after their relationship began, the couple slowly retreated from friends and family, and began a journey that would take them from Minnesota to Oregon to Washington. In their hometowns in South Dakota — Huron for Jen, and Big Stone City for Sarah — news of the crash was like hearing about ghosts “Most of us have been grieving for the last 17 years,” said Sarah’s mother, Brenda Gengler. “She chose Jen over us, for life.”

According to a child welfare report from Oregon, Jen estranged herself from those who criticized her parenting, and Sarah followed suit. The report, which draws from an anonymous friend’s account, says that Jen stopped speaking to her father, Douglas, and one of her brothers, because of such a disagreement.

Those who speak most highly of Jen and Sarah rely heavily on social media for evidence. In September 2006, after adopting biological siblings Markis, Hannah, and Abigail out of the foster system in Colorado County, Texas, Jen began documenting her life as a full-time parent on Facebook. She had quit her job at Herberger’s, a department store in Alexandria, Minnesota’s Viking Plaza Mall, leaving Sarah, who also worked there, as sole breadwinner. (Thereafter the family lived on Sarah’s income, $2,000 to $2,500 a month in adoption subsidies, and Nathaniel’s child support for Devonte and Jeremiah).

Jen dedicated her new free time to family activities — she announced plans for various road trips (“driving northeast on the great moose adventure,” she wrote) and published snippets of dialogue from her apparently precocious children. Gayle Klinsky, who had employed Jen at her one-hour-photo studio in Huron, recalls wanting to escape into every Hart family photograph. In her dark living room, barefoot and supine on a green La-Z-Boy, Klinsky remembered, “It was like you wanted to move in with her and be part of it. Beautiful, beautiful children.” Jen also lamented, and embellished, the conditions the kids came from. “She was saving these children from really horrible backgrounds,” said Klinsky.

Police reports from Alexandria, Minnesota, where Jen and Sarah lived from 2004 to 2013, suggest that the women trusted and relied on local police as a resource. Between 2004 and 2010, they called 13 times about incidents in which they suspected their neighbor — car break-ins, window peepers, disruptive outdoor parties — and in 2009, police facilitated a detente between the neighbors. They also frequently called about other issues. In 2004, Jen asked for help with a fallen branch that had damaged the side of their house; Sarah made a child welfare report in 2006 about a little girl running around a parking lot without pants. In 2008, Sarah reported that their cat, bought three days prior at the Pet Center in the mall, had died.

But two and a half years before they left Minnesota, the Harts stopped calling altogether. On November 15, 2010, a teacher from Woodland Elementary, where five of the kids were enrolled (Markis had just started middle school), called Douglas County Child Protective Services about a first-grader named Abigail Hart having bruises on her stomach and back, the result of her mother bending her over the bathtub, holding her head under cold water, and hitting her with a closed fist. According to the report, “she had a penny in her pocket … this made her mom mad.”

Detective Larry Dailey and social worker Nancy Wiebe interviewed Abigail and some of her siblings at the school. At the police station, they interviewed Jen and Sarah separately. “They did leave me with the impression that they thought the school was being overreactive and they should be allowed to administer punishment as they saw fit as long as it wasn’t flat-out beating,” the now retired Dailey said. “But bruises on the stomach, that was kind of alarming.”

Abigail said Jen delivered the punishment, but the mothers said otherwise, with Sarah taking the blame. Four days later, Jen wrote in a Facebook post, “Our realtor recently did the first walk through of the house,” explaining that they were planning to sell and move to the West Coast. In December and January, Woodland Elementary called Douglas County CPS three times about similar issues, but stopped “because they didn’t want [the] children being disciplined or punished.” In December, Sarah was charged with domestic assault and malicious punishment of a child; she ultimately pleaded guilty to the first charge and the second was dropped. On April 15, 2011, one day after Sarah had reached her probation agreement, Jen and Sarah pulled all six children from the Alexandria public schools.

OREGON: 2013 – 2017

As a child growing up in the corn-dense, cicada-loud High Plains, Jen had been inspired by a poem her grandmother had written about the Oregon coast, says Nusheen Bakhtiar, a friend of the Harts from Portland. At music festivals in Southern Minnesota’s Harmony Park, Sarah and Jen found kindred spirits in followers of the Portland-based musical collective Nahko and Medicine for the People, and the West began to represent the realization of a dream — a place in which their lifestyle would be encouraged, not just tolerated.

The move created an even more insular world for the six children. They were home-schooled, and there were no more watchful teachers to spot signs of abuse. The new setting also provided an escape from CPS scrutiny, but soon enough the agency was pulled back into the picture. On July 18, 2013, two former friends of the family called the Oregon Department of Human Services. One of them had gone to high school with Jen’s brother, and remains anonymous. The other, Alexandra Argyropoulos, who revealed herself to AP reporters in April, met Jen through Facebook in 2010.

Both Argyropoulos and the other caller described Jen and Sarah’s methods of abuse, which they had witnessed over years of visits with the family. The mothers withheld food from their noticeably undersized children. They subjected them to hours-long, light-deprived “timeouts.” (In an interview with social workers later that summer, Jen described this form of discipline as “meditation.”) The kids were “trained robots,” said Argyropoulos, according to the DHS report. They raised their hands to speak, smiled for staged photos before going “back to looking lifeless,” and waited for Jen’s permission before responding to simple questions. According to the report, Jen acted out of duty. She “views the children as animals,” it reads, “and she as their savior.”

It took 36 days of back-and-forth with Sarah before the agency representatives following up on the report could nail down an interview date. Sarah said Jen and the kids were on a road trip, and sure enough, in an August 2012 Facebook post, Jen described a “sacred moment” from a festival in Tidewater, Oregon, between Devonte and a musician named Xavier Rudd. Fifteen days after the post, two social workers visited the family at home. One interviewed Jen and Sarah together while the other interviewed the children individually. According to the report, Jen and Sarah painted themselves as the victims: “they have been targeted due to being a vegetarian, lesbian couple who married and adopted high-risk, abused children, while living in a small, midwest town.” As for the children, they “provided nearly identical answers to all questions asked” and all but Devonte showed “little emotion or animation.” The children disclosed no abuse or withholding of food, and the social workers marked them as “Safe.”

Before the interviews, DHS learned from a social worker in Minnesota, probably Nancy Wiebe, that “these women look normal” and will almost certainly claim that the children’s backgrounds in Texas explain their food issues. “Without any regular or consistent academic or medical oversight,” the worker added, “these children risk falling through the cracks.” Furthermore, the children appeared small for their ages, with all but Jeremiah falling below their growth charts. But when, per DHS request, a doctor evaluated them in November, she determined them to be healthy.

Social workers in Oregon have the right to implement an in-home safety plan if they believe a family needs extra monitoring; in this case, they did not. The Children’s Center, a nonprofit intervention organization that DHS consults in neglect and abuse cases, declined to see the children after the caseworkers had completed their interviews. It remains unclear why.

Dr. Cathy Lang, who has been with the Children’s Center since 2016 and directs its medical clinic, couldn’t speak about this case specifically due to HIPAA privacy requirements. But she said that when children do not disclose abuse, the center often declines an interview in order to avoid another false negative. In these cases, she said, the center might work with DHS to check in with the children at a later date, when they might feel more comfortable sharing the truth. Without DHS’s monitoring, the center loses its connection to the family.

In January of this year, Oregon Secretary of State Dennis Richardson published a report on the failures of Oregon’s child welfare system. It referred to a 2016 survey that found 57 percent of child welfare workers were overburdened by their caseloads. As a result, they sacrificed quality. “When I first started, I was concerned about not being able to do everything as it should be done,” said one former caseworker. “My supervisor sat me down and told me I couldn’t expect to do consistent ‘A’ level work. ‘C’ is best.”

DHS representatives are not allowed to comment on the Hart case, so all that is known is what can be gleaned from the agency’s 2013 report. “There are some indications of abuse or neglect,” the report says, “but there is insufficient data to conclude … that child abuse or neglect occurred.”

WASHINGTON & CALIFORNIA: 2017 – 2018

Even the most forgiving among those who knew Jen, Sarah, and their children run into a mental wall when confronted with the evidence of abuse and circumstances of the family’s death. The appearance of a happy, harmonious biracial family was so strong that their minds cannot countenance the people portrayed in the media after Jen drove all eight family members to their deaths. The news contradicts what they knew; it can’t be true, and yet they know it to be true. Chelsea Read, who worked with Sarah at a Kohl’s in Beaverton, Oregon, explained it like this: “Even if someone does something terrible and your view is changed on them, you still have to grieve the loss of the person you thought you knew.”

It’s a state so paralyzing that many have refused to keep following the story. They’ve staunched the information flow, fearing it will taint the mourning process. But their rejection of new information perpetuates the old information, much of which Jen and Sarah controlled. As a result, they tell the same stories, such as the pure fabrication that Devonte’s biological parents held a gun to his head, or the half-truth that the kids were home-schooled because Devonte had been bullied at school in Minnesota. Gayle Klinsky, in South Dakota, resisted the news at first, but as word trickled in, “little by little,” she adjusted her perspective.

In contrast the DeKalbs, the Harts’ neighbors in Washington, needed no convincing. They knew the family in only one context, the desperate one created by two of their children. They saw and heard things not even trained social workers had been able to elicit from the kids.

Ten days before the crash, and about six months after Hannah’s middle-of-the-night visit, another child had arrived on the DeKalbs’ doorstep. It was Devonte, who in November 2014 had been photographed tearfully hugging a white police officer in Portland, at a protest over the police shooting of Michael Brown. Johnny Huu Nguyen, the freelancer who took the photo, sold it to the Oregonian, and from there it went viral — suddenly thrusting Devonte’s image into the limelight and casting him as a figure of unity amid the contentious national debate over police shootings. Jen initially welcomed the attention, but later resented the unflagging media pressure. Many friends said that, in part, the Harts moved from Oregon to Washington to escape it. The DeKalbs knew nothing about the viral photo, and until March had only seen Devonte on occasion. But between March 15th and 23rd, he had come to their door 11 times, asking for food. It was always at 9 a.m., after Sarah had left for work, or 9 p.m., after the rest of the family had gone to bed. They’d hear the scrape of his rubber work boots on the gravel and through their screen door they could see him running, his baggy secondhand clothing fluttering behind him.

Dana took notes. She wanted to collect as much evidence as she could before calling CPS. According to the state report, Devonte first requested tortillas, then “cooked meat,” peanut butter, apples, and bagels. He asked the DeKalbs to place these larger items in a box, in the angle of the fence between the properties. To Dana, Devonte looked “distorted,” with a frame “tinier than his head.” At first, he begged them “not to tell his mom” or call police, because he feared they would divide his siblings. By the last visit, said Dana, he had changed his mind: “Have you called yet?”

She called at 9 a.m. the next day, a Friday, with her notes at the ready. The intake worker was impatient. When Dana suggested she first describe the context, including the Hannah incident, the worker rebuffed her. “If you did that, I’d have to take down an entirely separate set of notes,” she said. Dana complied, and hung up deflated.

Two hours later, the worker called back, suddenly anxious to get the story straight. At about 5:30 p.m., a social worker arrived at the bottom of the driveway. Above, she saw the Yukon turn toward the blue house’s garage. When she made it up the hill, she knocked. She rang the doorbell twice and left her card in the door. She walked around back and knocked on the sliding glass door. “No movement was seen in the home,” says the report. Forty-five minutes after the worker left, Sarah’s rustbox Pontiac Sunfire came screeching up the driveway, and by Saturday, the Yukon, containing the children, had fled. On Monday, the social worker tried again. She didn’t know that by this point, the car was idle in the California surf. She rang and knocked, front and back, and left another card in the door.

AUGUST 2017: WOODLAND

Dana keeps returning to the morning after Hannah’s visit. She was ready to call the police, but when the entire Hart family rang their doorbell at 6:30 a.m., they blocked her impulse. She couldn’t go outside then; she’d hardly gathered herself. But when they rang again an hour later, she and Bruce went out to face them.

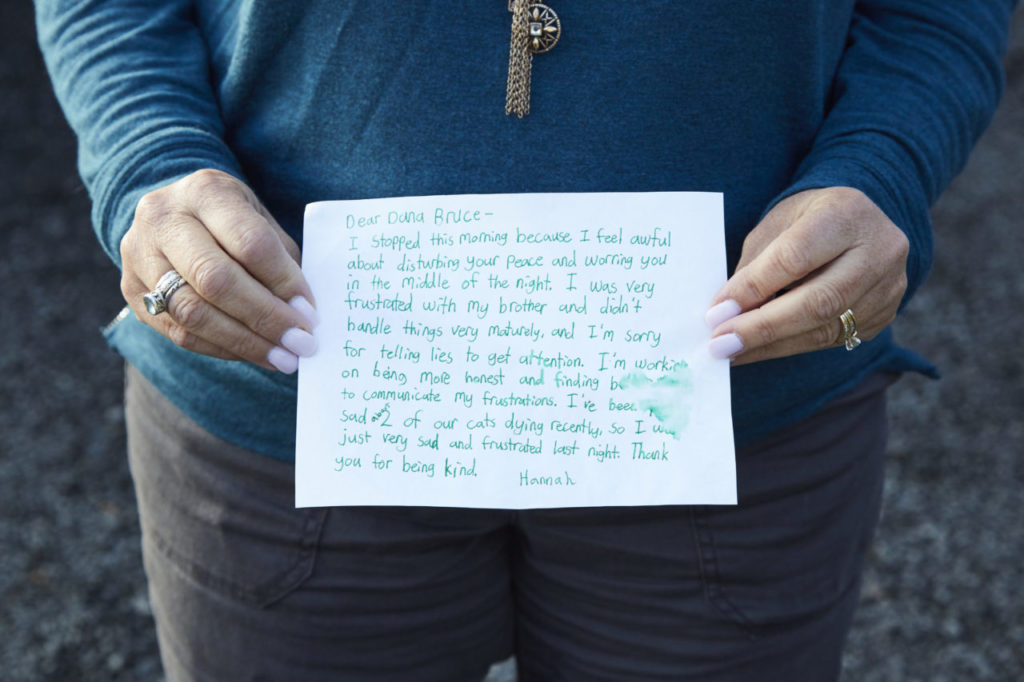

Hannah handed Dana an apology note written in green pen that said, among other things, “I’m sorry for telling lies to get attention.” Jen went through her spiel while Sarah and the kids stood silent in the background. “I will tell you, she was the master of knowing what to say,” recalled Dana. In front of all the children, Jen told them Hannah was bipolar, and that her two cats had recently died. The other kids, she said, came from unspeakable abuse, from households full of liquor, drugs, and guns. It sounded strange, but serious. It convinced Bruce and Dana to hold off. Maybe, for the first time in 21 years, their neighbors might work out.

“When they got ready to leave that morning I asked if I could speak to Hannah alone,” Dana said. “Jen said, ‘No, we do everything as a family,’ and I’m like, ugh, ‘Okay.’ I got down to [Hannah’s] level and said, ‘I just want you to know, you don’t ever have to worry about upsetting me or being a problem coming here. You are welcome in my home, no matter what time of the day, every day — you can come here. Just know that I’m here for you.’ And then I gave her a hug and said something like, ‘You just let me know.’ I wanted to tell her, ‘If this is for real, you give me a sign.’ But because they were standing right there …” Hannah stiffened as Dana hugged her. Dana stood back up, and Hannah, along with the rest of the children, followed her mothers back home.