Early dawn on Point Reyes brings another sunrise without a sun, the May fog shrouding this Saturday as winds whip up like they often do out on the peninsula.

“It’s all I’ve ever known,” says rancher Kevin Lunny. He’s talking about the wind, the light, the smell of cows, the scent of salted air off the sea — almost every detail in his life — as he drives a 4×4 into the pasture where his grandfather first set foot in 1946.

An executive at Pope and Talbot in San Francisco, Joe Lunny Sr. was a steamship man, not a farmer. But after buying a run-down dairy on the Historic G Ranch, he learned, often the hard way, from old family ranchers nearby, like the Kehoes and the Mendozas, who had worked the land long before he arrived. His son, Joe Lunny Jr., who was 17 at the time — he’s now 94 — remembers, “I came out here as greenhorn as you can be.”

Over these past few weeks, everything Kevin Lunny does, whether closing a pasture gate or fixing a fence wire or taking an evening walk down to Abbotts Lagoon with his wife Nancy — he keeps asking himself, will this be the last time?

Today, at least, one thing appears sure: This is the final cattle roundup at Lunny Ranch. The last time he’ll ever bring cows into corrals and separate them. He’s known this day might arrive sooner than later, for years now.

“But it’s still hard,” he says.

More than a decade ago, when he lost a long-shot bid to renew the federal lease inside Point Reyes National Seashore for his Drakes Bay Oyster Company, he had a premonition this day might come. After the seashore was created in 1962, with provisions for pastoral and wilderness lands, the longtime ranching families were reluctant to sell their land to the federal government, even with agreements to lease the land back.

Over the decades, those agreements came increasingly under fire from environmental groups who want more of the park turned over to wilderness and wildlife. After years of lawsuits and mediation between ranchers, environmental groups, and the National Park Service, which owns the land, the park is effectively shutting down the farm Lunny grew up on, one of a dozen set to close by next year under a voluntary buyout brokered by The Nature Conservancy.

Lunny, a frontman in many of the biggest fights over the seashore in the past decade, doesn’t want to argue over the details anymore. He held out as long as he could. Finally, his father came to him and said, “I think we have to come to a yes. I don’t want to see it kill you.”

In January, he was the last of 12 ranchers to sign the settlement, which includes a reported $30-million payout to the ranchers who agreed to leave the land forever by next spring.

Now, Lunny looks out on the pasture where his grandkids, other family, and old friends make wide sweeps on dirt bikes, horseback, and 4x4s, leading the cattle toward the corrals.

“We’ve never had this many people to gather cows in our life,” he says. “It’s really kind of everybody in the family coming together. It’s very emotional for everybody. It shows you how this place has been meaningful for generations.”

His daughter Brigid Mata, who has worked the farm since she was a child, says she originally thought maybe the last roundup should just be small and super-intimate. “But my dad said, you know, everyone has memories here. Everyone wants to be a part of it.”

On this final roundup, there are 90 mother cows, 30 bred heifers, 85 calves — many that will relocate to a pasture in southern Oregon for now. And 55 2-year-olds going to slaughter.

Over the next few hours, friends and family from as far and wide as Tennessee, Washington and all over California, will lend a hand helping sort cattle while a vet does pregnancy checks on mother cows. Mata will attach new ear tags on the cows going to Oregon, and Nancy Lunny will log every detail from the vet checks in her notebook. Eventually, empty boxes of doughnuts make way for an open-pit barbecue firing up. It feels like a family reunion, with all the hugs and back-slapping and kids running around.

“On the outside we might be laughing and smiling and carrying on, but on the inside, everyone is sad,” says Kevin Lunny.

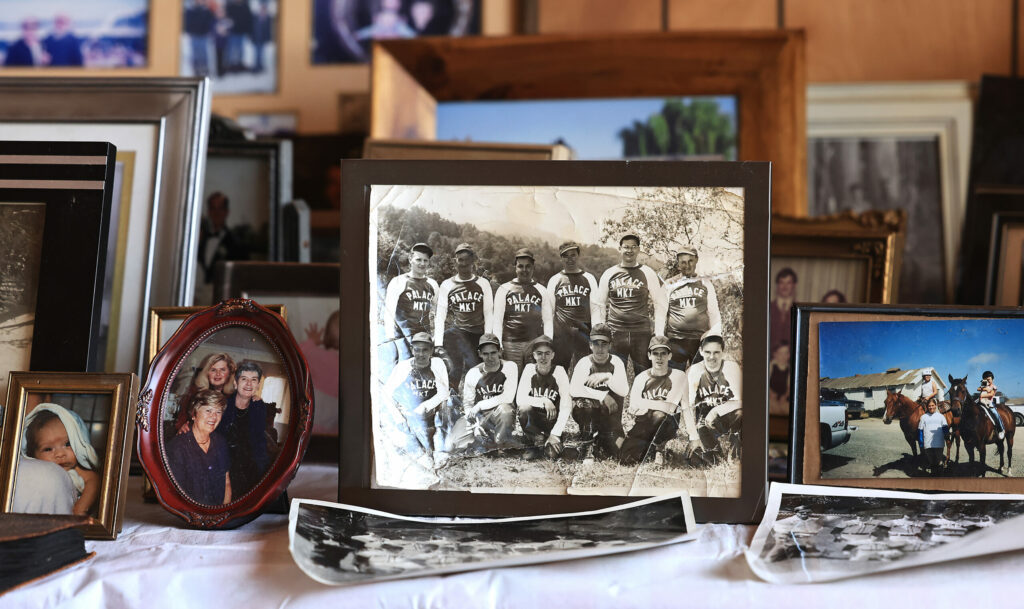

His father, Joe Lunny Jr., is taking it the hardest. He’s watching from afar, on the patio of the main house. As people park and walk up the driveway, they stop to pay their respects as if giving their condolences at a funeral. Joe leads them through a room with walls filled with family photos and deer mounts. Nearby, framed on the wall, an old Press Democrat story headline reads, “Ranching in Paradise.”

Over the years, it became anything but that.

“I thought I would die here one day,” says Joe Lunny Jr., choking back tears as he reaches out to the land with one arm.

Will he ever return to visit?

“Why would I?” he says.

By this time, in the thick of summer, Kevin and Nancy Lunny plan to be settled down in their new home on 10 acres near Auburn. His father will split time with them and his sisters, who live in Penngrove and McCloud near Mt. Shasta.

On the farm outside Auburn, there’s a pond stocked with bass and bluegill that his grandkids love to fish. Kevin Lunny thought he would have a hard time adjusting to such a quiet place, without the constant sound of the ocean and harsh winds he grew up with in Point Reyes. But a creek running through the property “that babbles year-round” has filled any void. He also kept a few cows, because he says it would be hard to live without them, and he has a barn.

Lunny has promised to stay involved in the ongoing battle over ranching in the park and help other ranchers in need. Lately, there have been rumblings that bureaucrats in Washington might reverse the deal that ended ranching in the park. If that happened, would he be interested in coming back to Point Reyes?

“In a heartbeat,” he says. “We’d do it in a second.”

But he already spent the money.

“We signed a contract,” he says. “We committed never to come back.”