Meet Miguel Crawford, husband, father, teacher, extreme velophile—dude has 15 bikes lined up neatly in his Sebastopol studio—and accidental pioneer.

It was 26 years ago that Crawford, a longtime Spanish instructor at El Molino, then Analy High School, organized his first Hopper. That’s the innocuous-sounding name for the merry sufferfests comprising the Grasshopper Adventure Series, which he founded with little to no fanfare back in 1998.

A slightly sadistic series of four to six “rideslash-races” taking place between January and summer, Crawford’s “Hoppers” have long put a premium on hard-won versatility, taking riders over pavement, dirt, gravel, distressed macadam, fire roads, old logging trails, single- track, you name it.

Ripping down Old Cazadero Road north of Guerneville, or grinding up Willow Creek outside Duncans Mills on a smorgasbord of different rigs—road bikes, mountain bikes, cyclocross bikes—those intrepid early Hopper racers didn’t look or feel especially cutting edge.

It turned out, however, that the multi-terrain adventures Crawford has been curating since the previous millennium preceded by at least a decade the rise of gravel riding and racing, a discipline that’s recently gained worldwide popularity. Grasshoppers were all about gravel—and the gravel ethos of fun and exploration— before gravel was cool.

“Gravel,” we are reminded by five-time Olympian and Hopper veteran Katerina Nash, is not to be taken too literally. That word has become shorthand, a catch-all for a mix of different terrains. A huge part of its appeal, says Nash, “is that it brings together all these athletes”— mountain bikers, roadies, members of the cyclocross tribe—“who wouldn’t otherwise meet.”

There are now hundreds of gravel racing events across the United States each year. Among the best known is Unbound Gravel, a 200-mile ordeal contested by 4,000 riders each June in the Flint Hills of Kansas. The Super Bowl of Gravel, as some refer to Unbound, has been won by several Hopper regulars, including Yuri Hauswald, Amity Rockwell, Alison Tetrick, and Ted King, who refers to the Grasshopper Series as the “OG”—the original gangster—of gravel. That tribute was validated in March of 2023 by the Gravel Cycling Hall of Fame, which included Crawford in its second class of inductees, along with Petalumans Hauswald and Tetrick—lending the Emporia, Kansas-based Hall of Fame a distinctly Sonoma flavor.

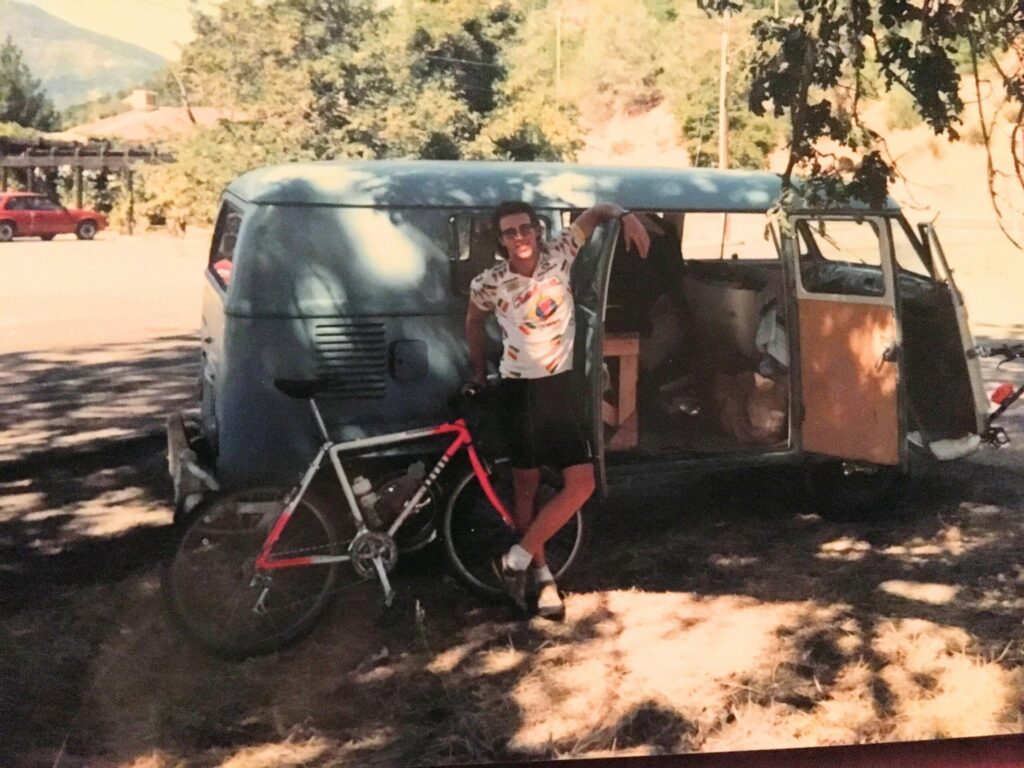

Decades before the bike industry began marketing gravel bikes, noted Crawford’s Hall of Fame presenter, Dan Hughes, “Mig and his friends were pushing their old road bikes to the limit, installing the largest tires the frames could handle and taking parts from early mountain bikes to create new frankenbikes that could handle the abuse of long mixed-terrain rides.”

The natural beauty of Crawford’s courses, coupled with the relaxed, low-fi vibe of the events, has earned the series a fiercely loyal following throughout Northern California and beyond. Hoppers tend to draw a mix of eager, über-fit amateurs and, at the pointy end of the peloton, a who’s who of pro riders, both mountain and road, seeking some hard miles to sharpen their fitness for the upcoming season.

It’s a mix that has led to some surreal moments. Crawford recalls Giro d’Italia stage winner Peter Stetina texting him from Europe to learn the results of certain Hoppers. “He’d be over in France, racing Paris–Nice or something, asking me who won Old Caz.”

But as word of the rides got out and the number of participants grew, so did attention from neighbors, including members of the Kashia Pomo rancheria. Some citizens complained to their elected officials, others to the California Coastal Commission. By 2022, the process of securing permits for Sonoma County events had become so onerous, even Kafkaesque, that Crawford made the tough, sad decision to move the bulk of the series to friendlier environs—ones outside the county where the races were born.

The one who made it happen

A three-sport athlete and member of El Molino’s Class of 1988, Miguel “Mig” Crawford became an elite bike racer following his graduation from Humboldt State. Upon returning to Sonoma County, he spent a decade, on bike and on foot, getting to know the fire roads and byways, the abandoned railroad corridors and old logging trails of west county like the creases on the palm of his hand.

Working with remote, often stunningly beautiful roads such as Sweetwater Springs, Skaggs Springs, King Ridge, Kruse Ranch, Old Caz, Willow Creek—“sounds like a greatest hits album,” notes Crawford, as he ticks them off—he devised long, looping rides that were at once spectacular and spectacularly hard.

Mig and friends would meet in the parking lot behind Occidental’s Union Hotel, where he would hand them a laminated card with a hand-drawn map of that day’s route. In those early, unsanctioned years, there was no registration, no waivers or rest stops or prizes, other than bragging rights and a bag of chips at the finish, paired with a Coke—or perhaps some other, more potent cold beverage.

Crawford would “start us on pavement, jump to dirt, connect through the backwoods to a bit of singletrack,” says old Hopper hand Geoff Kabush, a Canadian mountain biker who competed in three Olympic Games. “It was always fun to see what he was going to piece together.”

The underground feel of those early Hoppers faded as the fields grew. The registration fee edged up, from free, to $5, and then $10. By the time the legendary Ted King showed up to ride his first Grasshopper in 2011, the price of admission was up to (gasp!) $20.

“Hoppers have a different feel than a lot of the other races we do around the country. It still has that original ethos, those nuggets of camaraderie that you don’t see elsewhere.” – pro rider Ted King

The event had been described to him as a group ride, and King remembers thinking at the time, “Why do I need to pay $20 to go on a training ride?”

But he soon found himself drawn in by the fellowship and the beauty of the route. Following the punishing climb of Geysers Road outside Cloverdale, which pitches up the way Mike Campbell says he went broke in Hemingway’s “The Sun Also Rises”: “gradually and then suddenly”—riders took a left at the old Jimtown Store, finishing 3,000 vertical feet later at the terminus of Pine Flat Road.

What King remembers about that day was the fun he had, the friends he made—and the dessert awaiting them.

“There were all these cupcakes,” he recalls, 13 years later. “Really nice, artisanal cupcakes.”

“That might’ve been the best 20 bucks I ever put into my cycling career.”

As many former WorldTour pros have after him, King discovered a fulfilling second career as a “privateer”—a rider unaffiliated with a team—on the gravel racing scene. The Hoppers, he says, “have a different feel than a lot of the other races we do around the country. It still has that original ethos, those nuggets of camaraderie that you don’t see elsewhere.”

As pro mountain biker Alex Wild put it after winning the Lake Sonoma Hopper in 2022, “No one’s telling me to be here. I don’t have to put [Hoppers] on my schedule. But Mig just puts on such good events, it makes people want to ride them.”

Today we ride

Twenty-six years after Crawford and a dozen of his buddies rolled out of Occidental for the inaugural Hopper, some 600 riders straddled their bikes, chatting nervously in the parking lot at Todd Grove Park in Ukiah. It was January 27, 2024, and the group was waiting for the start of the Low Gap Hopper, a half-dirt, half-pavement, 48-mile ordeal into which Crawford crowded 6,200 feet of climbing. (For context, the first mountain stage of this summer’s Tour de France is 87 miles, with 11,617 feet of gain.)

One the coolest things about these adventures, says Chas Christiansen, an artist and pro gravel rider, is who you end up saying hello to in the parking lot or at the start. “You’re standing next to these pros—Ted King, or Levi, or Peter Stetina—guys who just rode in the Tour de France or the Giro d’Italia. It’s wild.”

Christiansen was a 20-something San Francisco bike messenger in 2010 when a friend talked him into signing up for the Old Caz Hopper – the perennial Grasshopper season opener until 2019, when a landslide prompted the county to close the road. (It has yet to reopen.)

He grabbed his vintage Miele, an Italian-style racing steed—“the only bike I had with gears,” he recalls—and headed for Occidental. Thus did he find himself later that morning battling gravity and the elements on the descent of Old Cazadero Road. Such was the steepness of one muddy section of Old Caz that Christiansen was forced to sit astride the top tube of the bike, braking Fred Flintstone-style.

“I had a foot down on each side, like a trimaran,” he recalls.

Up ahead, riders were dismounting. Why are they doing that, he wondered, until he saw the rain-swollen creek bisecting the trail. “You know it’s a good race when there’s a surprise river,” says Christiansen.

Fourteen years later he’s still racing and riding bikes for a living. Christiansen credits Grasshoppers for helping him “get comfortable being extremely uncomfortable” and “riding deep into the wilderness and being confident in my own abilities to survive and thrive.”

Standing on the far side of Austin Creek that soggy morning, photographer Paul C. Miller snapped a picture of Christiansen as the grinning bike messenger forded the stream, shlepping his vintage road bike. Behind him are two riders, one carrying a mountain bike, the other a cyclocross rig. Crawford in particular treasures that image because it captures a core Hopper tenet: There is no “right” bike.

It has long delighted him that these mixed-terrain adventures force specialists out of their comfort zones. Pure roadies merely survive the rocky, technical sections. Fat-tire folk struggle to keep up on pavement. As Hopper apostle Austin McInerny recalls, each new event prompts a fresh round of “tinkering with our bike set-ups, asking one another, ‘What tires you gonna run?’” “For me, that was the fun,” says Crawford, who for years competed in his own events, finishing first in exactly one of them. “Here’s the course, now choose what to ride. We’re all trying to get there as fast as we can. How’s that going to play out?”

Some of that mystery has been removed by the emergence of discipline-specific gravel bikes—including those made by Specialized, now the title sponsor of the series.

McInerney got his first taste of the Grasshopper series around 2006. He was immediately beguiled by the beauty of the routes, and grateful for Crawford’s willingness to share. “Surfers are all about locals only, but Mig’s attitude was, ‘No, you’re here, you’re willing to check it out, you’re part of my group.’” That day’s ride finished at the top of Willow Creek Road, “and it was a huge party up there, chips and beer and soda and people just hanging out, celebrating.”

Growing pains

Rider Austin McInerny has a background in environmental planning and has consulted extensively on natural resource management cases, including work with the U.S. Forest Service and other federal agencies “with thorny issues, a lot of it dealing with recreation and public lands management.”

For the last six years or so he’s been Crawford’s point man, working with Sonoma County to get the Hoppers permitted. For years, he said, wrangling those permits had been straightforward.

Early in 2022, when the county began consideration of McInerny’s application for a permit to run the King Ridge Supreme Hopper in March of that year, “that’s when things started to go sideways.”

As they later learned, the county was in the process of updating its system for reviewing events such as theirs. As part of that overhaul, Hopper applications were now being scrutinized by newly created Municipal Advisory Councils.

In late January of ’22, Crawford and McInerny were informed by Permit Sonoma that the King Ridge application had drawn the attention of the powerful California Coastal Commission. Concerned citizens had objected to numerous aspects of the application—in particular the Grasshoppers’ plan to use Willow Creek Road, described by one as “an environmentally fragile area within Sonoma Coast State Parks’ salmon-bearing Willow Creek watershed.”

In addition to adverse impacts sure to be suffered by the salmon, the citizen went on, area roads would be blocked by cyclists “and their friends and families cheering them on.”

With the event less than two months away, Crawford and McInerny modified the course, routing riders away from Willow Creek. For weeks, the Coastal Commission withheld its approval of the application. In a letter to the commission, McInerny expressed frustration with its ongoing “review,” pointing out that this Hopper no longer passed through the area of environmental concern.

“The event does not use any of the coastal pullouts, is outside of the busiest time of year, nor requires any road closures. The event has already received approval from California Highway Patrol and is under review by Caltrans, which issued a permit for the same event in 2019.”

“Sadly,” he wrote, “this appears to be a case of locals not wanting to share the beauty of west Sonoma County with others.”

The Grasshopper never did hear back from the Coastal Commission. But a week after McInerny sent his letter, Crawford was informed by Permit Sonoma, that, upon careful review of the code, organizers didn’t need an encroachment permit for the King Ridge Supreme, after all.

The event was on! But the drama was not over.

The course called for riders to roll west on Skaggs Springs Road, then south on Tin Barn Road. Unbeknownst to Crawford and McInerny, that intersection, and the land around it, is the Stewarts Point Rancheria of the Kashia Band of Pomo Indians.

Some of the Kashia Pomo, including tribal chairman Reno Keoni Franklin, were upset that neither the county nor representatives from the Grasshopper Adventure Series had consulted them.

“They did not require safety measures to protect the children and elders who [live] on the Rez. They did not require the riders to post safety signs or to slow down when entering the reservation,” Franklin wrote in a Facebook post the day before the ride.

Describing the event as “extremely dangerous,” that he would be “driving tomorrow to block the road and anyone participating in the race to walk their bike through reservation. I am traveling on this and could use some support.” short notice, Crawford changed the route again, shortening the course considerably to the rancheria. a follow-up email to riders, Crawford explained that he hadn’t consulted with the Kashia before this Hopper, “but neither had we prior to any of our previous events, as this was not requested by any of the county nor California permitting agencies that we had consulted. As far as we understood, both Tin Barn Road and Skaggs Springs-Stewarts Point Road are public roads which have been used legally by the public for years.”

Having spoken with chairman Franklin, Crawford continued, “I now understand the importance of contacting the Tribe, regardless of what is required by the state or the County of Sonoma. All of us, unless native to California, are visitors on this land, and this is important to remember and recognize.”

Scarred by those experiences, and considering “the uncertainty and extremely laborious requirements” of the overhauled permitting process, says McInerny, the Grasshopper hasn’t applied for any permits in Sonoma County since—with the exception of the Lake Sonoma Hopper, which is held on lands managed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which has been “fantastic to work with,” says Crawford.

“We were caught,” McInerny believes, “in the middle of an apparent turf battle between the various MACs” and Permit Sonoma staff.

While unwilling to comment specifically on the Grasshopper series, Permit Sonoma director Tennis Wick defended the county’s revamped permitting process as an improvement over the old one, describing it as more efficient, and more responsive to concerns voiced by locals.

“Conducting a community event requires engagement with and respect for that community,” he wrote in an email. “There have been multiple complaints about events impacting local residents and Tribal Partners. Now that advisory councils receive referrals on event applications, residents and businesses may comment on proposals affecting their communities.”

The Grasshopper’s brief flareup with the Kashia Pomo left “no hard feelings,” says Franklin. “We know they learned from it, and in a good way.” He describes Crawford as “a great guy” running “a great organization. They’re raising funds for good causes—causes we support, too.” (The Grasshopper series often donated money to the west county volunteer fire departments along its routes.)

“If they ever do come back, we’ll be happy to work with them.”

New chapter, new outreach

For now, however, the series that sprung up organically in Sonoma County holds all but one of its events elsewhere. In Mendocino County, Ukiah has embraced the Grasshopper series, hosting both the 2024 season-opening Low Gap Hopper in January and the Ukiah- Mendo Gravel Epic on May 11. The 89mile Huffmaster Hopper, on February 24, took place in Colusa County.

“What we’re looking for now,” says Crawford, “is to do events in communities that want us to be there, that see the benefit—that we’re bringing money in, bringing a form of recreation that’s healthy and positive.”

Yes, he is wide open to future rides in Sonoma County, but not if it means the kind administrative war of attrition the Grasshopper endured in 2022.

“It’s a shame,” says Peter Stetina, of the Hoppers exiting Sonoma County, “because they have such a rich history there.” He spoke of widespread “disgruntlement” within the county’s “cycling community”—a frustration with some leaders’ inability to see “a bigger picture” and appreciate the tourism dollars cycling can bring.

Amity Rockwell was philosophical about the migration of Grasshoppers from their original home, describing it as not so much sad as “a little bittersweet,” and, perhaps, inevitable.

Riding King Ridge and Old Caz and Willow Creek “was pretty special,” Rockwell allows. But as the number of riders in the Hoppers “doubled and tripled in size,” it became more difficult to hold the events “in a respectful manner in these really tiny places.” As it booms in popularity, the gravel scene “has undergone massive change in the last six or seven years. There are a lot of races that aren’t what they used to be. They’re something new now.”

One recent addition to Crawford’s series is a rider mentor program devised by Helena Gilbert-Snyder, a pro rider and analyst at Specialized Bicycles.

Gilbert-Snyder is passionate about correcting gender disparity in sports—which can be especially pronounced in cycling. Women make up a little over 20% of the Grasshopper fields. While that’s “above average” for gravel events, says Crawford, “I would obviously like it to go higher.”

Lining up for the Low Gap Hopper will be 20 young female riders, each paired with a seasoned female mentor.

What the job entails, said Rockwell, one of the mentors, is to “follow a junior rider around for the day, help them eat and drink and wear the right clothes.” While it might seem straightforward, “it’s a lot to take on, if you’ve never done this before.”

“When I was just getting started in my early 20s,” she recalls, the Hoppers “were a way for me to race against Olympians and WorldTour riders. And now here’s a chance for me to help a young rider who maybe has dreams of doing what I do, someday.”

She’s confident that the Hoppers will bloom wherever they’re planted. Spectacular as it is, Sonoma County has no monopoly on gorgeous Northern California scenery. And Crawford, she believes, has created “this, like, magic potion,” of elements, including the chance for pros to race hard “but not take everything so seriously,” and for up-and-coming riders to rub elbows with the pros.

“It’s just the right mix. We’re all drawn to it.”

Who loves a Hopper?

The front row of any Hopper sendoff has long bristled with world-class talent. Here are some of the big names who’ve suffered for vertical gain in the hills of western Sonoma County.

Mountain bike world champions: Chris Blevins, Kate Courtney

WorldTour road racers: Katie Hall, Ted King, Levi Leipheimer, Peter Stetina, Alison Tetrick Laurens ten Dam

Olympians: Geoff Kabush, Katerina Nash, Flavia Oliveira, Max Plaxton

Local rising stars: Luke Lamperti, Ian Lopez de San Roman, Vida Lopez de San Roman