Love or loathe them — and some might do both during the band’s lengthy concert jams, depending on the timing of everyone’s drug ingestion — it’s difficult to ignore the musical force of nature that was the Grateful Dead.

Over 30 years and through more than 2,300 shows, the band created an unparalleled musical world of wonder, inspiring a devoted community of zealots, called Deadheads, who quoted the band’s lyrics like Scripture.

Along the way, the Dead helped shape the modern music industry. The Wall of Sound speaker system and colorful light shows set a standard for live performance that still influences bands today. During the Dead’s final five years on the road, the Los Angeles Times reported, fans spent $225 million on tickets. With its own ticketing agency and merchandising savvy, the band had become one of the most commercially successful acts of all time.

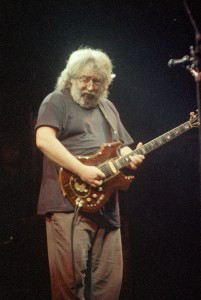

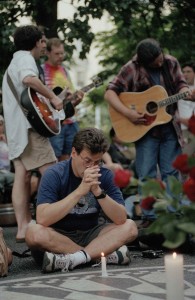

Then it all went poof. Just before dawn on Aug. 9, 1995, Dead guitarist and leader Jerry Garcia died of a heart attack in a Marin County rehab center, physically wrecked and spiritually drained. He had just turned 53. Four months later, the Dead disbanded.

This summer, the “Core Four” surviving members — guitarist and vocalist Bob Weir, bassist Phil Lesh and drummers Mickey Hart and Bill Kreutzmann — along with Phish’s Trey Anastasio filling Garcia’s shoes, put aside years of squabbling to perform two concerts in late June at Levi’s Stadium in Santa Clara and three at Soldier Field in Chicago (the site of the band’s last show in July 1995). A fall tour with singer John Mayer could also be in the works, according to music industry sources.

It’s easy to believe the long, strange trip of the band would always lead the Dead to where it is now: an American institution. But the facts suggest otherwise. The Grateful Dead might have simply been a musical sidebar to the hippie-dippie 1960s instead of a cultural phenomenon, had it not been for a rejuvenating geographic shift the band made in 1968. Saddled with debt and disillusioned by a deteriorating scene in Haight-Ashbury, the San Francisco neighborhood where the band members lived, they left a city that supported and loved them to head north across the Golden Gate Bridge and into the rolling hills of Marin and Sonoma. It was a time of restorative reinvention, resulting in a fertile period of creativity, accessibility and commercial success.

“The move gave the Dead a resting place in which to re-evaluate not just their music but also their whole lifestyle,” said Sam Cutler, who was the band’s tour manager in the early 1970s and later became their agent. “It gave them a place in which to create for themselves a new way of communal living.”

The Grateful Dead has become so much a part of the fabric of rock ’n’ roll that it’s easy to forget how revolutionary the group was. Its eclectic style blended rock, blues, folk, country, jazz, bluegrass and psychedelia into a unique whole, most memorably performed live with long chunks of musical improvisation. Concert promoter Bill Graham once said, “They’re not the best at what they do, they’re the only ones that do what they do.”

The band’s musical and cultural caravan, as indulgent as it was transcendent, was not for everyone, but the joyful communal experience of the songs and the scene was electric to fans.

“Our audience is like people who like licorice,” Garcia once famously said. “Not everybody likes licorice, but the people who like licorice really like licorice.” The Dead began performing in 1965, with several members playing together as a jug band around Palo Alto, gigging at folk clubs and coffeehouses. Sometimes they called themselves Mother McCree’s Uptown Jug Champions, other times the Warlocks.

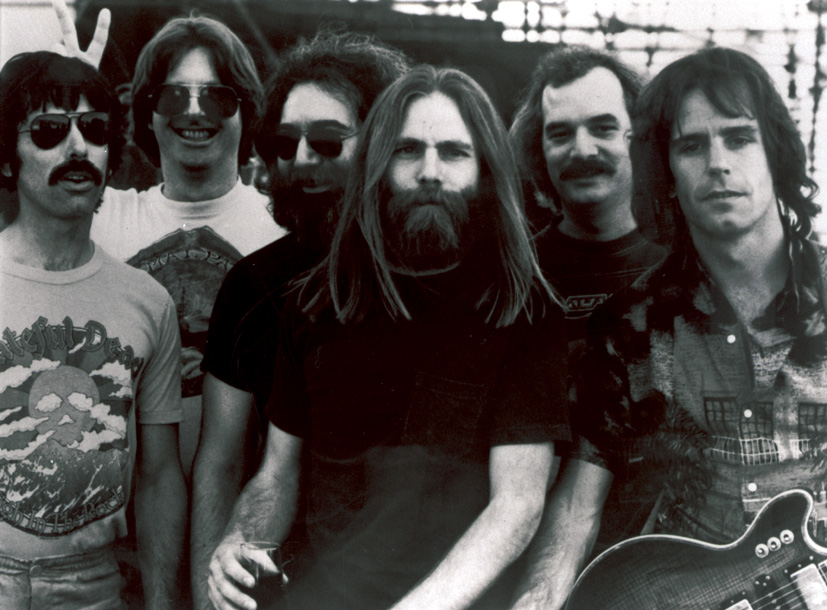

By 1966 they were the Grateful Dead and had established a base in San Francisco with a solidified lineup: Garcia, Bob Weir, Lesh, Kreutzmann and Ron “Pigpen” McKernan (keyboards, harmonica, vocals). The burgeoning San Francisco rock scene, centered in Haight-Ashbury, was creative and supportive. Jefferson Airplane members, Janis Joplin and Carlos Santana lived nearby. Colorful, mind-expanding art was everywhere. So were drugs, particularly LSD. But when a Human Be-In event in early 1967 drew an estimated 20,000 to 30,000 people to Golden Gate Park, the secret was out.

“Suddenly, every bored high school kid in America was heading to the Haight,” wrote Dennis McNally, who later served as the band’s publicist, in his book, “A Long Strange Trip: The Inside Story of the Grateful Dead.” Nasty drugs such as heroin and speed began to appear. The neighborhood got dirty and crowded.

“The Haight-Ashbury scene ended ingloriously because of over-population,” McNally wrote. “Like any ecosystem, if it becomes over- populated, it stops being healthy.”

In October 1967, the band’s communal house at 710 Ashbury St. was raided by San Francisco police, who found a pound of marijuana. Eleven people were busted, including Weir and McKernan. Originally charged with felonies, most of the defendants pled guilty to misdemeanors and paid fines of $100 to $200, according to reports in the San Francisco Chronicle. The groovy Haight-Ashbury scene of just a year earlier was gone. The band wanted to flee.

Meanwhile, a “back to the land” culture had been taking root throughout the country. Young people became disillusioned with what they felt was their parents’ soul-destroying, materialistic world, one more concerned with making war and martinis than living in peace and harmony. Alternative-living communities sprang up, including Morning Star Ranch, a counterculture commune near the apple orchards and redwood groves of Occidental and Sebastopol. The ranch began in 1966 as a social experiment, when musician Lou Gottlieb declared his 30-acre property open to all. Vanloads of people, mostly young, took him up on the offer. They set up their community, worked in the vegetable gardens, wandered around nude, shared meals, built shacks and made music.

Many traveled from the scroungy hippie hollows of San Francisco. The Grateful Dead, too, felt the pull of the land. By mid-1968, the band members had moved north, with a house on Fifth and Lincoln avenues in San Rafael as their headquarters.

“The band wanted to tap into what they felt was going to be a simpler and happier life,” said Peter Richardson, a lecturer at San Francisco State and Sonoma State University (where he recently taught a class on the history of the Grateful Dead) and author of “No Simple Highway: A Cultural History of the Grateful Dead.”

The move wasn’t the band’s first experience in the North Bay. As a teenager, Garcia lived in Cazadero in western Sonoma and attended Analy High School in Sebastopol, a lengthy daily bus ride that made the teen very unhappy, according to band histories. It was at Analy where Garcia played his first gig, plunking on the guitar as part of a five-piece combo called the Chords.

In the summer of 1966, the Dead also spent time at an unused resort camp in Lagunitas in Marin County, according to McNally, and lived briefly in a large house at the idyllic Rancho Olompali near Novato (now Olompali State Historic Park), where the band performed con- certs on the front lawn and shot the photo for the back cover of its third album, “Aoxomoxoa.”

Two years later, the musical stakes were higher.

“The Dead threw themselves into the move with a gusto,” said Cutler, noting that the band was looking for “a whole new interpre- tation of the American identity.”

The rural inspiration of Sonoma and Marin resulted in what many consider to be among the Dead’s best albums, “Workingman’s Dead” and “American Beauty,”

both recorded and released in 1970. The long psychedelic jams of the Dead’s earlier records, where numbers such as the live version of “Dark Star” could run 23 minutes, were replaced with tighter tunes, close harmonies and catchy riffs that recalled the band’s early days as a bluegrass and jug band. The songs “Friend of the Devil,” “Box of Rain,” “Uncle John’s Band,” “Truckin’’’ and “Casey Jones” sounded fresh. To the delight of the record label, Warner Bros. (to whom the Dead was $250,000 in debt), the new albums sold well, eventually going platinum.

The artwork, too, reflected the back-to-the-land ethic. The cover of “Workingman’s Dead” is sepia-toned, with a photo of the band in rugged clothes, caps and cowboys hats.

“They bought into the myth of the land and the happy yeoman,” Richardson said. “They saw some- thing utopian coming out of this.”

The Dead’s connection to Sonoma remains. Drummer Hart lives on a winding wooded road outside Occidental with his wife, Caryl, director of Sonoma County Regional Parks. In the last two decades, Hart has flourished as a solo artist and percussionist, and joined forces with Weir, Lesh and later Dead keyboardist Bruce Hornsby, as the Other Ones, playing classic Dead material as well as newer, original work. He is also the author of several books on the power of music.

“I play the drums,” Hart said on his Twitter feed. “Transformation is the object.”

Poster artist Stanley Mouse, who along with Alton Kelley created some of the most memorable Dead posters and artwork (including the famous skeleton and roses), has a studio in Sebastopol and sells his work at the Rockin Roses Art Gallery in Healdsburg. Petaluma’s Ed Perlstein photo- graphed the Dead for decades, producing classic images.

David Dodd, the collections manager for the Sonoma County Library in Santa Rosa, is one of the band’s top historians. In 1995, he founded the first website of annotated Dead lyrics (he stopped updating the site in 2007) and later created “The Grateful Dead Reader,” another examination of the band’s lyrics.

But not all the Dead’s associations with Sonoma are happy ones. Keyboardist Vince Welnick, who played with the band in the 1990s, committed suicide at his Forestville home in June 2006, after battling depression for many years.

The casual Deadhead wandering the back roads can still follow in the band’s faint footsteps. The house where the band lived at Olompali burned in an electrical fire in 1969; only the stucco walls remain. The open space and trails of the state park, however, are still gorgeous and inspiring.

The Dead’s headquarters in Marin, where the operation ran for 25 years, is now a private law practice with displays of Dead memorabilia inside. Fans can purchase soda and water from Jerry Garcia’s old Sub-Zero refrigerator at the Uncarved Block, a gem and mineral store at 112 N. Main St. in Sebastopol.

Perhaps the most vital connection to the Dead is at Terrapin Crossroads, a beautiful restaurant and concert space in San Rafael owned by Lesh, where the bass player frequently performs. Weir is known to sit in on gigs at Mill Valley’s Sweetwater Music Hall, which he helped relaunch in 2012 at a new location on Corte Madera Avenue.

For decades, the Grateful Dead has been as beloved a feature of the North Bay as the sensuous hills and rolling fog. Today, its message of love, peace, community, creativity and dance feels as essential as when the band began playing Magoo’s Pizza Parlor in Menlo Park. Fifty years later, the Dead remain as alive as ever.