The woman signing books at Barndiva in Healdsburg seemed genteel and refined as she smiled and chatted with a long line of friends and admirers.

Susan Preston had, for the time being, set her spikes aside.

That is, she’d chosen to conceal certain of her wild and sharp-edged aspects — the “spikiness,” as she recently described it to her daughter Francesca — that emerge in her art.

Since the mid-1970s, Susan and her husband, Lou Preston, have run a farm and winery in Dry Creek Valley widely beloved for its Old World feel and relaxed family vibe. Preston Farm and Winery sells superb wine, olive oil, organic produce, and artisanal food products like sourdough bread.

Less well known, but no less remarkable, are the talents and oeuvre of Susan Preston, who for decades “kind of split three ways,” in her words, dividing her energies “between children, business, and the art.”

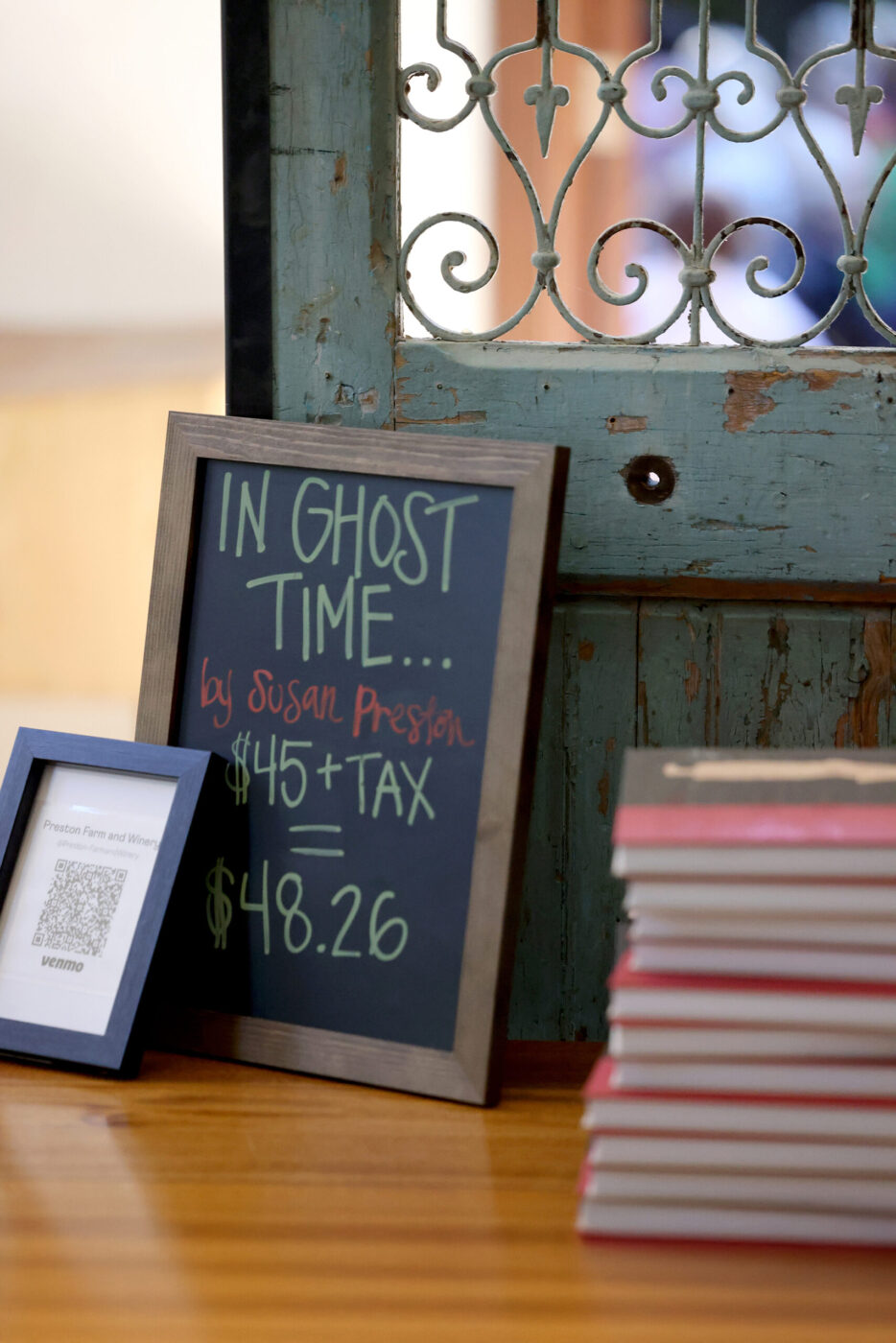

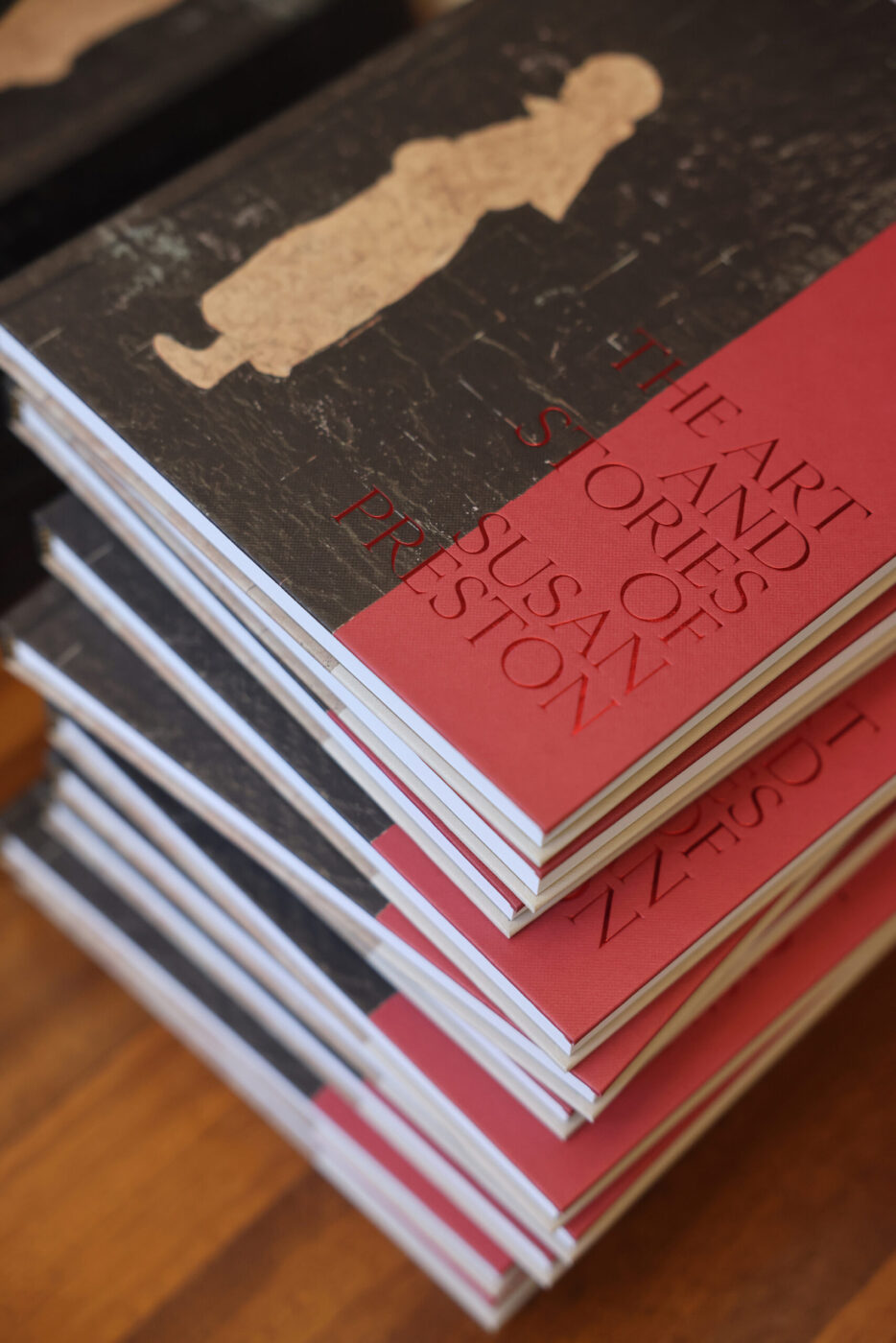

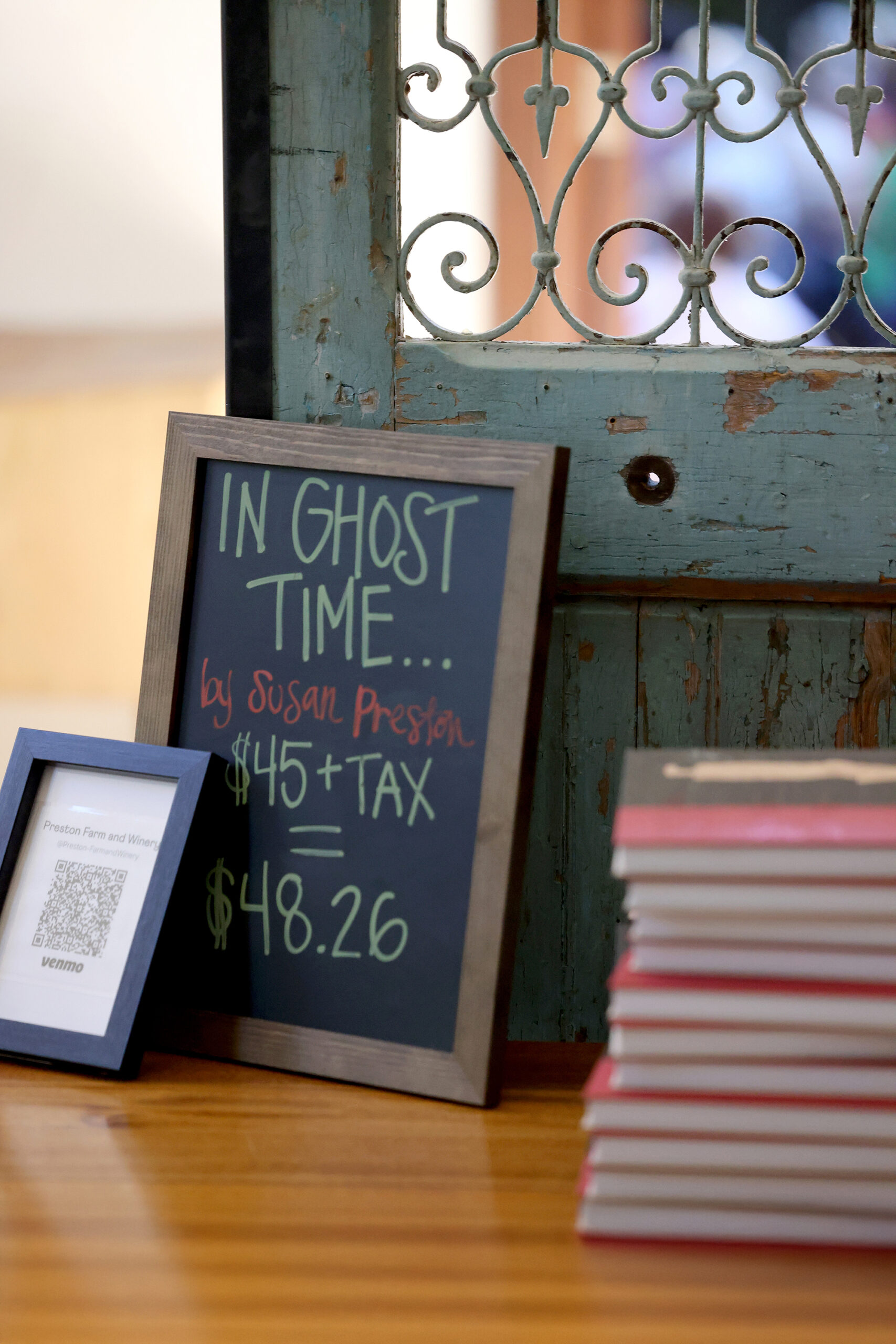

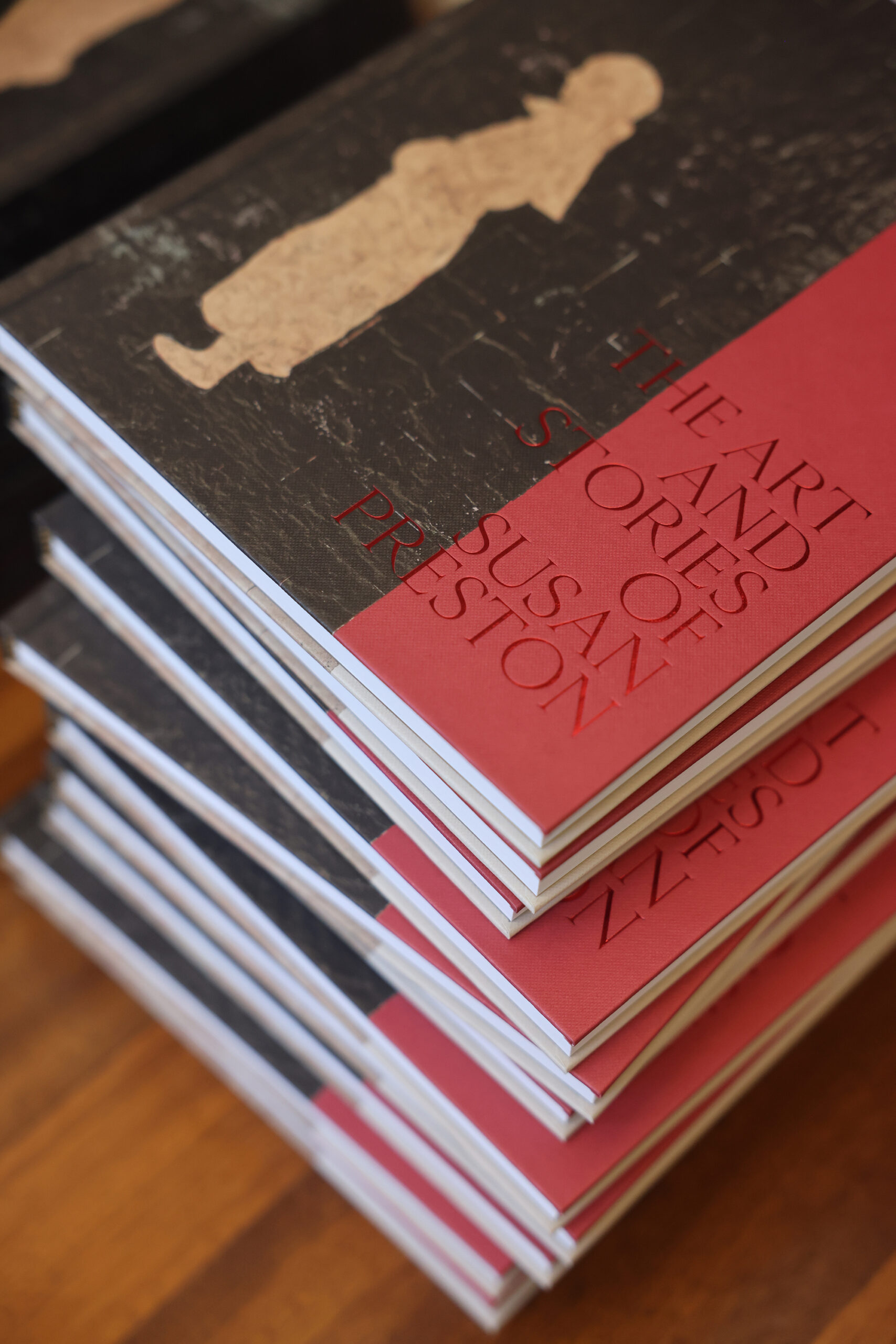

With the September release of “In Ghost Time: The Art and Stories of Susan Preston,” her profile as a creative is on the rise. While helping grow the family business and raising daughters Maggie and Francesca — both now established artists in their own right — Susan was devouring courses at Santa Rosa Junior College, then Sonoma State University, then Mills College in Oakland, where she earned her Master of Fine Arts degree in 1996.

During that time she was honing the distinctive style on display in her new monograph.

“All the teachers told me I had my own way,” Preston recalls with a smile. “They said, ‘You’re an original.’”

“She’s always been very much her own person,” said Maggie, a photo-based artist who lives and works in Berkeley, “a little unusual, a little eccentric, and not necessarily following the traditional path.”

The less traveled, often fantastical path trod by Susan Preston resulted in paintings with whimsical and occasionally sinister titles, such as “Make Noise Silently,” “Oh Noodles Please Don’t Leave Me,” “A Pimp’s Tattoo,” and “We Killed the Wrong Twin.” Preston’s collage-style works feature “mysterious and idiosyncratic images” that are “a form of visual poetry and storytelling,” wrote Stephanie Hanor, Art Museum director at Mills College.

As unconventional as Preston’s art are the materials from which it’s made: brown paper bags — the kind you get in a grocery store — bees wax, black tea, rabbit skin glue, chewing gum, olive oil, and foil.

That alchemy takes place in her stand-alone, 20-by-30-foot studio just beyond the farmhouse on their verdant 125-acre spread between Dry Creek and Pena Creek. Covering the studio’s walls are drawings cut from her notebooks. No longer strong enough to push tacks into the walls to hang those sketches, she keeps a small hammer at the ready, for that purpose.

The studio is a place of “creative chaos,” says Lou, who speaks with wonderment of his wife’s process, and “all these wild and weird things in her work.”

While she used to bury larger pieces of that brown paper in the river, Susan now covers smaller squares with earth she’s loosened in front of her studio. She checks them every so often “like you would stirring a good soup,” she explains. “When the pieces are ready, I take them inside and wash them off. Subtlety is what I’m looking for. Sometimes, I pour small streams of olive oil or tea on them.”

Thus does she summon “characters and anthropomorphic animals that challenge our perceptions about what it really means to be alive,” writes Jil Hales in an essay that appears in the book.

Hales, a close friend of Preston’s, is the founder and co-owner of Barndiva, a Michelin-recommended restaurant that doubles, by day, as an art gallery and played a prominent role in the genesis of the women’s friendship.

On the day it opened in 2004, a crowd gathered outside Barndiva for an exhibit Hales had painstakingly planned. A select group of makers had been invited to showcase their wares: wine, chocolate, cured meats, and other delectables — each complemented by a piece of art that “interpreted” the edible art.

Each, that is, except the wood-fired, heritage grain loaf baked by Lou Preston, which, 10 minutes before Barndiva’s grand opening, still had no art to accompany it.

That’s when an attractive woman with “an off-kilter swagger strode in through the main door,” Hales recalls in the Barndiva blog, “carrying a full bag of flour on her shoulder.”

Susan “proceeded to bend, slash, and pour the entire sack onto the new stone floor, just below the plinth where Lou’s ‘art’ sat beneath a spotlight.”

The flour dust had yet to settle before she left, then returned with a faded blue, spindle-backed chair she placed into the flour. It was a performance piece, Hales writes, that “fully caught the zeitgeist of the exhibit and spoke eloquently of the direction we hoped to take Barndiva.” It was also a moment that left Hales convinced: “I needed to know this woman.”

The friendship that blossomed, says Hales, has “intensified the last few years.” Preston Farm works closely with Barndiva. Susan has shown her work in its studio. In addition to being wonderful and kind, Hales notes, Preston is “forthright,” and “has an honesty about her that’s rare these days.”

It was at Hales’ urging, and with her considerable help, that Preston produced “In Ghost Time,” a collection of her paintings and sketches, along with a handful of indelible stories that shed light on her artistic process and recall her free-range, almost feral upbringing in Calaveritas, California, an abandoned Gold Rush town, which gives the book its title.

I grew up in a ghost town

And played in the remains of an old Fandango house.

Two large junk heaps and a forgotten blacksmith shop.

Sections of the town were separated by barbed wire fences.

The lines in my paintings and drawings remind me of that ragged fence.

I crave a strange and crooked simplicity.

That’s an excerpt from the prologue introducing the book’s “Stories,” which recount in Preston’s spare, evocative prose what it was like to grow up in Calaveritas without her father, who moved away when she was 3, but with an extended family that provided “both freedom and protection.”

You can take the girl out of the ghost town, but as Preston recounts in the book, the characters, shapes, and materials from Calaveritas, including “an old squeaky chair, a gold mining pan, iron trivets,” and the coiled baskets of the Miwok tribe just up the road, have long insinuated themselves into her artwork, embedded themselves in her being.

From the first day they met, said Lou Preston, whose upbringing on a dairy farm outside Healdsburg was more conventional, “I’ve been envious of her growing up with this incredible, magical independence.”

“In Ghost Time” was conceived and set in motion during the Covid-19 pandemic, a frightening, uncertain period of Preston’s life.

In chronic pain while recovering from a difficult surgery, “and with the added dimensions of Covid, the political environment, and the general unknowing,” she recalled, “something disoriented me severely.”

“I became unmoored, half in this world, half in another. No one knew quite what to do about it.”

This “time of madness,” she said, was worse for her loved ones than herself.

Hales, who described Preston’s condition as “a perfect physical and psychological storm that jumbled her signposts and signals,” came up with the idea that helped Preston find her way back to lucidity.

She encouraged her friend to assemble a monograph of her art and stories. “And for some reason,” Preston recounted, “that was the first idea that stuck, and gave me purpose.”

It took two years, but she regained her health and started painting again.

Susan Cuneo and Lou Preston went on their first date in 1973, having been introduced by Barden Stevenot, a visionary grapegrower who would later be credited with bringing the wine industry to Calaveras County. On this day, he was showing Lou a piece of land in Dry Creek Valley that held promise as a vineyard.

Stevenot brought along his friend from the Gold Rush region, Susan, who at the time was teaching at a tiny Graton elementary school.

Lou remembers Stevenot showing up “with this gorgeous and smart lady who arrived to walk around the property in the shortest skirt I’d seen in a long time.” She was also barefoot.

He was also taken with Susan’s intellectual range. “She was very literate in a way that I wasn’t.”

And so she remains, says Lou, who now finds himself wondering, “If we live long enough, can I catch up? And I’ve kind of decided I probably won’t.”

Not long after that first date, Susan brought her new beau to Calaveritas, about 5 miles east of San Andreas, “to stomp grapes in the stonewalled winery under my family home.”

On long walks to the barn late at night, she recounts in the book, “I turned cartwheels for him in the moonlight.”

A year after that first date, they were married in Calaveritas. Stevenot was Lou’s best man.

After the couple launched their business, Susan would make frequent trips to the vest-pocket post office in Geyserville, where there was always a line, she remembers.

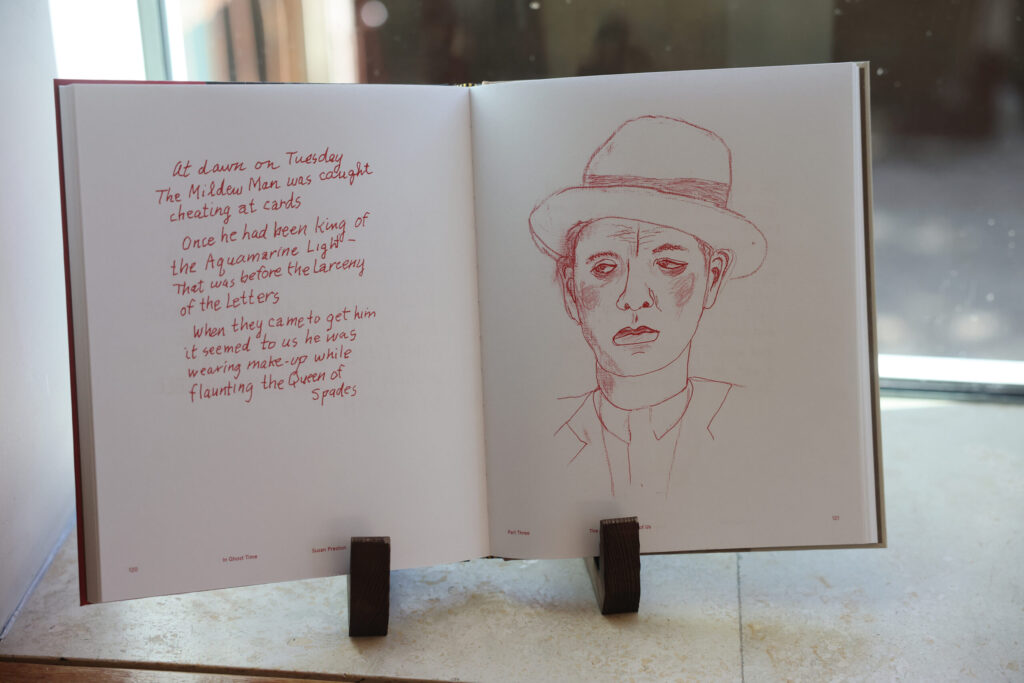

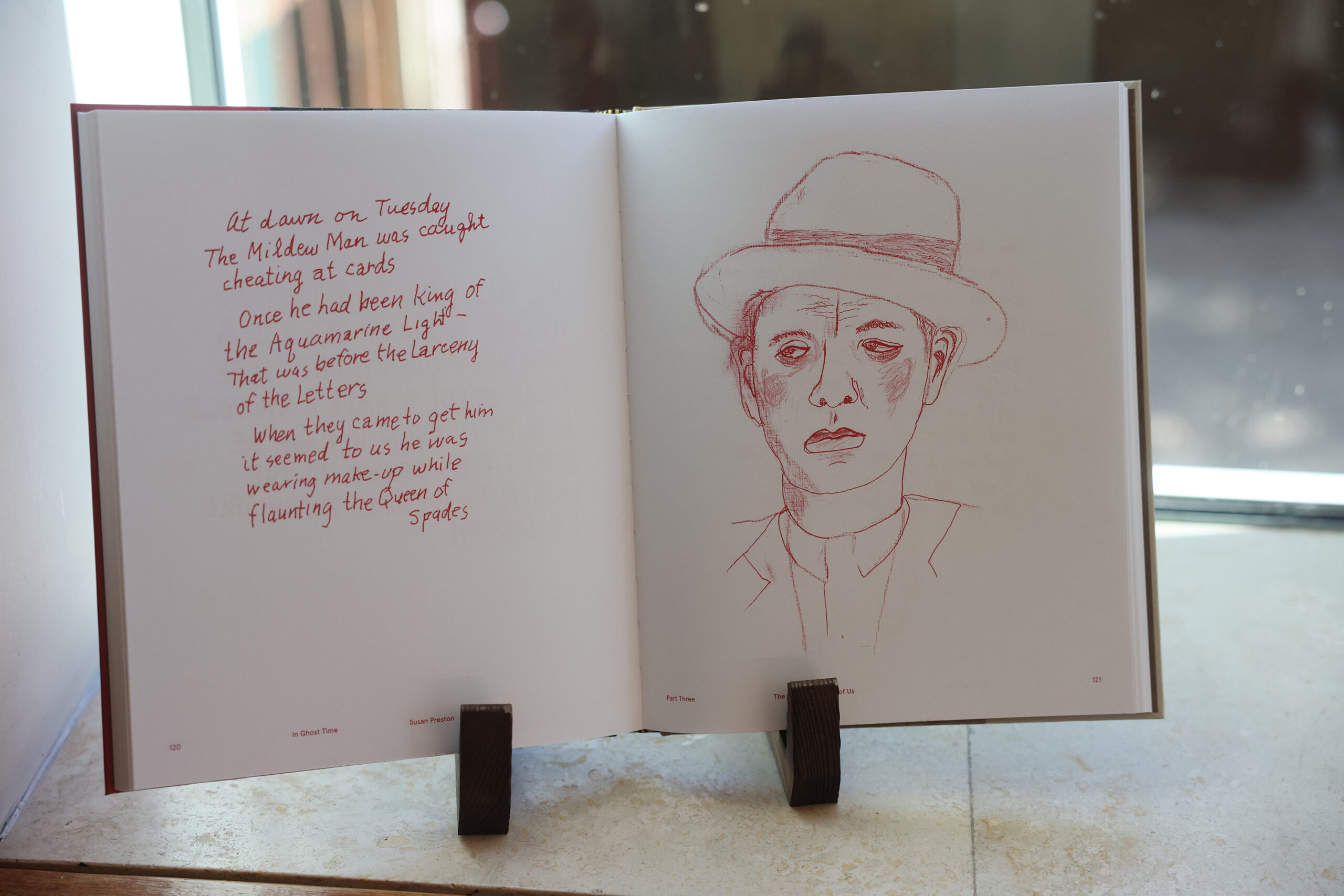

While waiting, she would turn her attention to the posters of the FBI’s “Most Wanted” fugitives. “They were a marvel,” she says. Studying their photos, admiring the cleverness of their aliases — she was especially taken with one Dwight Orlando Birdsong — Susan conjured fictitious backstories for them. Before long, she recalls, she was writing “poems and tiny stories” about them.

“In a sense some of these outlaws became my people.”

The tales of those outlaws, accompanied by her sketches, grew into a series of pieces she showed at the Southern Exposure Art Gallery in San Francisco in the early 2000s.

They also comprise “Part Three” of “In Ghost Time,” titled “The Criminal in Each of Us,” which begins with a kind of free-verse statement of her purpose:

I want to make real things, primitive, direct and concrete — like statues

Who live outside the Law.

I want to make a roomful of anarchists, who live below the earth, with

No remorse.

While raising her daughters, Preston put her life as an artist on hold. She waited until Maggie, her youngest, was in kindergarten before enrolling in art classes at the junior college.

“I would take one or two courses each semester,” recalls Susan, who was constantly checking art history books out of various libraries. Strewn about the house, those tomes were picked up and perused by Maggie and Francesca, who themselves gravitated, not surprisingly, to the arts.

So obsessed was Susan with painting, she says, that she had occasional pangs of guilt “that I wasn’t giving them enough attention” — a notion Maggie dismissed by telling her mother, “If you’d given us too much attention, we wouldn’t have been able to find our own way.”

Francesca, a poet, essayist, artist, and editor based in Petaluma, contributed “Lean In Closer,” an essay accompanying the fourth and final section of “In Ghost Time,” a crazy quilt of drawings and musings collected and curated from the dozens of journals her mother kept over nearly 40 years.

Those journals and notebooks contained “words, patterns, unanswerable questions, cross-outs, lines from poems — all dancing around and within those fabulous faces,” Francesca recalls in her essay.

The notebooks could be found throughout the Preston household, “all over the place, like turkey feathers after a dust-up. Sometimes they were left open. If I came across one, I would gaze at it like a lost sibling.”

The drawings in those notebooks, which evoke the illustrations of New Yorker cartoonist Maira Kalman, were often rough drafts, precursors of the mature works that came later. Susan’s hope is that other artists might look at the sketches “and understand how my mind works when I’m figuring out what art to do.”

To look carefully at some of those drawings, she said, is to see “exactly where my thinking was.”

In a Q&A with her mother that appeared on the website Fuji Hub in February 2025, Francesca wrote that although Susan “did normal things like pack lunches and look for ticks in our hair, she was also growing into her real life as an artist, a painter, an inward-outward thinker. By the time I was 20 she had made her way to the prestigious MFA program in painting at Mills College, under the mentorship of master Hung Liu.”

Liu, one of the first Chinese artists to establish a successful career in the United States, died in 2021 of pancreatic cancer, two months before the opening of a major exhibition of her work at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C.

A few months before her death, Liu had been planning an exhibit honoring women artists she’d mentored during her two decades at Mills. Thirteen of those former students were chosen to have their work showcased at the exhibit, Susan Preston among them.

One of the questions Francesca posed to her mother concerned a sketch gleaned from one of those journals. Beside a drawing of a gazing woman is the sentence “Put a little anger in your sugar bowl.”

Asked to explain, Susan replied, “Well, I think that as a woman I don’t want to be walked over. One of the ways we can keep that from happening is to be a little spiky. Pretend you’ve got spikes all over you. I mean, you don’t have to be that way all of the time. But like how animals can change form when they need to? Like that.”

Or like the spiked plant she mentions early in her book:

I live in a place called dry creek

Where stinging nettle grows unbidden

Along the ruffian water

Before a rain I might bury a drawing down

Under the black dirt

Near my studio door or take a painting to the river

To bury it by placing rocks on its face

When I return to collect the pieces I feel like a mother rescuing her child.