Most students at Cali Calmécac Language Academy never saw the ugly graffiti as it first appeared during the early hours of that October morning, so swift was the school’s effort to conceal it. When they arrived at the Windsor campus to start the day, outlines of the scrawled words nevertheless were still visible beneath layers of fresh paint.

Two weeks before the presidential election last fall, “Trump” and “Vote Trump” had been spray-painted overnight in black letters in dozens of places around the predominantly Latino school, where classes are taught in both English and Spanish.

And across a broad cinderblock wall at the side of campus — near where students are dropped off and picked up each day — read an even more inflammatory message: “Build the wall higher.”

It was an unsubtle reference to then-candidate Donald Trump’s pledge to barricade the nation’s border with Mexico, the familial homeland for many students on this campus and for most of the young Latino children in schools countywide.

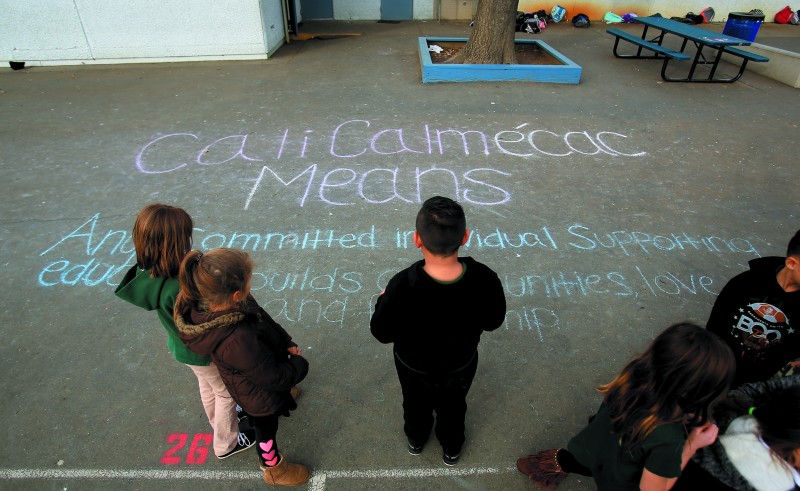

With a mere half-dozen words, vandals had made Cali Calmécac, or “Cali” as it is known locally — a public elementary school meant to celebrate cultural diversity and Latino heritage — into an another unwelcome battleground in a historically divisive presidential campaign.

-

Fourth-grader Violet Meyer runs past the outlines of graffiti that had been covered over last October on the Cali Calmécac Language Academy Campus in Windsor. (Christopher Chung)

As debates raged across the nation about immigration and border security, students as young as 5 were now learning a rallying cry used by supporters on one side to demean those of a faceless, foreign other.

“I saw a lot of really scared people that day,” eighth-grader Sophia de la Cruz, 13, recalled. “I was scared for my Cali familia that had to go through that.”

The echoes of that time, including anxiety that strikes deeply at the sense of personal security for some students, reverberated into the new year with President Trump’s first acts upon taking office. He immediately signed orders to curb immigration into the United States and to begin construction of his border wall with Mexico.

-

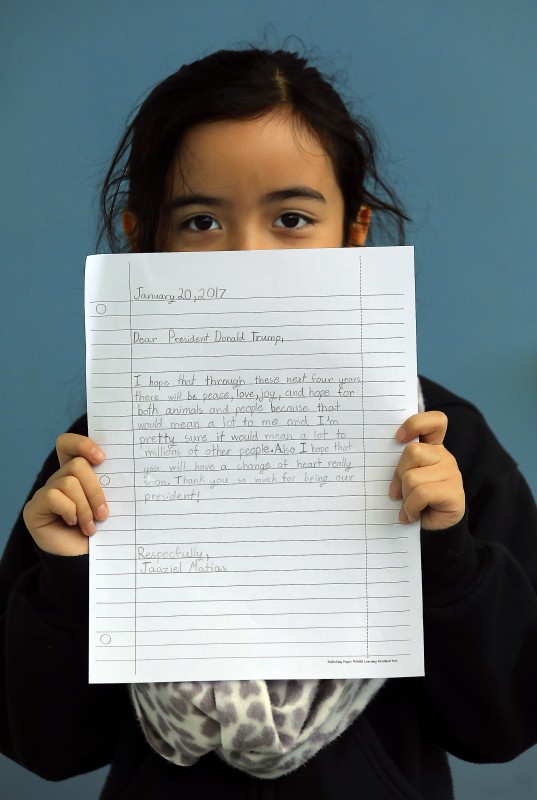

Cali Calmécac Language Academy third-grader Jaaziel Matias, 8, holds a letter she wrote to President Donald Trump on Inauguration Day. (John Burgess)

More than 70 percent of the 1,100 students at Cali, founded in 1986, are Latino, and many worry that friends and loved ones could be directly affected by Trump’s agenda.

Gustavo Zarate, a seventh-grade boy with a thin face and dark, intelligent eyes, shared the deepest dread reverberating throughout the student body.

“I feel like some kids are worried their parents will be deported,” he said. “I hear mostly little kids talk about it.”

Still, in the days and months that followed the vandals’ trespass and Trump’s shock election win over Hillary Clinton, a resilience has surfaced here that reflects the strength of the Cali community. Some believe the reaction of the larger community shows Sonoma County at its best — promoting inclusion and tolerance over bigotry and fear.

-

In the days following vandalism at Cali Calmécac Language Academy, community supporters including Christina Larkin and Susan Nelson, right, gathered outside the school as children arrived for class. (Beth Schlanker)

Two days after the graffiti was discovered, students arriving on campus were greeted by a group of their neighbors holding signs with supportive messages: “Windsor loves Cali,” “Cali Rocks” and “Have a great day at school.”

-

In response to the vandalism, community members including Susan Nelson showed their support for Cali Calmecac Language Academy before the start of class in Windsor. (Beth Schlanker)

Weeks later, a group of young, local artists created a vibrant mural to adorn the school, one they painted across the very cinderblock wall once covered by graffiti. The defiance in the gesture was clear, the mural’s imagery an homage to indigenous and Latino cultures. The faces looking back at many students were the color of their own.

“Right now, when there’s so much division and opposite views, we hope it brings back a feeling of unity and healing,” said Santa Rosa resident Emmanuel Morales, 29, one of the artists.

-

Principal Jeanne Acuña, right, hugs school librarian Gail Bland as community members show their support. (Beth Schlanker)

Like much of Sonoma County, where Clinton drew 69 percent of the vote last November, the Cali community is still bracing for life under President Trump. Apprehension exists among parents and teachers over the emerging contours of his agenda and his often dark rhetoric, steeped in a commitment to tighter controls on immigration and a crackdown on those in the country without documentation.

But as Cali looks forward, school officials and supporters say, the school has a resonant example to draw on for its response to what may come.

“I would like to believe it would happen anywhere,” said school Principal Jeanne Acuña. “I think it is a very Sonoma County kind of thing, but I think that doesn’t preclude it from happening somewhere else. I think people care about children, and they care about children feeling safe.”

Acustodian who arrived at his usual 6 a.m. start time was the first to see the graffiti on campus that Monday in October. A band teacher, whose class meets at 7 a.m., was the one who notified Acuña by phone that she needed to get to school right away.

Graffiti had turned up on the otherwise immaculate campus before, but never so visibly or widespread. This “was all over,” Acuña recalled.

“It was on the stairs. It was on garbage cans, on the lids,” she said. “It was on the walls. It was on doors. It was everywhere.”

But it wasn’t until Acuña called to inform police that she choked up, the tears forming along with “a huge lump in my throat.”

“It was such a violation and such an intentionally hateful thing to do, where small children are involved,” she said. “And that’s the part that I had the hardest time with. Why do this to children?”

The custodian, after taking photographs of the graffiti as evidence, had begun almost immediately to paint over the offending words, using supplies kept in stock for that very purpose. Maintenance personnel from the Windsor Unified School District were called to help, in hopes of erasing all signs of what had been done as quickly as possible.

Seventh-grader Leila Becnel plays in the band and so arrived early for practice that day. She saw the graffiti before it was fully covered up. It was frightening, she said, even for non-Latino students, just “knowing that someone would come onto our campus to terrorize us.”

She and her peers were immediately taken over by a desire to shield the younger kids from the graffiti.

“They shouldn’t have to worry about this, for how young they are,” said seventh-grader Meredith Gilbertson.

But “Build the wall higher” had been written across a prominent spot at school, near the cafeteria, right off the lane into campus where a large share of students and families walk or drive each day.

It was a partisan shot that jolted the school and fed anxiety that carried over into the new year.

Elias Valenzuela, 12, said he heard his younger cousin went home “telling his parents, ‘We’re going to get deported.’” Petra Montenegro and her two grandchildren, in third and fifth grade, saw the graffiti when they arrived early that day. The vandalism was deeply disturbing and confusing for the children, given their basic understanding that Trump “wants everything to be the American way.”

“The biggest question,” Montenegro said, “was, ‘Why would they do it here?’”

Even before that autumn day, many of Cali Calmécac’s students had picked up bits and pieces from talk at home or school about Trump’s campaign rhetoric, starting with that infamous opening-day missive from his Manhattan skyscraper lobby, where he reduced the mass of Mexican immigrants to rapists and drug traders.

But his talk of ramping up deportations to cover millions of undocumented immigrants and his pledge to build a border wall struck the most fear in the campus community.

From what they overheard at home, among friends and on television or online, some students came to understand that Mexicans were political targets. They asked their teachers about fellow Latinos being thrown out of the country, their families torn apart Some worried those families could be their own.

“It was targeting my people, my race, the people that I associate with,” said eighth-grader Nancy Aguirre, 14.

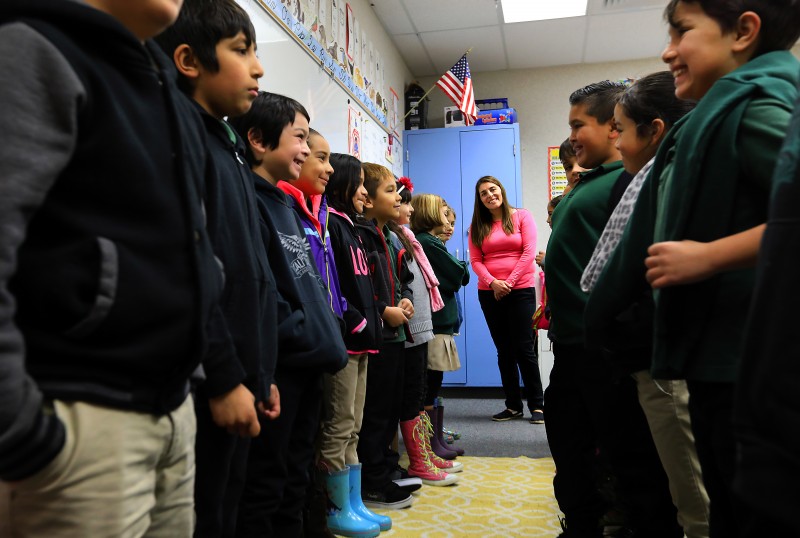

For all its progressive values, Cali does not officially embrace any strain of politics. For the administration and staff, that meant acknowledging the pre-election fears felt by many in the student body while ensuring that all, including Trump supporters, had their views heard and respected.

“We’ve talked pretty openly as a staff about how difficult it is, where you have an absolute responsibility as an educator,” Acuña said. “Your children, ideally, should never know what your political leanings are if you’re doing your job well.”

With the younger students, the goal was to curb any overwrought anxiety. In Rosa Villalpando’s class that led to deep breathing exercises, journaling and other activities meant to help students express their feelings about the campaign.

“I saw children in here talk about it and cry. And we would reassure them that there’s checks and balances, and that we don’t know yet, the campaign’s not over,” Villalpando said.

Older students who raised concerns about deportations, the border wall and other controversial topics were often instructed to take their questions to their parents or others outside the school setting, Acuña said.

“It was hard already, feeling and hearing their anxieties, and trying to make a place where they were safe and felt protected and knew they were accepted,” Villalpando said.

The graffiti felt like a repudiation of all those efforts. Teachers collecting their students that morning tried, in some cases, to route the kids around places that had been tagged. Others stood in front of painted-over areas, hoping the students wouldn’t detect what had been written.

Villalpando first learned of the incident from unsettled young students when she arrived at the playground to lead them into class. One of her pupils, Sofia Inocencio Valeria López, 8, remembered being “sad and mad” at the same time.

Some students cried, and others were filled with questions, Villalpando said.

“It hurt,” she added.

While some students managed to get to their classes without learning of the vandalism, few remained unaware for long.

Acuña was so busy attending to the situation that morning and throughout the day she didn’t send out an official notice to parents until the next day. But word still got out to the public that morning, and news of the vandalism was online before noon — prompting calls and visits from Bay Area television stations, whose reports from campus filled evening broadcasts. Media outlets across the country picked up the story over the ensuing days.

“Due to the racist overtones of the ‘Build the wall,’ and the fact that Cali was the only school affected in our district, the incident is being investigated as a hate crime by the Windsor Police Department,” Steven Jorgensen, the district superintendent, said that week in a community-wide letter to parents.

By that time, calls and messages of support were streaming into the campus. The town’s police chief posted his own message on Facebook a day after the incident calling the graffiti “offensive and racist.” “As the Chief of Police, I am also a longtime resident of the Town of Windsor,” Carlos Basurto wrote, “and I can unequivocally say that this type of behavior and thinking is not indicative of this town. This type of crime is unjustifiable and will not be accepted or tolerated in this community.”

Windsor residents and people from throughout the county were quick to rally behind the school. By Monday afternoon, messages and cards from individuals and other schools were arriving at the campus in abundance.

Students from athletics rival Windsor Middle School signed a poster declaring in both English and Spanish, “There are no walls in Windsor.”

When Cali students went to Sebastopol’s Brook Haven Middle School for a volleyball game that afternoon, supportive banners included one that said, “United against racism.”

The next day, two women stood in the rain outside campus holding signs of support, and a crowd of about 40 people appeared at the school the next morning to welcome arriving students and families with hand-painted signs and posters, many of them decorated with hearts.

“It was heart-warming to see all the kids with their smiles,” Windsor Town Councilman Bruce Okrepkie said, “and it was Pajama Day for them, so it was even cuter.”

The rally was organized on Facebook through a group created to promote acts of kindness and community service.

Organizer Vicky Royer, a former Windsor resident for whom the town’s schools remain “near and dear to my heart,” said her intent was to mount an immediate, nonpolitical show of support to counteract an unmistakable “message of hate.”

“It was basically just, ‘We’re not going to stand for hate,’” she said.

Villalpando said she still gets teary remembering how it felt to walk through the throngs of people that day with her 9-yearold daughter, a Cali student.

“Some of the signs said, ‘We are the wall’ — like ‘We are the wall of protection,’” she said.

“I think for me, that was actually a turning point,” said Beatriz Robles, a seventh-grade Spanish teacher. “We all made a point that we focused on how supportive people were, and not the opposite.”

Sonoma County’s population is about a quarter Latino, and nearly half the students in primary and secondary public schools are from Latino families. The aggression implicit in the Cali graffiti was felt far beyond the boundaries of the Windsor campus and the surrounding town. That it targeted children was unacceptable to many, “the lowest you can go,” as one Sonoma State University student put it.

Morales, one of the muralists, who works in conflict resolution with Santa Rosa City Schools, said for him, Cali Calmécac serves as an important span between cultures.

“I just feel like they’re trying to bridge that gap, the language and communication gap, and this act was something that was going counter to that, that was going to create more separatism,” Morales said.

Morales was one of the nine artists who joined with Alex Gonzalez, a Cali alumnus and member of the Santa Rosa Junior College’s Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán chapter, or MEChA. Together, they formed a group that met with Acuña and proposed a mural to celebrate the culture they felt the vandalism sought to bring down.

Over a weekend in early December, using $1,000 in contributions and additional donations from Kelly-Moore Paint, they transformed a prominent, 31-foot wall at the edge of campus into a declaration of pride and a tribute to the contributions of indigenous peoples and Latino immigrants.

“A lot of us were disgusted by it,” organizer Hernan Rai Zaragoza, 21, said of the vandalism. “But instead of just talking about it and being, like, ‘It happened,’ we decided to act upon it with love. Ultimately, in the end, you don’t fight hatred with hate. You should fight hatred with love.”

The mural recognizes the work of Latinos in the region’s vineyards; the traditional costumes and dance of Pomo Indians; and a Mesoamerican myth involving ancient deities Ixchel and Quetzalcoatl, the latter a primordial god of creation who takes the form of a feathered serpent and represents both intelligence and learning.

A swarm of butterflies symbolizes Latino migration, while a redwood and painted oaks represent nature, and an oil derrick, human degradation of the earth, said Everardo Flores, 25, another of the muralists. At the far right, two students sit at desks in a classroom with a Cali Calmécac sign, one reading a well-known history of Latin America and its struggles.

At the other end, on a separate panel, Jiovanny Soto, a Sonoma State art major, painted a stylized eagle reminiscent of the Mexican coat of arms and reflective of the school mascot.

Soto, 21, said he remembered feeling like he didn’t belong while growing up in Rohnert Park schools and sometimes spending extended periods with family in Mexico. He said he could relate to the anxiety Trump’s rhetoric engendered among Cali’s students.

“I was happy that they were at least able to look at this gesture as a sign of hope, like they’re not alone,” Soto said.

Cali eighth-grader Toby Feibusch, 14, said the message endures.

“For me, the mural now is a daily reminder that if something were to happen here to our school or our community, that the whole community not only here but around the world would be there for us,” she said.

As Cali students plunged back into their studies at the beginning of this year, anti-Trump protests spread from the nation’s capital to airports, university campuses and the streets of downtown Santa Rosa, where more than 5,000 rallied in a peaceful demonstration a day after Trump took office.

The culprits responsible for the graffiti had not been caught. But on the walls at the Windsor campus there were still a few reminders, in posters saved in the aftermath of the vandalism — “United as One,” “Love Builds Bridges” and “Let’s break through the wall of racism!!” — souvenirs of a community’s defiance.

“I feel like that’s what’s going on with the ban on Muslims,” said Nancy Aguirre, referring to the backlash after President Trump, on his eighth day in power, curbed immigration by refugees and restricted travel from seven predominantly Muslim countries.

Among Villalpando’s third-graders, Trump’s wall and pledge to deport undocumented immigrants remain key themes for classroom discussion. Many express profound sadness over the departure of Barack Obama, the only U.S. president they have ever known.

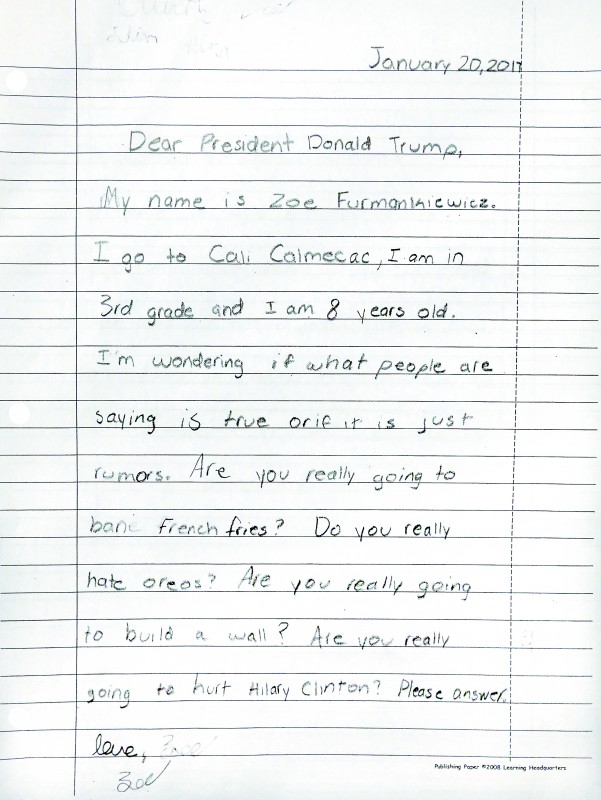

In conversation and in Inauguration Day letters penned to Trump and Obama, their thoughts reflect uncertainty, but also a surprising measure of hope and optimism.

To the outgoing president, they voice gratitude and love, penning forlorn farewells to his family and extending invitations to visit.

“My heart will always be for you,” wrote Sarahi Figueroa, 8.

“I am sad that Donald Trump is the new president,” wrote another to Obama “because half of my family is going to Mexico.”

For Trump, there are pressing questions about the border wall and other campaign vows.

“Are you really going to hurt Hillary Clinton?” Zoe Furmankiewicz wrote. “Please answer.”

Zane Arellano wrote to the president, “I hope you won’t change everything, because if you do, I and other kids will lose some friends.”

Several said they held out hope that Trump would “change his heart,” be “a good president and decide against the wall and sending Mexicans back to Mexico.”

One 8-year-old wrote:

Dear Barack Obama, I thank you for your service. I really like how positive you are and know how you feel about Donald Trump. I also hope that Donald Trump can be positive, like how you were when you were president.

Now I’m talking from my heart. If Donald Trump is going to be negative, we can’t change that. We can only be hopeful and positive. I know we can make a difference and make the world positive and a better place for everyone.

Respectfully, Cruz Mejia