Santa Rosa mountain biker Nick Northernmark uses the CamelBak Kudu 12 hydration pack on his rides through Spring Lake Regional Park and Annadel State Park.

Long-distance cyclist and emergency medical technician Michael Eidson was preparing for the Hotter’N Hell Hundred, an annual bicycle endurance race that starts in Wichita Falls, Texas, and passes through some of the most scalding terrain in the country. The year was 1988. Back then, ride organizers weren’t as diligent about hydration stations as they are today. With the relentless late-summer sun blazing overhead, Eidson was concerned that he wouldn’t be able to drink enough water to survive the 100-mile ride.

So he filled an IV bag with water and shoved it into a white tube sock, leaving the rubbery hose sticking out. He crammed the contraption into a back pocket of his bike jersey, pulled the hose over his shoulder and clamped it shut with a clothespin. Whenever he got thirsty, he released the clothespin to start the water flowing. No need to reach down for a water bottle.

At the starting line, some riders laughed at him, but it wasn’t long before cyclists and other outdoor enthusiasts were asking Eidson where they could get his homespun water system. That got him thinking about starting a business. The following year, CamelBak was born in Texas, producing hydration packs, small backpacks with reservoirs that can be filled with water.

That’s the colorful story the company offers to describe its founding. After a period of rapid growth, CamelBak was sold by Eidson in 1995 to a San Francisco firm, and relocated its headquarters to Petaluma in 1999.

The North Bay’s outdoorsy, athletic lifestyle aligned with CamelBak’s mission. Current president and CEO Sally McCoy said the company was eager to take advantage of a pool of talented prospective workers who enjoyed the outdoors. In 2008, CamelBak moved to its current location on McDowell Boulevard, a building with a bird’s-eye view of Shollenberger Park, a wetland along the Petaluma River that’s a refuge for swans, geese, avocets and ducks.

“Since we are all about water, it’s a great location,” McCoy said. “There is great bird life here, and people can go running at lunch. You can get to the mountains; you can go to the beach. It’s great for mountain biking, road biking, running, living.”

The high-ceilinged offices with exposed I-beams have floor-to-ceiling windows that allow in plenty of natural light. About 100 employees work in the environmentally friendly, LEED-certified building, their tasks including product research and design, development and testing, and sales and marketing. Manufacturing takes place at other sites in the U.S. and at company-owned factories abroad, according to CamelBak marketing manager Seth Beiden.

Its Bak to Health program provides around-the-clock snacks (Clif and Pro bars, bananas, mandarins, hummus), and there are showers for those who want to bike to work or exercise during lunch.

Beyond making its signature hydration packs, the company produces refillable, BPA-free plastic water bottles, commuter mugs and filtration pitchers. Many of the products are specific to a sport or gender. Some are for women who hike (McCoy has seen to it that CamelBak tailors products to the female form), others for men who bike. Some are for kids, others for stand-up paddlers.

The company recently expanded its line of everyday consumer products, such as the CamelBak Groove ($22), a water bottle that filters out impurities and odors. Bring the bottle empty through airport security and fill it at the gate. It does the planet a favor by reducing plastic waste from throwaway bottles.

“Our mission is to reinvent the way people hydrate and perform,” McCoy said.

One objective, she added, is to make disposable water bottles obsolete. “That’s a civilian issue and a military issue,” she said. “It takes a lot of oil and a lot of energy (to make disposable plastic bottles), and we think there’s a better way.”

While CamelBak does not provide financial information, Beiden pointed out that the CamelBak M.U.L.E. (Medium to Ultra Long Endeavors) pack has been the No. 1 hydration pack for mountain bikers since it was launched in 1996.

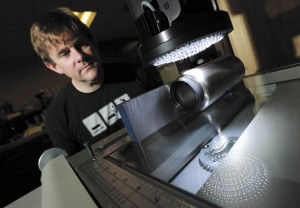

A few years ago, the company expanded its “Got Your Bak” lifetime guarantee to all parts of all of its products. To that end, a lab in Petaluma with machines that punch and prod and pull CamelBaks in myriad ways provides data about how long a product will last before it falters. A visit behind the scenes revealed a reservoir bag being pressed and twisted as a dozen bite valves were compressed between two pieces of metal to simulate adults’ and kids’ teeth biting thousands of times a day.

Much of the company’s business comes from military units of the U.S. and its allies, so reliability is essential.

Kevin Ostrom, the engineering lab manager in Petaluma, said CamelBak’s lifetime guarantee drives product design. Its glass bottles (partially wrapped in a silicone sheath) are made to survive being dropped. A prototype of an ultraviolet water-purification bottle didn’t make it to market, he said, because a glass tube inside the bottle broke too easily. It was redesigned with the UV system in the top.

CamelBak, now owned by Compass Diversified Holdings, donates to local and international water-related causes and works to reduce waste. One way is by providing water stations at music festivals, replacing an estimated 2 million plastic bottles annually, according to McCoy.

“For us, it’s about supporting people changing their habits,” she said. “We don’t preach as much as we try to support people and make it fun.”